This is a re-post of a review written several years ago. I have just re-read the book, due to its mention by a commenter looking for an excerpt. While I was not able to identify the mentioned passage, I did appreciate the quest, as it made me read extra carefully and ponder what I was reading.

I thought I might be moved to revise this older post, and I have indeed gone through it and tweaked it a very little bit, but in general I have to say that my thoughts on MacInnes’ Friends and Lovers haven’t changed this time around. If anything, I found the hero’s angst-ridden inner dialogue even less sympathetic, and the heroine’s pandering to his fixations on her acceptable behaviour even more tiresome.

This time round I was very much on the lookout for character development, to see if young semi-star-crossed lovers David and Penny appreciably matured and grew emotionally through the course of the tale. They did to a degree, but not to the point I would have liked to have seen, all things considered. We are asked by the author to sympathize throughout with the obstacles put in the place of the young lovers, and we do, but I found myself longing for an epiphany of sorts from either or both in regards to the whole “trust” factor. Penny seems in some ways to be able to better deal emotionally with the ongoing separation than David; his agitation at the thought of Penny’s contact with – gasp! – other men (even strictly socially) is rather disturbing.

David seems like he would continue to be jealous, moody and high maintenance as the years further progress; the ending scene, romantic though it was, left me fearing for this fictional couple’s longer term happiness. I wonder how Penny will respond to the feminist consciousness-raising just a few decades down the road. Will she pick up the strands of her life (the talent as an artist, for example) so easily abandoned in the throes of young passionate love when the middle-age years come and those inevitable thoughts of “what might have been” start to float to the surface of the mind?

And what will the war years bring, with the changing and expanding societally-acceptable roles of women?

Ah, well. We’ll never know. Frozen in time these two will have to remain. Interesting to speculate, though.

Friends and Lovers by Helen MacInnes ~ 1947. This edition: Little, Brown & Co., 1947. Hardcover. 367 pages.

Friends and Lovers by Helen MacInnes ~ 1947. This edition: Little, Brown & Co., 1947. Hardcover. 367 pages.

My rating: 6/10.

*****

I met this author, figuratively speaking, one long, hot teenage summer in the 1970s. With the high school library closed to me and everything else in print in the house already devoured, I was desperate for something new to read. I was half-heartedly digging through boxes of old Reader’s Digests in our sultry attic when I found a stash of hardcovers packed away in a pile of string-tied cardboard boxes, relics of my mother’s previous life in California before her marriage and relocation to the interior of British Columbia.

Mother was born in 1925, and, as a lifelong avid reader, collected as many titles as she could with her limited budget as a single “working girl”, a career which spanned almost 20 years before a late-for-the-time marriage at age 36. A browse through her collection was a snapshot of middle class bestsellers of the 1950s and 1960s, when my mother did the majority of her book buying. If I made a list of authors I’ve been introduced to through my mother’s personal library, Helen MacInnes would be solidly on there.

Best known for her suspenseful espionage thrillers set in World War II and the Cold War, Helen MacInnes also wrote several romance novels, Friends and Lovers in 1947, and Rest and Be Thankful in 1949.

Best known for her suspenseful espionage thrillers set in World War II and the Cold War, Helen MacInnes also wrote several romance novels, Friends and Lovers in 1947, and Rest and Be Thankful in 1949.

The latter title was one on my mother’s shelf, and I read it and quite enjoyed it in a mild way, so when high school resumed in September and I came across another MacInnes title in our well-stocked school library, Above Suspicion, I added it to my sign-out stack. Already a fan of Eric Ambler and John LeCarre, the political thriller immediately appealed, and Helen MacInnes was added to my mental “authors to look out for” list.

Over the years I eventually read most of MacInnes’ titles, with varying degrees of interest and enjoyment. At her best she wrote a gripping, fast-paced, suspenseful story that held my interest well; occasionally I found my attention straying. When I recently came across Friends and Lovers, I picked it up and leafed through it, trying to remember if I had previously encountered it. The title was familiar, but darned if I could remember the storyline – never a good sign! When I started reading, I knew immediately that at some point I had read the book, but I had absolutely no memory of the plot. Was this a spy novel? A romance? A few chapters in I concluded that it was a pure romance, albeit one that attempted to address some larger issues.

David Bosworth is an academically brilliant though financially struggling student entering his last year of studies at Oxford in the early 1930s. In Scotland for the summer, employed as a tutor with a wealthy family, he meets 18-year-old Penelope (Penny) Lorrimer and, rather to his dismay, falls in love at first sight. He had always thought that intellect could govern emotion; his feelings for Penny turn this long-held theory on its head, and, when it becomes apparent that Penny has been similarly smitten, a clandestine relationship ensues.

David is the sole prospective support of a troubled family. His widowed father, seriously injured in the Great War, is a helpless invalid on a small pension. His sister Margaret, who has some talent as a pianist, refuses to take on a paying job to help support her father and herself, as she feels her musical training towards a career as a concert pianist is too important to compromise.

David is the sole prospective support of a troubled family. His widowed father, seriously injured in the Great War, is a helpless invalid on a small pension. His sister Margaret, who has some talent as a pianist, refuses to take on a paying job to help support her father and herself, as she feels her musical training towards a career as a concert pianist is too important to compromise.

David has financed his own university education by attaining a series of scholarships; now with his degree in sight he is agonizing over his future and his family responsibilities. A wife and family of his own have no place in his plans, and Margaret, once she realizes David’s attraction to Penny, is openly resentful of what she sees as a threat to her own future reliance on David’s earning power. David, emotionally fastidious, refuses to entertain the notion of a relationship other than marriage with the woman of his choice; his emotional and sexual frustration are frankly and sympathetically described by MacInnes.

Penny is also faced with family opposition to the relationship. Her well-off, upper-middle-class parents are and suspicious of the designs of a financially struggling university student on their daughter. A romantic entanglement is unthought of; a marriage even more ridiculous to consider – David will obviously be in no position to support a wife of Penny’s background “in the style to which she is accustomed” for quite some years, if ever. The only reason Penny is not out-and-out forbidden to see more of David is that the idea of her seeing anything in him is so ridiculous to her parents that he is dismissed as a momentary indiscretion, not deemed worthy of further notice by Penny as well as themselves.

Penny manages to get to London to study at the Slade Art School; David visits her on his free Sundays and the relationship progresses through its many difficulties to its inevitable conclusion.

Did I like this novel? Yes, and no.

It was very much a period piece in its portrayal of the two main characters. David, to my modern-day sensibilities, is much too chauvinistic and jealous to be admirable; Penny is much too ready to conform to David’s masculine expectations. Stepping back from that knee-jerk reaction to their fictional personalities, I realize it is a bit unfair to judge them by present-day standards. As products of their environment, possibly drawn from real-life characters, (I have read that this may indeed be a semi-autobiographical story, as the two protagonists resemble MacInnes and her husband in many key ways), David and Penny do seem generally believable, if a mite annoying at times, in their stereotypical behaviour.

Their friends and families were never given as much attention in character development throughout as they could have been, a definite flaw in this novel. Things tend to fall into place a little too neatly on occasion; Penny’s throwing off of her family’s protective embrace and her establishment as a gainfully employed London working girl comes out as a bit too pat and good to be true; David is offered opportunity after wonderful opportunity and enjoys a great luxury of choice as to his own working future; one sometimes wonders what all the fuss and angst is about.

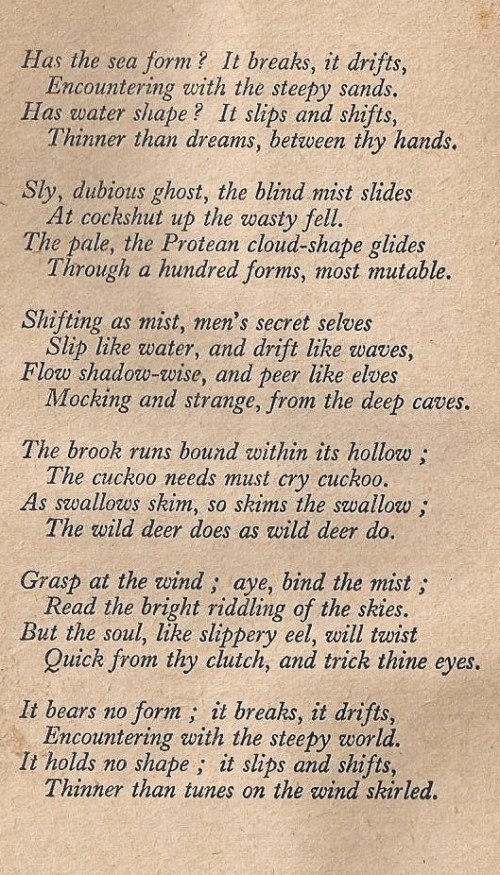

A big point in favour is the discussion of attitudes in England towards the Great War veterans. MacInnes lets her very definite political opinions (liberal, anti-fascist) show throughout. The brooding situation of the “Germany problem” is well-portrayed. The story is set in the 1930s but was written and published in the 1940s, so the author’s portrayal of the characters’ apprehensions as to their and their country’s future must certainly have been influenced by the author’s own pre-World War II experiences and thoughts. Overall an interesting glimpse into the time, written by someone who lived what she wrote about.

Absolutely honest personal opinion: One of Helen MacInnes’ weaker novels. I much prefer Rest and Be Thankful, the other of her “pure romances”, which I regularly re-read. It also discusses the after-effects of war and subsequent political attitudes, and is a stronger, more cohesive story overall with much better character development and a strong vein of humour, something I feel Friends and Lovers generally lacks. Friends and Lovers often feels forced, as if the author were rather abstracted while writing it; given the times it was written in, I will forgive her that but it does show in the final result.

Would I recommend it? Yes, with reservations. I will keep it on my shelves as a re-read, though for far in the future; no hurry! Has merit as a vintage novel, but not a favourite.

Read Full Post »

The Eyes Around Me by Gavin Black ~ 1964. This edition: Harper & Row, 1964. Hardcover. 216 pages.

The Eyes Around Me by Gavin Black ~ 1964. This edition: Harper & Row, 1964. Hardcover. 216 pages.

The Houses in Between by Howard Spring

Posted in 1950s, Century of Books - 2014, Read in 2014, tagged Century of Books 2014, Social Commentary, Spring, Howard, The Houses In Between, Vintage Fiction, War on July 23, 2014| 13 Comments »

My rating: After some deliberation, I cannot honestly give this less than a 10/10. This ambitious novel certainly has some flaws, but the overall reading experience, to me at this point in my life, was utterly satisfying.

A week or so ago I posted a quick teaser about this novel, and I am happy to report that it more than fulfilled its promise. It took me quite a long time to work my way through it, both because of general busy-ness in my real life, and my reluctance to rush through the book. Fine print, thin pages, and rather intense content made it crucial to be able to really concentrate; it was not a particularly “easy” read, though I did find it completely engaging.

On her third birthday, May 1, 1851, young Sarah Rainborough visits the newly-opened Crystal Palace in London, and the experience so impresses her that it becomes her earliest vivid memory, to be referenced throughout the rest of her long life.

I am not going to share many more plot details than this, as the story was most rewarding to me as I read with no prior knowledge as to where it was all going to go, and there were some surprising developments.

Written in the first person as an autobiography, with Sarah starting to record her life in her later years and the tone very much one of “looking back”, there are of course many references to future events, interweaving Sarah’s past and present and going off into short tangents here and there. Sarah’s fictional life covers ninety-nine years of a history-rich century, and though as a member of the upper middle class our narrator is cushioned from the harshest realities of her time, she is fully aware – at least in retrospect – of what is going on all around her.

The strongest part of the book to my mind was the portion regarding the Great War. The author, using his character’s voice, is bitterly sincere in condemnation of the brutal destruction of an entire generation of the best and brightest of England’s – and Europe’s – young men, and the impact of their loss on the structure of society as a whole, and on the families and individuals left behind.

Part social commentary and part good old-fashioned family drama – Sarah’s personal life and the lives of her family members are chock full of incident, some spilling over into positive melodrama – the book is by and large very well paced and beautifully balanced between fiction and history.

Here is the author’s foreword, which tells of his intentions. I must say that I thought he pulled it off rather well.

Howard Spring made a commendably good job of voicing his narrator; occasionally it felt a tiny bit forced, but in general he drew me in and kept me engaged. The latter chapters, covering Sarah’s extreme old age, were particularly believable, as the narrator is shown to be letting herself go a bit, both in her recording of the current phase of her life, and in her relationships to the people around her, as she deliberately eliminates strong emotional feelings regarding her descendants and looks more and more inward, preserving her energies for herself.

An author whom I shall be exploring in the future. I very much liked what he did here, though no doubt some of the appeal of this book is in that it describes the long life of a rather ordinary woman, and I am myself in a reflective mood regarding the life of my own mother, who died just over a month ago at the venerable age of eighty-nine, a decade less than our fictional Sarah’s, but still impressive, when one considers the societal changes that occurred in her (my mother’s) life as well.

Well done.

For more reviews:

The Goodreads page has several succinct and accurate reviews by readers.

Reading 1900-1950 has a detailed review, with excerpts, as well as links to reviews of several other of the author’s novels.

Read Full Post »