The Road Past Altamont by Gabrielle Roy ~ 1966. Published in French as La Route d’Altamont. This edition: New Canadian Library, 1976. Translated and with an Introduction by Joyce Marshall. Paperback. ISBN: 0-7710-9229-6. 146 pages.

The Road Past Altamont by Gabrielle Roy ~ 1966. Published in French as La Route d’Altamont. This edition: New Canadian Library, 1976. Translated and with an Introduction by Joyce Marshall. Paperback. ISBN: 0-7710-9229-6. 146 pages.

My rating: 10/10.

It has been a while since I read much of Gabrielle Roy, but my recent discovery of Enchanted Summer reminded me of how much I enjoyed her writing in summers long past. For to me Gabrielle Roy is best read in summer, on those sunny days that invariably follow the solstice; something about her delicacy of expression and lightness of touch belongs to the stillness of summer afternoons, and to times of repose in green shade.

I came to The Road Past Altamont with high hopes; they were met in full. And, too, very personal feelings were stirred by these anecdotes of generations of (mostly) women, and their ways of dealing with the passing of time and the separation of the generations in a very real sense, as my own almost-grown children are poised for their journeys into the wider world, and my own elderly mother for her withdrawal from it.

The Road Past Altamont is an assemblage of four connected, chronologically ordered short stories, or, rather, vignettes. The central character is Christine, youngest daughter of a Manitoban francophone family. Readers of Gabrielle Roy will remember Christine from Street of Riches, in which she is the narrator of a similar collection of vignettes. Christine is an autobiographical character, based on Gabrielle Roy, and Christine’s memories and responses are, one must therefore speculate, Gabrielle’s.

In the first story in The Road Past Altamont, My Almighty Grandmother, six-year-old Christine is sent, at her grandmother’s request, to visit for part of the summer in a rural Manitoba village. Christine is at first sulky and reluctant, informing Grandmother upon arrival that, “I’m going to be bored here…I’m sure of it. It’s written in the sky.” Grandmother takes up the challenge at once, and Christine, though she does frequently succumb to the lassitude of hot summer afternoons, ends up with a strong love and admiration for her still-capable grandmother, who is slowly being relegated to the status of “poor old Mémère” by the rest of her large family of descendants. To Christine’s amazed delight, Grandmother makes her a doll from odds and ends, scraps of cloth, leather and yarn; even weaving a tiny hat. While the two work, Grandmother muses on the ironies of growing old.

“That is what life is, if you want to know… a mountain made of housework. It’s a good thing you don’t see it at the outset; if you did you mightn’t risk it, you’d balk. But the mountain only shows itself as you climb it. Not only that, no matter how much housework you do in your life, just as much remains for those who come after you. Life is work that’s never finished. And in spite of that, when you’re shoved into a corner to rest, not knowing what to do with your ten fingers, do you know what happens? Well, you’re bored to death; you may even miss the housework. Can you make anything out of that?”

… She grumbled on so that I dozed, leaning against her knees, my doll in my arms, and saw my grandmother storm into Paradise with a great many things to complain about. In my dream God the Father, with his great beard and stern expression, yielded his place to Grandmother, with her keen, shrewd, far-seeing eyes. From now on it would be she, seated in the clouds, who would take care of the world, set up wise and just laws. Now all would be well for the poor people on earth.

For a long time I was haunted by the idea that it could not possibly be a man who made the world. But perhaps an old woman with extremely capable hands.

In The Old Man and the Child, Christine is a few years older. Grandmother has died, and Christine’s deep unhappiness about losing her is salved by her new acquaintance with an elderly neighbour several streets over from her own. Monsieur Sainte-Hilaire sees Christine fall while walking gingerly on her newest passion, a pair of stilts; he picks her up and dusts her off and sends her on her way buoyed by his admiration for her tenacity and agility. Christine basks in his admiration; the two become close friends. As the hot, hot summer proceeds – one of the hottest and driest in living memory – Monsieur Saint-Hilaire and Christine hatch a plan together, a visit to the great inland ocean, Lake Winnipeg, which Christine has never seen, and which the old man yearns for, having spent much time beside it in his long-ago youth. Against her better judgement, Christine’s mother gives permission for the long day’s excursion.

At length the old man asked me, “Are you happy?”

I was undoubtedly happier than I had ever been before, but, as if it were too great, this unknown joy held me in a state of intense astonishment. I learned later on, of course, that this is the very essence of joy, this astonished delight, this sense of revelation at once so simple, so natural, and yet so great that one doesn’t quite know what to say of it, except, “Ah, so this is it.”

All my preparations had been useless; everything surpassed my expectations, this great sky, half cloudy and half sunlit, this incredible crescent of beach, the water, above all its boundless expanse, which to my land-dweller’s eyes, accustomed to parched horizons, must have seemed somewhat wasteful, trained as we were to hoard water. I could not get over it. Have I, moreover, ever got over it? Does one ever, fundamentally, get over a great lake?

In The Move, Christine is eleven, and has made unlikely friends with Florence, whose father, among his other odd jobs, often works as a mover, driving a team of horses and a huge cart, trundling the sad possessions of the poor of the city from one dismal home to another. At this time the team of horses is itself becoming an anomaly, as technology has largely replaced them with the internal combustion engine. Christine is fascinated by concept of moving house; she has never personally experienced it, other than the temporary removals of holidays and such.

To take one’s furniture and belongings, to abandon a place, close a door behind one forever, say good-by to a neighbourhood, this was an adventure of which I knew nothing; and it was probably the sheer force of my efforts to picture it to myself that made it seem so daring, heroic and exalted in my eyes.

“Aren’t we ever going to move?” I used to ask Maman.

“I certainly hope not,” she would say. “By the grace of God and the long patience of your father, we are solidly established at last. I only hope it is forever.”

She told me that to her no sight in the world could be more heartbreaking, more poignant even, than a house moving.

“For a while,” she said, “it’s as if you were related to the nomads, those poor souls who slip along the surface of existence, putting their roots down nowhere. You no longer have a roof over your head. Yes indeed, for a few hours at least, it’s as if you were drifting on the stream of life.”

Poor Mother! Her objections and comparisons only strengthened my strange hankering. To drift on the stream of life! To be like the nomads! To wander through the world! There was nothing in any of this that did not seem to me like complete felicity.

Since I myself could not move, I wished to be present at someone else’s moving and see what it was all about…

Christine sneaks away early one morning to accompany Florence and her father on one of their jobs; she comes home devastated; it is not the joyful experience she had imagined. Mourning to her mother that the view from the seat of the wagon is not as she had imagined it to be, Maman realizes with dismay that Christine is one of the yearning ones; one who will always be looking for new horizons…

“You too then!” she said. “You too will have the family disease, departure sickness. What a calamity!”

Then, hiding my face against her breast, she began to croon me a sort of song, without melody and almost without words.

“Poor you,” she intoned. “Ah, poor you! What is to become of you!”

It is so much more heart-rending to be the one left than the one leaving, and Maman struggles mightily with the pain of desertion when Christine, now a young woman, breaks it to her that she is about to embark on her long-desired travels, to go to Europe, to explore the greater world. The Road Past Altamont, the last story in the book, is the most delicately poignant, as Christine and Maman drive together across the prairie to visit relatives on the outskirts of the Pembina Hills, the only “mountains” in southern Manitoba. Maman yearns for the hills, but as there is no road into them, she fears she will never walk among them, so when Christine inadvertently take a wrong turn, “just past the village of Altamont”, and ends up in the gentle mountains, her mother’s joy is overwhelming. However, on a return trip, they cannot find the road again, and soon Christine will be gone…

Maman was perhaps close to admitting that she felt herself to be too old to lose me, but there is a time when one can bear to see one’s children go away but after that it is truly as if the last rag of youth were being taken away from us and all the lamps put out. She was too proud to hold me at this price. But how insensitive my lack of assurance made me. I wanted my mother to let me go with a light heart and predict nothing but happy things for me…

Christine goes away, accompanied in her memory by all of the women in her family that came before her, and her mother encourages her in her travels, sharing her own small stories and dreamed-of destinations, which Christine has moved so far beyond. It is only in later years, looking back on that drive together towards the elusive hills, that Christine realizes how gracious her mother was in hiding her own deep pain and in opening her arms wide to let her youngest daughter freely go, unrebuked and encouraged on her way.

*****

A lovely book, and, for me, a timely one. The sensitivity of her observations is surely what has made Gabrielle Roy such a beloved author; her visions hold a lasting appeal, and something of comfort, too, across our varied experiences and all the years between our times.

Read Full Post »

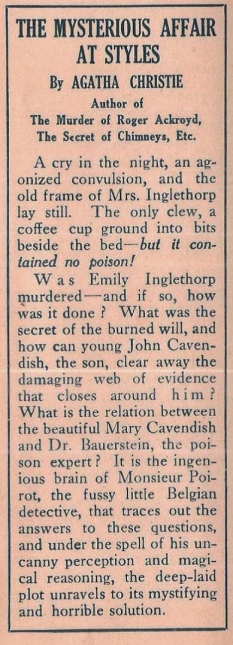

The Mysterious Affair at Styles by Agatha Christie ~ 1920. This edition: Grosset & Dunlap, 1927. Fourth printing. Hardcover. 296 pages.

The Mysterious Affair at Styles by Agatha Christie ~ 1920. This edition: Grosset & Dunlap, 1927. Fourth printing. Hardcover. 296 pages.

Review: My Discovery of America by Farley Mowat

Posted in 1980s, Canadian Book Challenge #7, Read in 2013, tagged Biography, Canadian, Canadian Book Challenge 7, Political Rant, Social Commentary on July 30, 2013| Leave a Comment »

My rating: 6/10.

High marks for tackling this topic with such eloquent vigour, tweaked downward for the increasingly bombastic posturings of the author, which led me to a sneaking small sympathy for his unwary opponents. As I read I could envision the froth forming at the Mowat’s mouth, perhaps dribbling down his legendary beard, too, as he raved on and on and on. (The conciliatory last chapter, where he thanks his many supporters in the U.S.A., did seem a bit calmer, and appropriately sincere.)

Oh – adding another point back on for that first chapter, in which Mowat describes his airport encounter with the Forces of American Evil, a.k.a. the INS: Immigration and Naturalization Services of the United States of America. It was a truly funny piece of writing, and for this I will forgive the annoyance Mowat so often inspires in me by his ego-driven blusterings, which, in this instance, had plenty of justification.

Okay, here’s the story. On April 23, 1985, as Mowat was setting out on a trip to the West Coast of the U.S.A. on a joint lecture/promotion tour for his just-released Sea of Slaughter (a passionate indictment of the human-caused ecological devastation of the Atlantic shores of North America), he was escorted off the plane as it sat on the tarmac, and notified that he was persona non grata in the U.S.A. Forever and for always. And no, we can’t tell you why, sir. Just go away now, sir.

Mowat storms out of the airport terminal and into the arms of his publisher, where he is met with a shared indignation exceeding even his own. “This is war!” (or words to that effect) cries Jack McClelland, and a press deluge begins, spurred on by the very recent “Irish Eyes are Smiling” Reagan-Mulroney love-fest, and assurances by both leaders that the U.S.A. and Canada are dear, dear friends.

Why does the mighty United States feel that wolf-, whale- and generally nature-loving Mr. Mowat is a security threat? And why do the words “Commie sympathiser” keep coming up, though no one will let Mowat or anyone else take a look at his secret file, the one that led to its abrupt barring from the neighbouring country?

It seems that there is a McCarthy-era law on the books, the McCarran–Walter Act, which allows such arbitrary barring on the most microscopic past “offenses”, such as visiting the USSR (which Mowat had done some fifteen years earlier, to research his book Sibir), and – oh! that little incident in which Mr. Mowat reported a desire to shoot his .22 rifle at U.S. Air Force planes carrying (possibly) atomic warheads across Newfoundland air space…

125 pages later, not much has changed, except that Mowat is offered a “parole” to allow him a one-time entry into the U.S.A., which he scornfully turns down, “parole” implying some sort of wrong-doing.

In this post-9/11time of ever more stringent border examinations, and many more arbitrary black-listings for undisclosed reasons – “security risk” being the handy catch-all phrase – Mowat’s prior experience sounds sadly like something we’ve all heard before.

Mowat’s horrified indignation echoes so many others; his response was the one every wronged citizen dreams of pulling off. Lucky for Mr. Mowat that his celebrity and many connections allowed him to speak out so vibrantly without losing his livelihood or credibility, a real problem for so many others in the same position, as Mowat points out, and which is one of the reasons he puts forward for his strident rebuttal to his black-list barring.

An interesting read, and with chilling parallels to the situation today between the countries on both sides of the world’s longest – but for how much longer? – undefended border. The razor wire, both literal and figurative, is persistently going up.

Here, FYI, is a very partial list, courtesy Wikipedia and therefore including the related links, of some of the public figures joining Farley Mowat on the McCarran-Walter exclusion list, before its amendment (but not its dismantlement) in 1990:

Read Full Post »