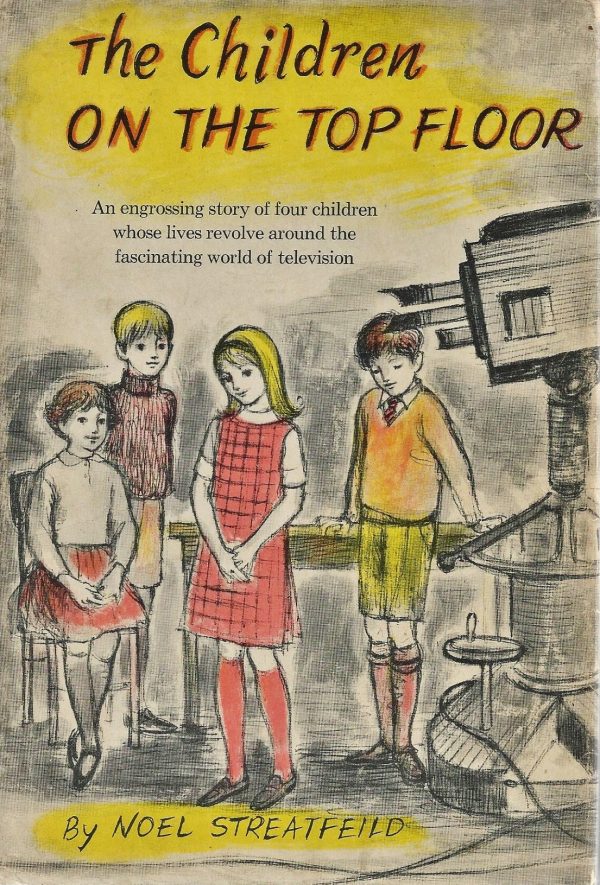

The Family on the Top Floor by Noel Streatfeild ~ 1964. This edition: Random House, 1965. Hardcover. 248 pages.

Goodness, look at that calendar! Almost March. Well, I’ve been getting in a respectable amount of reading time – it’s still dark in the evenings and we are still snowbound, so outside garden work hasn’t ramped up yet – and the pile of books-I-want-to-talk-about is really stacking up. I likely won’t get to them all, unless I whip off a slew of 100-word micro-posts (now there’s a tempting thought!) but hey, we do what we can.

Suspend your disbelief – and maybe your expectation of quality storytelling – when you crack the pages of this deservedly obscure Streatfeild juvenile.

Suspend your disbelief – and maybe your expectation of quality storytelling – when you crack the pages of this deservedly obscure Streatfeild juvenile.

Malcolm Master is a stunningly successful television personality. The whole of England hangs on his every word, and of course his cleverly produced Christmas Eve broadcast is something extra special. Malcolm stares the camera right in the eye that fateful night, and declares in a voice quivering with apparent sincerity,”Christmas is not Christmas without children. You cannot guess what this old bachelor would give to wake tomorrow morning to the squeals of delighted children opening their stockings.”

Be careful what you ask for, Mister Master. Because guess what appears on his doorstep bright and early Christmas morning, just in time for the milkman to carry inside?

Yup. Four wee babies. Two boys, two girls, all of approximately the same age, and each apparently well fed and cared for and accompanied by anonymous and sadly inane Christmas cards from four different mothers.

I was quite enthralled by this development, thinking to myself, “Aha! Children of our hero’s indiscretions, a la The Whicharts!” (For those unfamiliar with that odd little tale, it’s essentially Ballet Shoes for grownups, with the children landed on the doorstep of their father being the offspring of his ex-lovers.)

Well, this idea was soon put to rest, as these random babies do not get any backstory at all, and no one ever seems to inquire about their origins, and they are immediately absorbed into the household which is conveniently staffed with an assortment of “cottage loaf shaped” mother figures who glom on to the babies and whisk them away to be raised in seclusion on the top floor of Malcolm Master’s stately home.

The children are named after nursery rhyme characters and are raised in a certain degree of luxury, because they soon are introduced to the starstruck nation as Malcolm Master’s “quads”, stars of numerous television commercials advertising a wide range of products with attached sponsorship deals which clothe and feed and house the children with the very products they are used in touting.

Malcolm himself really doesn’t have much to do with the children – they’re very much in the background as he goes about whatever it is he does to keep his own star shining bright, so when disaster strikes in the form of a heart attack brought on by overwork, and a subsequent sea journey to recuperate, the children and their well-meaning pseudo-mothers are left to get on with things as best they can. For Malcolm has inexplicably not had the foresight to arrange for the care and feeding of his many human responsibilities, and money starts to get tight. Oh, dear, what shall we do? Who will care for the children now that the Master money has (apparently) run out? They may have to go to an ORPHANAGE!!!

Um, okay. I can think of quite a few options, but hey! – most of them would be quite sensible and not very exciting, plot wise.

This is essentially the hackneyed Ballet Shoes formula, first trotted out to great success in 1936, transposed to 1964, with the Wonderful World of Television and the Master’s children’s eventual preoccupations and probable future careers – actress, costume designer, cameraman, film engineer – taking the place of the Fossils’ performing arts focus.

There’s so much more I could say, meanly deconstructing this flat little fairy tale episode by episode, but I will leave us right there. A peek at the Goodreads page shows quite a few readers retaining very fond memories of this one, and that’s fair enough. I came to reading Noel Streatfeild as an adult, so there is no childhood nostalgia to temper my reactions to the more far-fetched of her literary efforts.

Her best books – of which there are a respectable number – are very good indeed. Her middle-of-the-pack efforts – very readable in a “light entertainment” sort of way. And some never really get off the ground, and for me this was one of those.

The Children on the Top Floor starts out with oodles of promise, and it could have been charming and quite funny, but unfortunately it soon fizzled out. With 248 pages to work with, it’s not as if there were space constraints, but Streatfeild must have been jaded when she picked up her pencil on this one.

To be fair, an awful lot of 1960s’ and 1970s’ children’s books were pretty dire – it was, after all, the beginning of the incredible proliferation of young audience targeted “themed” and “problem novels” still plaguing us today, churned out with hyper-focus on the chosen topic to the neglect of strong character development and vivid storytelling.

My rating: 3.5/10.

My late mother, book-a-day reader extraordinaire, who always was happy to delve into a quality “children’s book”, would have categorized this one as a “dull thud”, and that’s where I sadly have to put it too. This writer could do better. If you don’t remember it as a favourite childhood read, perhaps best appreciated by the Streatfeild completest.