Three unrelated novels which share the common theme of adolescent girls coping as best they can with circumstances beyond their control. Frost in May and The World My Wilderness are undeniably much stronger and deeper novels than In Spite of All Terror, which, though competently written, fits more appropriately into the “juvenile historical fiction” category, but I’ve grouped them together here.

Frost in May by Antonia White ~ 1933.

Frost in May by Antonia White ~ 1933.

This edition: Virago, 1981. Introduction by Elizabeth Bowen, 1948. Softcover. ISBN: 0-919630-36-7. 221 pages.

My rating: 8/10

I have known Antonia White as the gifted translator of a number of Colette’s novels, but I hadn’t realized she was an author in her own right until Frost in May crossed my path in an always-worth-examining green-covered Virago edition.

The novel is autobiographical fiction, based on the author’s childhood experiences attending convent school, and was the first in an eventual series of four books following the same character from her ninth through twenty-third year. Following Frost in May are The Lost Traveller, The Sugar House, and Beyond the Glass, and together they give an account of Antonia White’s formative years, and the emotional turmoil which shaped her adult life. The “transgression” in Frost in May which resulted in the fictional Nanda being expelled from convent school is a genuine event, and the real Antonia was marked for life by it.

It is 1908, and nine-year-old Fernanda – Nanda – Grey is being sent to The Convent of the Five Wounds in London in order to immerse her fully in her new life as a dedicated Catholic child; her father’s conversion several years earlier and his fervent seeking after ways to prove his devotion to his new faith have overflowed into Nanda’s life. She worships her father and seeks to please him in every detail of her life, and though she is understandably wary of this new experience, she is prepared to embrace her life among the nuns with eager dedication, as much for his sake as for her own.

Her experience at first is beyond strange to her; being in some ways better than she had anticipated, but also frequently much more harsh. The strict hierarchy of boarding school life is exacerbated by the dictatorial conduct of the nuns. A few are gentle and benign, though even in the kindest the stern core of duty prevents too much softness from showing, several are judgemental, demanding, and deeply sarcastic, seeming to set their young charges up for continual failure, all in aid of “breaking their worldly spirit” in order to prepare them to fully bow down to God.

Nanda tries her best to fit into this new culture, and gets along quite well, though she is continually haunted by feelings of deep inadequacy, both because of her lowly status as a mere convert to the faith rather than a “born” Roman Catholic, and because of her lack of social status among the many wealthy and aristocratic students.

As the years go by, Nanda makes several close friends, though the nuns forbid “particular friendships”, and is well on her way to forming her own ideas as to her adopted religion and her personal relationship with it, when a tragic misunderstanding loses her both her place in the convent community and the love and respect of her adored father.

The novel is a cutting exposé of the hypocrisies of several of the main characters, including Nanda’s demanding father, and her vaguely inefficient mother, and the effect of those hypocrisies on the sensitive and deeply feeling Nanda. She faithfully seeks to please her superiors and to adapt to their wishes and demands, while continually mulling over her own place in the world, and the contradictions she observes.

Very well written, and provides a fascinating account of life in a particular type of convent school. Suitable for competent youthful readers, perhaps early teens and older, but definitely would be most appreciated by those old enough to look back on their own formative years and relate Nanda’s experiences to their own.

The World My Wilderness by Rose Macaulay ~ 1950.

The World My Wilderness by Rose Macaulay ~ 1950.

This edition: Collins, 1950. Hardcover. 253 pages.

My rating: 9.5/10

This fabulous novel deserves more than the rudimentary review I am giving it here; I do believe it is one of the most beautifully written of all I’ve read so far this year. Rose Macaulay lets herself go with lushly vivid descriptions of the world just after the war. The bombed-our ruins of London are depicted in detailed clarity, and almost take precedence over the activities of the human characters, who move through their devastated physical habitat in a state of dazed shock from the brutalities they have seen and survived.

This is a bleakly realistic depiction of the aftermath of World War II and its effect on an expatriate teenager and her divided family, split between France and England. It moved me deeply, though the characters frequently acted in obviously fictional ways. What the author has to say about the effects of war on those who survived it is believably real.

17-year-old Barbary Denison is an English girl who has been raised for many years in France under the custody of her divorced mother and French stepfather. Under the confusion of the German Occupation, Barbary has run wild and has not-so-secretly joined up with an adolescent branch of the resistance – she and her younger half-brother have lived the lives of semi-feral children, and have witnessed and taken part in activities much too old for their tender years. After the war ends, Barbary’s stepfather is mysteriously drowned in the ocean near the family villa; possibly in retaliation for his unenthusiastic but undeniable cooperation with the Germans. Barbary’s mother, a hedonistic artist much more in love with her second husband than anyone fully realizes, emotionally draws away from her children, though Barbary in particular worships her mother with fervent dedication. When it is suggested that Barbary return to England to live with her father, her mother acquiesces with what seems like relief.

The culture shock which Barbary faces in post-war London society is sudden and severe. Her upper-class father has remarried and has a young son; Barbary views her stepmother with scorn and refuses to take any sort of interest in her younger half-brother. Her aunt and cousins are at first amused at her brusqueness and mildly sympathetic – they too have suffered in the war – but Barbary’s sullen refusal to adapt soon turns sympathy into bare tolerance. Barbary falls in with a group of young men who are living a precarious life amongst the bombed-out houses; they survive by petty thefts and view the London police as bitter enemies to be evaded at every turn. Barbary finds in this ragged outlaw world an echo of her wartime life in France, and she enters into a tenuous relationship with these new companions, hiding her activities from her father under guise of studying at the Slade School of Art. He in turn is unwilling to dig too deeply into his daughter’s private life, feeling that giving her space and time will ultimately win her affection.

Tragedy strikes, and Barbary is found out; the consequences of her double life and the bringing together of her estranged parents lead to unexpected revelations, though the reader has had inklings all along of secrets too terrible to be told.

I’ve described this novel as “bleak”, but don’t let that put you off. It’s definitely a worthwhile read, and Rose Macaulay’s satirical wit is in fine working order here. If you liked Crewe Train, or The Towers of Trebizond (which I’ve just finished – very good indeed!) you will be thrilled with The World My Wilderness.

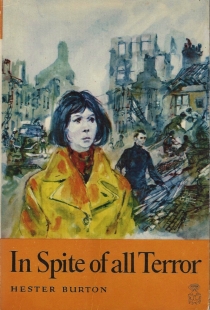

In Spite of All Terror by Hester Burton ~ 1968.

In Spite of All Terror by Hester Burton ~ 1968.

This edition: Oxford University Press, 1970. Softcover. ISBN: 19-272011-2. 150 pages.

My rating: 7.5/10

This next novel is a slight thing compared to the two that preceded it in this post, but it has its merits as well, as a piece of memorable historical fiction. The author has based the story on her own recollections of 1940, when she was a was a 27-year-old Oxford-educated school teacher watching the evacuation of thousands of schoolchildren to the English countryside in preparation for the anticipated bombing of London.

Child of the slums, orphaned fifteen-year-old Liz Hawtin is a scholarship student at a girls’ grammar school; her evacuation in 1939 to the village of Chiddingford is a welcome development, as it spells her escape from the cold and critical aunt who has reluctantly taken on her sister-in-law’s child.

Taken into an aristocratic family, Liz realizes that her own intellectual ability, which is seen as so superior and is so deeply resented by Aunt Ag back in Nile Street, is no more than mediocre compared to the standard set by the intellectual and accomplished Bruton family. Recovering from that humbling hit to her self-esteem, Liz slowly becomes an accepted and valued member of the family, and gains self-confidence and renewed ambition as she is introduced to the greater world beyond her narrow London bounds.

The climactic event of the novel is the evacuation of the Dunkirk soldiers, which Liz experiences from the English side of the Channel. The episodes concerning Dunkirk from the viewpoint of one of the Bruton sons, and descriptions of the Blitz in London are what makes this slightly clichéd book stand out; the scenes are well-described and memorable.

Reading this book, I realize yet again what a wonderful thing well-written juvenile historical fiction can be. For though we all know the basic facts of events such as Dunkirk, it is the creative retellings we read in the impressionable days of our youth which bring so many of these events to life, opening up our minds to future exploration of history both through “adult” fiction and through first person accounts which perhaps are a bit too frank and detailed for a youthful audience.

I also appreciated the author’s refusal to neatly tidy up Liz’s story at the end of the book; we see her poised at the start of the next year in her life, on New Year’s Eve on the brink of 1941, knowing full well that what comes next may be far more challenging than the year she has just come through.

Hester Burton wrote eighteen novels, mostly historical fiction for youth, and she was noted for her meticulous research and her undeniable story-telling abilities. In Spite of All Terror was her sixth book. A vintage author to keep an eye out for if you have history-savvy teens, and for yourself as well. This was a fast read at only 150 pages, but despite its not-too-bothersome flaws (it was a bit too neat and tidy on occasion) it kept me interested all the way through, with abundant period detail adding value to the tale.