The Semi-Detached House by Emily Eden ~ 1859.

The Semi-Detached House by Emily Eden ~ 1859.

This edition: Houghton Mifflin, 1948. Illustrated by Susanne Suba. Hardcover. 216 pages.

My rating: 6.5/10

An aristocratic young Lady Chester, Blanche to her intimates, just eighteen and married six months, is bemoaning her husband’s three-month diplomatic assignment in Germany. She has discovered that she is in an “interesting” state of health, and she thinks her husband’s timing could be ever so much better. As well, Lord Chester has taken the advice of Blanche’s doctor and has packed her off to the depths of the suburbs (Dulham), to Pleasance Court, which is in itself quite all right, being a properly fashionable address, but for the smaller semi-detached dwelling at the rear, residence of the decidedly middle-class Hopkinson family. Blanche is a mass of nerves, anticipating all the worst, and dreading meeting her undoubtedly “common” neighbours.

Just across the shared wall, the Hopkinsons are equally as flustered. Rumour has it that the young socialite moving in next door is either the estranged wife of a member of the nobility, or perhaps (shocked hisses) his chère amie. The very respectable Mrs. Hopkinson has barred her shutters, and intends to cut her new neighbour dead.

Luckily both households make a happy acquaintance and quickly become the best of friends, for this is a very friendly novel of manners, and though the gossip flows freely the gossipers are most well-intentioned.

Emily Eden (“The Honorable Emily Eden” as my 1948 edition proudly proclaims) was a great admirer of her predecessor Jane Austen, and deliberately styled her several domestic novels after that literary mentor. Parallels certainly exist, but Emily Eden’s work has a distinctive voice of its own, being gently satirical and full of humorous situations of a time several decades past that of Jane Austen’s fictional world.

A cheerfully fluffy romp, with just the lightest touches of seriousness here and there, and more than a little snobbishness towards the social climbers seeking to scrape acquaintance with the fashionable Chesters. There are love affairs to be sorted out, and the spanking new marriage to be fully settled into, not to mention the excitement of the impending arrival of Blanche’s addition to the English aristocracy.

Nice glimpse at a world familiar to those of us fond of Miss Austen and her compatriots, written by someone who was familiar at first hand with the life described so vivaciously here.

Another novel, The Semi-Attached Couple, preceded this one, and both are succinctly reviewed by Desperate Reader, and by Redeeming Qualities, among others.

The full text of The Semi-Detached House is online for your reading pleasure here, and both novels are available in a Virago double edition as well, though that may now be out of print.

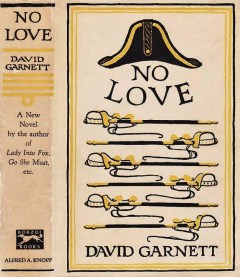

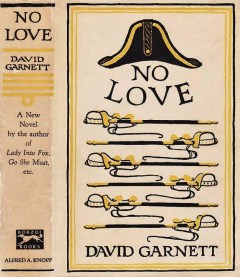

No Love by David Garnett ~ 1929.

No Love by David Garnett ~ 1929.

This edition: Chatto & Windus, 1929. Hardcover. 275 pages.

My rating: 8/10.

What an unexpected and sophisticated novel this one was. I have never read David Garnett before, though of course I have heard quite a lot about Lady Into Fox (which I’m intending to read next year for the Century of Books project) and I now anticipate that reading with even more pleasure, as I was quite pleased with what I read here. I did an online search to see if I could come up with any other reviews of No Love, but have so far drawn a complete blank, which leaves me rather disappointed. Surely someone else has found this novel worthy of discussion? If you have reviewed it yourself, or know of any others who have, I would be greatly interested to read your thoughts.

When in 1885 Roger Lydiate, the second son of the Bishop of Warrington, and himself a young curate, became engaged to Miss Cross, the marriage was looked on with almost universal disapprobation.

Alice Cross was a very emancipated girl; she was the daughter of the great paleontologist, Norman Cross, the notorious freethinker and friend of Huxley’s, who had poisoned himself deliberately when he was dying of cancer. The poor girl idolised her father’s memory, had been known to justify his suicide in public, and openly maintained, not only the non-existence of God, the non-existence of the human soul, and a rational and mechanistic theory of human consciousness, but also carried the war into the enemy’s country by declaring with her favourite poet Lucretius

Tantum religio potuit suadere malorum.

It was her view, constantly expressed, that it was religion alone that had always prevented the advancement and enlightenment of mankind, that all wars and pestilences could be traced to religious causes, and that but for a mistaken belief in God, mankind would already be living in a condition of almost unimaginable material bliss and moral elevation.

She was, they all said, no wife for a clergyman.

Despite Alice’s “unsuitability”, she and Roger were deeply in love, and they did indeed marry, with Roger ultimately abandoning his curateship and declaring himself an atheist. The Bishop let it be known that he was cutting young Roger out of his will, but what was never known was that he was deeply sympathetic to the young couple, and had quietly given the young bride an astounding ten thousand pounds as a wedding gift.

With this unlooked-for nest egg, the young couple purchased a small island near Chichester, on which was an extensive fruit farm, and settled down to a rural life, and to establishing a home and a new way of life.

There is no happiness and excitement in the lives of a married couple greater than the period when they are choosing themselves a house and moving into it; it is a time far happier than the wedding night or than when children come. A house brings no agony with it; its beauties can be seen at once, whilst both physical love and the children it begets, need time for their beauty to unfold.

Roger and Alice were well suited to each other and their rural occupation, and in time two children were born to them, Mabel and Benedict. Life on the Island proceeded peacefully, until one day in late October, 1897, when Roger rescued a stranded party of boaters and offered them hospitality for the night. These proved to be a certain prominent naval man, Admiral Keltie, his beautiful wife, and their young son Simon, and as the two families felt a certain stirring of mutual attraction, it soon came about that the Kelties purchased a building lot on the island and proceeded to construct a mansion, while between the two families a friendship of sorts developed.

That friendship was soon mixed with a good dose of unspoken jealousy, as the Lydiates see at first hand the extravagance of the wealthy Kelties, and as both husbands cast admiring eyes on the attractions of their neighbour’s spouses. Roger is appreciative of Mrs. Keltie’s cold beauty and brittle wit, while the Admiral is moved by Alice’s obvious intelligence, her deeply passionate nature, and a certain earth-mother quality she exudes.

Simon and Benedict make friends as well, though as they grow up they grow apart, with Simon moving in much more exalted circles, and Benedict going his own quiet way, though the two reconnect time and time again, their meetings often marking the episodes of this narrative.

The novel focusses most strongly on the Lydiate family, and its description of their lives and the changes in their moods and attitudes as the Kelties come and go is beautifully wrought. The years pass, and the Great War sweeps both sons away, but the families remain tenuously connected, however, as Simon and Benedict both have fallen in love with the same woman, and her decision on which one to marry has far-reaching consequences to both families.

This novel appeals on numerous levels, as an exercise in story-telling, as a commentary on the social mores of the time, and as a broader examination of the nature of many different kinds of love. Nicely done, David Garnett. I am looking forward to seeking out and reading more by this author in the years to come.

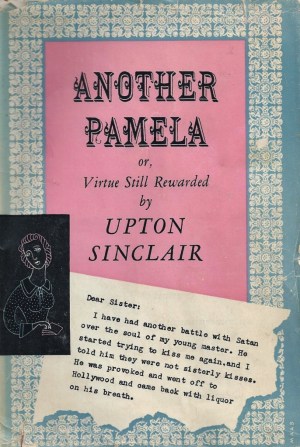

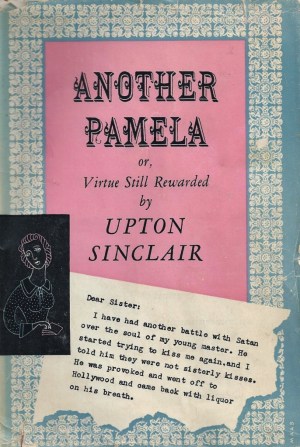

Another Pamela or, Virtue Still Rewarded by Upton Sinclair ~ 1950.

Another Pamela or, Virtue Still Rewarded by Upton Sinclair ~ 1950.

This edition: Viking Press, 1950. Hardcover. 314 pages.

My rating: 7.5/10

And now for something completely different, we move forward in time and to another continent, to this satirical look at social mores in 20th Century California.

Somehow in my travels I have acquired not one but two copies of this slightly obscure novel, a foray into light literature by the famously passionate social activist and best-selling author, Upton Sinclair, perhaps best known for his consciousness-raising, dramatic novel The Jungle.

Having never read Samuel Richardson’s bestselling 1740 epistolary novel, Pamela, about an English serving girl’s trials, tribulations and eventual marriage to the nobleman who tenaciously attempts her seduction, I wasn’t quite sure if I would fully appreciate Upton Sinclair’s parody of the same. It turned out not to matter, as Sinclair helpfully includes generous quotations from the original, having his own heroine read the original as part of her personal development, as she struggles with her own would-be seducer, and the dictates of her conscience and religious upbringing.

Published in 1950, the action of the story is set some years earlier, in the years of the Roaring Twenties, when the fabulously rich of America gave full rein to their imaginative excesses.

The modern Pamela is a child of the early 1900s, being a deeply naïve and (of course!) absolutely lovely young maiden raised in rural poverty in California. She is discovered by a wealthy patroness whose car has broken down in the area of young Pamela’s farm. Upon conversing with Pamela and learning that she is a Seventh Day Adventist with no objection to working on a Sunday (as long as she has Saturday free to devote to her devotions), Mrs. Harris impulsively decides to try the girl out as a parlour maid in her luxurious home, Casa Grande, near Los Angeles.

Pamela is quite naturally overwhelmed by this change in her affairs. Grateful to be able to be sending her pay home to help out her desperately poor family, she is most loquacious in her letters, describing her situation and the other servants and tradespeople she works with, and, increasingly, as she rises in the household hierarchy, the doings of Mrs. Harris herself, who is a lady of many enthusiasms, the main one being the promotion of a rather eclectic form of communism, tweaked to allow for the great disparity between the Harris millions and the theoretical rights of the downtrodden to full equality. (As long as Mrs Harris is not asked to give up her personal comforts, that is.)

And there of course is a “young nobleman” of sorts, one Charles, Mrs Harris’s nephew, a playboy of epic proportions who is completely dependent on his besotted aunt for funds. The Young Master, as Pamela describes him in her letters home, has many vices, not the least of which is his excessive consumption of alcohol, and when Mrs. Harris notices his glances at the lovely Pamela, she encourages the girl to give in to Charles’ pressing invitations to dining out and sightseeing, hoping that this new interest will wean Charles from the demon bottle. (She conveniently turns a blind eye to the possible corruption of her protégé’s morals.)

Charles is decidedly forthcoming; Pamela resists, using her prim and rigid religion as her shield and weapon. Do I need to tell you what happens? Not really, as the title gives the ending away, and as this is a happily satirical tale, we know that Pamela’s eventual fall will be well cushioned.

An enjoyable diversion of a book, with Sinclair getting his digs in at a huge array of social types, all in good fun, with abundant sugar coating the truthful pill within. I wonder if this deserves a “hidden gem” designation? I rather think it does, and I think some of you might find it worthy of a read if you come across it in your travels; it’s an amusingly Americana-ish thing.

Read Full Post »

After the Falls: Coming of Age in the Sixties by Catherine Gildiner ~ 2009. This edition: Vintage, 2010. Softcover. ISBN: 978-0-307-39823-9. 344 pages.

After the Falls: Coming of Age in the Sixties by Catherine Gildiner ~ 2009. This edition: Vintage, 2010. Softcover. ISBN: 978-0-307-39823-9. 344 pages.

Review: War Stories by Gregory Clark

Posted in 1960s, Canadian Book Challenge #7, Read in 2013, tagged Canadian, Canadian Book Challenge 7, Gregory Clark, Memoir, Social Commentary, Vintage, War, War Correspondence, War Stories, World War I, World War II on November 9, 2013| 2 Comments »

My rating: 8/10

Born in 1892 in Toronto, Ontario, Gregory Clark was of perfect age to fight in the Great War, heading to Europe in 1916, at the age of twenty-four. Clark entered the fray as a lieutenant, and exited a major. In the trenches and out of them – Clark received the Military Cross for “conspicuous gallantry” at Vimy Ridge – the young man remembered what he had witnessed, the horror and the gallantry and the moments of respite and delight, to be shared later with his audience of newspaper readers as he took up journalism in the post-war years.

Too old to take active part in World War II, Gregory Clark none the less went overseas once again and pushed his way into the thick of the action, fulfilling a role as a front-line war correspondent, and receiving an Order of the British Empire for his services. Again, his experiences found their way into his short, chatty periodical articles published in the following decades. Clark’s son Murray was killed in action in 1944 while serving with the Regina Rifles, but there is no mention of that personal loss here in War Stories; Clark keeps that particular emotion well buried.

War Stories contains a selection of thirty-eight anecdotes, three to five pages in length, about a wide array of Gregory Clark’s personal experiences. Though the tone throughout is upbeat and frequently humorous – War Stories won the Leacock award for humour in 1965, which rather surprises me, for funny as these anecdotes sometimes are, there is a sombre tone always present – Clark makes it very clear what his opinions are as to the brutality of what the soldiers and civilians went through.

These stories laud the bravery (and the frequent giddy foolishness) of the farm boys and office clerks and travelling salesmen who find themselves caught up in circumstances beyond their most vivid nightmares, fated to kill and, frequently, be horribly maimed, and wastefully killed, merely because of the circumstance of the time of their birth. Something I noticed is that there is not much sympathy shown here for the soldiers of the “other side”; Clark’s thoughts are ever for his own, and he was reportedly a fiercely protective officer of the men under his charge.

All is not muck and death and destruction though. Interludes of inactivity brought forth pranks and hi-jinks, while there were times of repose behind the lines, time for memorable meals and quiet conversation, and musings on what was going to come after, if there was going to be an after.

An appropriate book for this Remembrance Day weekend, this time of sober reflection. Clark reports the realities, but he persists as well in highlighting the lighter moments, the bits of sanity in a world of war.

A good read.

And a much more eloquent review of this book, well worth a click-over, may be found at Canus Humorous.

Read Full Post »