Kilmeny of the Orchard by L.M. Montgomery ~ 1910. This edition: Ryerson Press, 1968. 5th Canadian Printing. Hardcover. 256 pages.

Kilmeny of the Orchard by L.M. Montgomery ~ 1910. This edition: Ryerson Press, 1968. 5th Canadian Printing. Hardcover. 256 pages.

My rating: 3/10. (And I’m being generous.)

*****

Boo, hiss.

I’m going to say this straight away. I did not like this book. If it were authored by anyone other than the iconic Lucy Maud Montgomery, it would already be in the box out in the porch, heading for the charity shop next trip to town. As it is, I will keep it just because I do like complete collections of things, and I have many (most?) of L.M. Montgomery’s other novels and short story collections, but I will not be re-reading it any time soon, if ever.

Oh, this book is so dismal, in so many ways.

Here I extend an apology to those of you who love this story, and see it as a sweet fairytale, and are able to accept it as a product of the time it was written in. That’s all well and good, and I often do the same, but in this case I look at the author in question, see that this novel was published two years after Anne of Green Gables – which is a very different (and much better) book in every conceivable way – and shake my head at the author. How could she?!

In the interests of full disclosure, I did read a number of reviews before I tackled this story, and I was prompted to read this for the Canadian Book Challenge by these two bloggers, Nan at Letters From a Hill Farm, and Christine at The Book Trunk.

Letters From a Hill Farm Review – Kilmeny of the Orchard

The Book Trunk Review – Kilmeny of the Orchard

Nan and Christine between them eloquently present the “for” and “against” arguments, and I was truly curious to see in which camp I would make my home.

Nan, Kilmeny’s all yours.

Hi there, Christine. Is there room for me by your fire?!

Spoilers follow. If you want to read and judge for yourself without my input stop here.

*****

“Kilmeny looked up with a lovely grace,

But nae smile was seen on Kilmeny’s face;

As still was her look, and as still was her ee,

As the stillness that lay on the emerant lea,

Or the mist that sleeps on a waveless sea.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

Such beauty bard may never declare,

For there was no pride nor passion there;

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

Her seymar was the lily flower,

And her cheek the moss-rose in the shower;

And her voice like the distant melodye

That floats along the twilight sea.”

— _The Queen’s Wake_

JAMES HOGG

Wonderfully promising start with a quote from James Hogg’s narrative poem about the lovely Kilmeny who spends seven years in fairy land and comes back mutely unable to tell what she has seen. So far, so good.

And the first few chapters are quite promising as well. We meet a young man, Eric Marshall, as he graduates from college one glorious springtime day, and we nod and smile at Montgomery’s flowery description of the scene.

The sunshine of a day in early spring, honey pale and honey sweet, was showering over the red brick buildings of Queenslea College and the grounds about them, throwing through the bare, budding maples and elms, delicate, evasive etchings of gold and brown on the paths, and coaxing into life the daffodils that were peering greenly and perkily up under the windows of the co-eds’ dressing-room.

A young April wind, as fresh and sweet as if it had been blowing over the fields of memory instead of through dingy streets, was purring in the tree-tops and whipping the loose tendrils of the ivy network which covered the front of the main building. It was a wind that sang of many things, but what it sang to each

listener was only what was in that listener’s heart. To the college students who had just been capped and diplomad by “Old Charlie,” the grave president of Queenslea, in the presence of an admiring throng of parents and sisters, sweethearts and friends, it sang, perchance, of glad hope and shining success and high achievement. It sang of the dreams of youth that may never be quite fulfilled, but are well worth the dreaming for all that. God help the man who has never known such dreams–who, as he leaves his alma mater, is not already rich in aerial castles, the proprietor of many a spacious estate in Spain. He has missed his birthright.

And here’s our young hero:

Eric Marshall, tall, broad-shouldered, sinewy, walking with a free, easy stride, which was somehow suggestive of reserve strength and power, was one of

those men regarding whom less-favoured mortals are tempted seriously to wonder why all the gifts of fortune should be showered on one individual. He was not only clever and good to look upon, but he possessed that indefinable charm of personality which is quite independent of physical beauty or mental ability.

He had steady, grayish-blue eyes, dark chestnut hair with a glint of gold in its waves when the sunlight struck it, and a chin that gave the world assurance of a chin. He was a rich man’s son, with a clean young manhood behind him and splendid prospects before him. He was considered a practical sort of fellow, utterly guiltless of romantic dreams and visions of any sort.

Eric has decided to join his father in the family retail business – his father is a successful department store mogul – much to the dismay of Eric’s older cousin, Dr. David Baker, who feels Eric’s talents would be better used if he were to pursue a law degree. But Eric nobly holds out that his father’s occupation is good enough for him. What a good son, I thought. Attaboy!

But before Eric can settle into his life in business, he receives a letter from a close friend who is working as a teacher on Prince Edward Island. The friend has fallen ill, and must take a leave of absence from his position. Will Eric please come and take over the school for the last part of the term?

Eric happily agrees, and off he goes to the Island. He is much taken by the beauty of the setting, and by the quaint friendliness of the natives. The only jarring note is struck one evening when he sees an elderly man and a young man together.

Eric surveyed them with some curiosity. They did not look in the least like the ordinary run of Lindsay people. The boy, in particular, had a distinctly foreign appearance, in spite of the gingham shirt and homespun trousers, which seemed to be the regulation, work-a-day outfit for the Lindsay farmer lads. He

had a lithe, supple body, with sloping shoulders, and a lean, satiny brown throat above his open shirt collar. His head was covered with thick, silky, black curls, and the hand that hung down by the side of the wagon was unusually long and slender. His face was richly, though somewhat heavily featured, olive

tinted, save for the cheeks, which had a dusky crimson bloom. His mouth was as red and beguiling as a girl’s, and his eyes were large, bold and black. All in all, he was a strikingly handsome fellow; but the expression of his face was sullen, and he somehow gave Eric the impression of a sinuous, feline creature basking in lazy grace, but ever ready for an unexpected spring.

The other occupant of the wagon was a man between sixty-five and seventy, with iron-gray hair, a long, full, gray beard, a harsh-featured face, and deep-set hazel eyes under bushy, bristling brows. He was evidently tall, with a spare, ungainly figure, and stooping shoulders. His mouth was close-lipped and

relentless, and did not look as if it had ever smiled. Indeed, the idea of smiling could not be connected with this man–it was utterly incongruous. Yet there was nothing repellent about his face; and there was something in it that compelled Eric’s attention.

Eric shrugs and moves on. That evening, his landlord fills him in on the story. The elderly man Thomas Gordon, a local farmer, and the boy is an Italian orphan whose mother died at his birth. His father immediately deserted and has not been seen since. He was raised up by the Gordons, bachelor Thomas and his spinster sister Janet, but nature is apparently proving stronger than nurture.

“Anyhow, they kept the baby. They called him Neil and had him baptized same as any Christian child. He’s always lived there. They did well enough by him. He was sent to school and taken to church and treated like one of themselves. Some folks think they made too much of him. It doesn’t always do with that kind, for ‘what’s bred in bone is mighty apt to come out in flesh,’ if ‘taint kept down pretty well. Neil’s smart and a great worker, they tell me. But folks hereabouts don’t like him. They say he ain’t to be trusted further’n you can see him, if as far…

Later this same evening, Eric goes for a walk and stumbles upon an old orchard, trees in full bloom. Wandering through the fragrant dusk, he hears the delicate strains of a violin, and, tracing them to their source, startles a lovely young maiden playing ethereal and perfectly in-tune music among the apple trees. Eric thinks she’s the most beautiful thing he’s ever seen, and eagerly approaches her but the girl gasps in terror and flees, uttering not a word or a sound.

More investigation reveals that this is the mysterious Kilmeny Gordon, niece of the afore-mentioned Thomas and Janet Gordon, and house mate of Italianate Neil. She lives in seclusion and seldom appears in public; apparently she is mute, and also is cursed by being an illegitimate child. Her mother was married to a man, Ronald Fraser, whose first wife was mistakenly thought to be dead; when the first wife showed up very much alive. Ronald abandoned wife number two and went off with wife number one, to die “of a broken heart” shortly thereafter. Kilmeny is born into an atmosphere of grief and resentment, and has been unable to speak since birth, though apparently her “organs of speech” are normal enough. Kilmeny’s mother is quite a piece of work – sullen and angry at her sad fate, she takes it out on everyone in the family, and I can’t help but think her death, which has occurred three years prior to the opening of the story, was probably a huge relief to all concerned.

I’m going to condense the rest of the story, though you can probably figure out what happens next.

Neil is already in love with Kilmeny. Eric falls in love with her and dismisses the prior claim of the shifty Italian fellow. Kilmeny communicates through the strains of her violin music (Neil, also innately musically gifted by his inborn heritage, apparently only had to show her how to hold the bow and her vast natural ability did the rest) and by writing on a slate hung around her neck. The courtship proceeds with Eric marvelling at this luscious find – a pure, innocent, beautiful girl – all his! Oh, go slow, do not frighten the shy little thing! – and with Kilmeny totally in awe of this handsome, obviously noble, manly man from another world.

And oh yes, the locals all call Eric “Master”, presumably because of his schoolmaster role, but it sounds a little odd in daily conversation, as if it should be accompanied (and it often is) by forelock tugging of the peasant-before-nobility type.

Eric is predictably infatuated with Kilmeny, and persists in haunting the orchard in her company, until his landlady mentions that perhaps it would be nice if Eric would go to Kilmeny’s guardians and mention his interest. “Never thought of that!” says Eric (I’m paraphrasing) and off he goes to immediately win over the dour and suspicious Gordons with his shining goodness and innate nobility. (Neil glowers in the corner.)

What else? Let’s see. Oh – Kilmeny wonders at why Eric is so taken with her – “I’m so ugly!” she moans – oops, sorry – writes on her slate. Turns out that she has never looked in a mirror in her whole eighteen years – her mother broke them all in a fit of pique after her abandonment, and Janet and Thomas have never thought to replace them.

Eric proposes, because despite Kilmeny’s “great affliction” he can’t wait to get his hands on this delectable young creature. Kilmeny refuses him. Scritch, scritch, scritch -“I will only marry you if I gain the power of speech!”

Eric calls in his old friend Dr. Baker, who examines Kilmeny and decides, along with her aunt and uncle, that her affliction has been caused by her mother’s trauma, visited in some mysterious way upon the newborn babe. If a great surge of desire to speak were to come over Kilmeny, she would at long last be able to utter! But as this doesn’t seem likely to happen, Kilmeny and Eric decide to part.

Both mope around, until Eric, unable to withstand the desire to see his love one more time, ventures into the orchard. He passes sullen Neil, building a fence. He sees Kilmeny, and is overcome with grief and sorrow at his imminent loss. Kilmeny sees him, and she sees something else – the hot-blooded Italian is coming up behind Eric with axe upraised!

Do I need to go on?

Voice is achieved. Neil drops the axe in horrified remorse and promptly leaves the Island, removing himself permanently from the picture, to the relief of absolutely everyone. (Poor Neil. He is the one sympathetic character in this whole thing.) The engagement is back on. Eric’s father sees Kilmeny and is immediately smitten with his son’s bucolic sweetheart. Birds sing, etc. etc. etc. and the curtain sweeps shut.

*****

There are so many objectionable elements to this melodrama. The characters are impossibly stereotyped, and the situations are contrived to the nth degree.

What was all the nonsense about Neil and his ethnic “stain”? He was raised from babyhood as a member of the family, but his demotion from Kilmeny’s foster “brother” to merely an inconvenient hired boy is swift and brutal, with no visible consequences except to Neil himself. The xenophobic comments regarding Neil’s heritage come straight from the author, via the mouths of her characters. Nowhere is there any indication that this is a plot device, except for one or two mentions that Neil’s perpetual sullenness is a reaction to the way he is viewed and treated by everyone else in his community. Damned from birth, and by birth.

And poor Kilmeny – she too is damned by birth. Because of her mother’s “sin” – rejection of her dying father’s request for a reconciliation, plus a poor marital choice – the innocent baby is doomed by some supernatural power to muteness. That doesn’t make any sort of sense whatsoever, but all of the characters meekly accept it as a viable reason and a fair enough fate.

Eric’s infatuation with the virginal Kilmeny, and his desire to teach her about love and the world is more than a little creepy, as is his willingness to abandon her because of her “affliction”. I mean, the girl has everything – unearthly beauty, musical ability approaching genius, and perfect (if tiny) handwriting! What’s a mere voice matter when she has so many other sterling qualities and delicious possibilities to offer?

The whole thing creeped me out, and I’m hard pressed to find any excuse for Lucy Maud Montgomery’s authorial sloppiness and moral negligence in this particular effort. It did remind me of some of the more forgettable of her short stories, so all I can think is that she popped it off one thoughtless day and sent it out into the world and had it accepted because of the previous excellence and best-sellerism of Anne of Green Gables and Anne of Avonlea.

Not recommended.

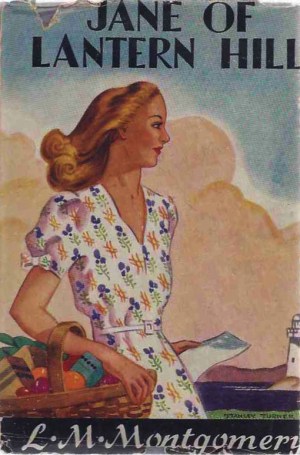

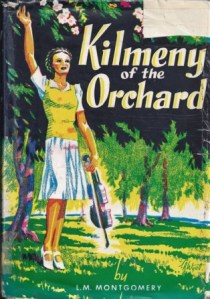

Oh – one more thing. What is with that awful cover, pictured way above? Kilmeny looks dressed for 1940s’ tennis, but for the improbable shoes. This novel was set in horse and buggy times, dear illustrator – it was originally published in 1910! And she looks like a sturdy, athletic Nordic blond – in the book she is a delicately featured, blue-eyed, black-haired, “fairy child”. Apparently a cover illustration with only a tenuous relation to the text within is not a modern phenomenon.

Read Full Post »

I Was a Teenage Katima-Victim: A Canadian Odyssey by Will Ferguson ~ 1998. This edition: Douglas & McIntyre, 1998. Softcover. ISBN: 1-55054-652-x. 259 pages.

I Was a Teenage Katima-Victim: A Canadian Odyssey by Will Ferguson ~ 1998. This edition: Douglas & McIntyre, 1998. Softcover. ISBN: 1-55054-652-x. 259 pages.