Getting ready to unfurl – leaf buds at University of British Columbia Botanical Garden, late February, 2014.

Well, here we are at the end of March, with the year one quarter over, and there is a largish stack of books read in January-February-March sitting here and nagging at my conscience. They all deserve some sort of mention, ideally a post each all to themselves, but with spring coming and longer daylight hours and some serious gardening projects coming up (meaning somewhat less computer time for me – which is by and large a good thing – hurray!) I know that I will not get to them all.

So I think a series of round up posts is in order, to temporarily clear my desk and my conscience, and to allow me to shelve these ones and recreate a new stack over the next few months, because that pattern or reading/posting is inevitable, it seems.

I’ve been considering how best to present these (there are quite a few) and have sorted them very loosely into sort-of-related groupings. Here’s the first lot, then.

All four of these particular books are linked by general era – just before, during and just after the Great War, and by their vivid reflection of the times they are set in. From playful (Christopher and Columbus) to sincere (The Green Bay Tree and The Home-Maker) to bizarre (Her Father’s Daughter), all help to fill in background details against which to set other books, and all are engrossing fictions in their own disparate ways.

************

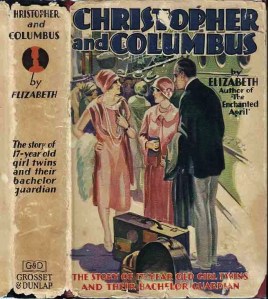

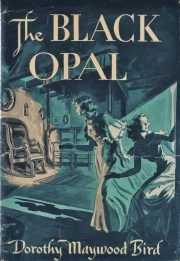

Not my copy – I have a much more recent Virago – but a nice early issue dust jacket depiction too good to not share.

Christopher and Columbus by Elizabeth von Arnim ~ 1919. This edition: Virago, 1994. Paperback. ISBN: 1-85381-748-1. 500 pages.

My rating: 8/10

Charming and playful, with a serious undertone regarding wartime attitudes to “enemy aliens”, set as it is in the early years of the Great War, in England and America.

Their names were really Anna-Rose and Anna-Felicitas; but they decided, as they sat huddled together in a corner of the second-class deck of the American liner St. Luke, and watched the dirty water of the Mersey slipping past and the Liverpool landing-stage disappearing into mist, and felt that it was comfortless and cold, and knew they hadn’t got a father or a mother, and remembered that they were aliens, and realized that in front of them lay a great deal of gray, uneasy, dreadfully wet sea, endless stretches of it, days and days of it, with waves on top of it to make them sick and submarines beneath it to kill them if they could, and knew that they hadn’t the remotest idea, not the very remotest, what was before them when and if they did get across to the other side, and knew that they were refugees, castaways, derelicts, two wretched little Germans who were neither really Germans nor really English because they so unfortunately, so complicatedly were both,—they decided, looking very calm and determined and sitting very close together beneath the rug their English aunt had given them to put round their miserable alien legs, that what they really were, were Christopher and Columbus, because they were setting out to discover a New World.

Total digression – check out the paragraph above. It is ONE sentence. Thank you, E von A, because now I don’t feel quite so bad about my own rambling tendencies!

Ahem. Back to our story. To condense completely, the two Annas, having been rejected by their English connections, are sent off to America (this is before the Americans have joined in the war) to be settled upon some distant acquaintances there. Everything goes awry, but luckily the two girls – they are twins, by the way – have gained a sponsor/mentor/protector in the person of Mr. Twist, a fellow passenger, who just happens to be wealthy young man with a strong maternal streak.

The three adventure across America – the twins getting into continual scrapes and Mr. Twist rescuing them from themselves – eventually ending in California, where they acquire a chaperone and a Chinese cook, and decide to open an English-style teashop. It is a blazing success, but not in the way they had planned…

Very much in the style of The Enchanted April, more than slightly farcical, with romantically tidy endings for all.

Internet reviews abound, and this is happily available at Project Gutenberg: Christopher and Columbus

Her Father’s Daughter by Gene Stratton-Porter ~ 1921. This edition: Doubleday, 1921. Hardcover. 486 pages.

Her Father’s Daughter by Gene Stratton-Porter ~ 1921. This edition: Doubleday, 1921. Hardcover. 486 pages.

My rating: 2/10

Talk about contrast between books of a similar vintage, between this one and the previous Elizabeth von Arnim confection. This next book was a shocker, and I disliked it increasingly intensely, forcing myself to keep reading because I was determined to see where the author was going to go with it. (Nowhere very good, as it turns out.)

I already had an uneasy relationship with Gene Stratton-Porter, and though I’d been forewarned by other reviewers about the deeply racist overtones of Her Father’s Daughter, I wasn’t prepared to have the “race issue” as such a major plot point.

Two teenage sisters are orphaned. The elder sister spends their joint income on herself, on her lavish wardrobe and gadding about, while the younger sister is left to her own dismal devices.

Luckily sister # 2, our heroine, Linda, is a young lady of vast resource and apparently limitless talents. She pseudonymously writes and illustrates popular articles on California wild plants and flowers, excels at her high school courses, and has attained the selfless dedication of the family cook/housekeeper, a brogue-inflicted Irishwoman, one Katy. (GS-P’s dialect mangling reaches new heights in this book.)

Linda also tootles about in her late father’s car, a Stutz Bear Cat, driving everywhere fast, and as it goes without saying, better than all the boys. There’s nothing this girl doesn’t excel at, and her acquaintance ooh and ah over her many accomplishments, and chuck their devotion at her feet. She’s ultimately so all-round darned smart and gorgeous and generally desirable – especially once she bullies her sister into ponying up some of Daddy’s cash so she can buy a few new dresses – that she attracts three suitors, two of them older men, and one a high school classmate.

Which brings us to the race angle. For in the high school class the teenage suitor attends, there is a Japanese boy, who is at the top of the class despite all efforts of Linda’s Boyfriend to displace Japanese Guy. So Linda wracks her brains to find a way to help Boyfriend beat “the Jap”. Says she:

“They are quick; oh! they are quick; and they know from their cradles what it is that they have in the backs of their heads. We are not going to beat them driving them to Mexico or to Canada, or letting them monopolize China. That is merely temporizing. That is giving them fertile soil on which to take the best of their own and the level best of ours, and by amalgamating the two, build higher than we ever have. There is just one way in all this world that we can beat Eastern civilization and all that it intends to do to us eventually. The white man has dominated by his color so far in the history of the world, but it is written in the Books that when the men of color acquire our culture and combine it with their own methods of living and rate of production, they are going to bring forth greater numbers, better equipped for the battle of life, than we are. When they have got our last secret, constructive or scientific, they will take it, and living in a way that we would not, reproducing in numbers we don’t, they will beat us at any game we start, if we don’t take warning while we are in the ascendancy, and keep there.”

And this:

“Take them as a race, as a unit—of course there are exceptions, there always are—but the great body of them are mechanical. They are imitative. They are not developing anything great of their own in their own country. They are spreading all over the world and carrying home sewing machines and threshing machines and automobiles and cantilever bridges and submarines and aeroplanes—anything from eggbeaters to telescopes. They are not creating one single thing. They are not missing imitating everything that the white man can do anywhere else on earth. They are just like the Germans so far as that is concerned.”

And then this:

“Linda,” said the boy breathlessly, “do you realize that you have been saying ‘we’? Can you help me? Will you help me?”

“No,” said Linda, “I didn’t realize that I had said ‘we.’ I didn’t mean two people, just you and me. I meant all the white boys and girls of the high school and the city and the state and the whole world. If we are going to combat the ‘yellow peril’ we must combine against it. We have got to curb our appetites and train our brains and enlarge our hearts till we are something bigger and finer and numerically greater than this yellow peril. We can’t take it and pick it up and push it into the sea. We are not Germans and we are not Turks. I never wanted anything in all this world worse than I want to see you graduate ahead of Oka Sayye. And then I want to see the white boys and girls of Canada and of England and of Norway and Sweden and Australia, and of the whole world doing exactly what I am recommending that you do in your class and what I am doing personally in my own. I have had Japs in my classes ever since I have been in school, but Father always told me to study them, to play the game fairly, but to BEAT them in some way, in some fair way, to beat them at the game they are undertaking.”

Well, Japanese Guy soon realizes that something is up, because suddenly Boyfriend is pulling ahead in Algebra. (Or was it Trigonometry?) All because Linda is now helping Boyfriend study and has given him many words of encouragement. And then Linda and Boyfriend start to suspect that Japenese Guy is not a mere teenager like themselves, but an older man who is dying his hair and using cosmetics to make himself look younger. And then the gloves are off on both sides.

Subplots concerning sister and the inheritance and a friend who is an aspiring architect and more skulduggery concerning both of those scenarios, with the whole thing ending in a murder attempt by Japanese Guy upon Boyfriend, and his (Japanese Guy’s) death at the hand of Linda’s Irish servant Katy. Luckily killing a dirty yellow Jap is all in a day’s work in this neck of the woods:

“Judge Whiting, I had the axe round me neck by the climbin’ strap, and I got it in me fingers when we heard the crature comin’, and against his chist I set it, and I gave him a shove that sint him over. Like a cat he was a-clingin’ and climbin’, and when I saw him comin’ up on us with that awful face of his, I jist swung the axe like I do when I’m rejoocin’ a pace of eucalyptus to fireplace size, and whack! I took the branch supportin’ him, and a dome’ good axe I spoiled din’ it.”

Katy folded her arms, lifted her chin higher than it ever had been before, and glared defiance at the Judge.

“Now go on,” she said, “and decide what ye’ll do to me for it.”

The Judge reached over and took both Katherine O’Donovan’s hands in a firm grip.

“You brave woman!” he said. “If it lay in my power, I would give you the Carnegie Medal. In any event I will see that you have a good bungalow with plenty of shamrock on each side of your front path, and a fair income to keep you comfortable when the rheumatic days are upon you.”

By the end Linda has nabbed control of the family fortune, the sister has received a severe humbling, and the architect friend wins the prize. (And Japanese Guy is dead and vanished, his body mysteriously spirited away by “confederates”, adding a strange conspiracy theory sort of twist to the saga. All I could think was, “All that for academic standing in a high school class? Really? Really, Gene Stratton-Porter???!”)

Linda predictably finds true love, not with Teenage Boyfriend but with Older Man with Lots of Money and A Very Nice House built up amongst the wildflowers in Linda’s favourite roaming ground. How very handy.

Trying to think what I left this unsettling bit of vintage paranoia two points for. I guess because I did keep reading. But it was thoroughly troubling from start to finish on a multitude of levels – the racist thing being only one of the points that jarred – and even the gushing descriptions of California flora didn’t really salvage it.

Not recommended, unless you are a Gene Stratton-Porter completest. Not a very pretty tale, but if you wish to see for yourself, here it is at Project Gutenberg: Her Father’s Daughter

Will I read more books by this writer? Yes, very probably. For the curiousity factor, if nothing else, because these were hugely popular in their time, and that tells an awful lot (pun intended) about the general attitude of the populace who found these appealing, and they do much to enrich our background picture of an era.

The Green Bay Tree by Louis Bromfield ~ 1924. This edition: Pocket Books, 1941. Paperback. 356 pages.

The Green Bay Tree by Louis Bromfield ~ 1924. This edition: Pocket Books, 1941. Paperback. 356 pages.

My rating: 7/10

Moving on just a year or two, to this family saga by American writer Louis Bromfield, who served in the French Army during the First World War, and subsequently lived in France for thirteen years, before resettling in the United States and dedicating himself to the improvement of American agriculture by establishing the famous Malabar Farm in Ohio.

Bromfield was a prolific and exceedingly popular writer of his time, winning the Pulitzer Prize in 1927 for his third novel, Early Autumn. 1924’s The Green Bay Tree was his first published work, and it was immediately successful, paving the way for his stellar future writing career.

This is a book which fits neatly into the family saga genre, focussing on one main character, the wealthy and strong-willed Julia Thane, but surrounding her with a constellation of competently drawn characters all carrying on full lives of their own, which we glimpse and appreciate as they bump up against Julia in her blazing progress from the American family mansion surrounded by steel mills to the secluded house in France, where she settles with her secret illegitimate child and remakes her life very much on her terms.

Bromfield, in addition to creating a strong female lead and allowing her much scope for personal activity, also has a sociopolitical angle which he persistently presents, in the major sideplot of ongoing labour unrest in the steel mills surrounding the Shane family mansion, and widening the focus to the greater situation right across industrial America, with the hard-fought battle for workers’ rights and labour unions, and the rise of Russian Communism and its ripple effect which spreads across the globe.

Late in the story Lily Shane is caught up in the German invasion of France at the start of the Great War, and though this section is reasonably well-depicted, it was a bit too conveniently rounded off, with the author fast-forwarding to the end of the war with very few details after Lily’s one big dramatic scene.

It took me a chapter or two to fully enter into the story, but once my attention was caught I cheerfully went along for the ride. Bromfield is a smooth writer, and though this occasionally whispers “first novel” in slight awkwardness of phrasing and sketchiness of scene, by and large it is a nicely polished example of its type.

Bromfield seems to be something of a forgotten author nowadays, which is a shame, as his novels are certainly as engrossing (if not more so) than many of those now heading the contemporary bestseller lists. More on Bromfield in the future, I promise.

The Home-Maker by Dorothy Canfield ~ 1924. This edition: Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1924. Hardcover. 320 pages.

The Home-Maker by Dorothy Canfield ~ 1924. This edition: Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1924. Hardcover. 320 pages.

My rating: 8.5/10

Saving the best for last, here is a book I had been looking forward to for quite some time, after seeing it featured on the Persephone Press reprint list, and reading such stellar reviews by so many book bloggers.

It was very good indeed, though I found that the ending was vaguely unsatisfactory to me personally, involving as it did an unstated conspiracy between several of the characters to continue with a serious misrepresentation in order to allow a societal blind eye being turned to an unconventional family arrangement. I think I would have preferred an open discussion, rather than a sweeping under the rug sort of conclusion. But that’s just me… This novel must have been rather hard to round off neatly once the author had taken it as far as she thought her audience would swallow, and she decidedly had made her point and was likely ready to move on.

An ineffectually dreamy man labors on at an uncongenial job, while his wife keeps the house polished to the highest standard possible, and receives accolades from all levels of the social hierarchy of the small New England town where the family lives for her obvious achievement of wifely and motherly perfect devotion. Meanwhile the family’s three children are showing very obvious symptoms of psychological distress: excessive shyness (the oldest girl), a perennially wonky digestion (middle boy), and determined naughtiness (youngest boy).

Husband loses his job and on the way home to break the news has a terrible “accident”; he ends up in a wheelchair and the wife forays forth into the working world. And wouldn’t you know it? Suddenly everyone is much happier, and the children’s issues start to resolve “all on their own”. But the husband is healing much more fully than at first it was feared. How will this all end, in 1920s’ small town America, where gender roles are by and large carved in granite?

A lovely book, and extremely readable for its keen examination of the marital relationship it portrays, and its touching details of family life and the woes and joys of childhood.

Where it lost its few points with me was in the unlikely perfection of the wife’s experience in the working world; she waltzed right in and was promoted up the department store ladder of responsibility remarkably easily; even allowing for her detail-freak perfectionism her immediate grasp of her new role in life was a bit hard to swallow, as was her sudden relaxation regarding less than stellar household cleanliness. And I was uncomfortable with the “easy” ending, as I mentioned earlier.

I’ve read a number of other Dorothy Canfield Fisher novels, and they share this same occasional over-simplification as the author hammers her point home – she was something of a crusader in the area of improving family life and giving a fuller and freer role to children – but as she is also a marvelous story teller we can allow her this tiny tendency, I think.

************

Of the four books in this grouping, if I were going to recommend one as a should-read, it would definitely be The Home-Maker.

Followed by Christopher and Columbus, because it is utterly charming, if a bit silly in its premises and occasionally rather wordy. The Green Bay Tree is a perfectly acceptable drama, though nothing extraordinary. As for Her Father’s Daughter, consider yourself forewarned!

Read Full Post »

The Case of the Shoplifter’s Shoe by Erle Stanley Gardner ~ 1938. This edition: Pocket Books, 1945. Paperback. 230 pages.

The Case of the Shoplifter’s Shoe by Erle Stanley Gardner ~ 1938. This edition: Pocket Books, 1945. Paperback. 230 pages.

Round-Up Post #1-2014: Elizabeth von Arnim, Gene Stratton Porter, Louis Bromfield, Dorothy Canfield Fisher

Posted in 1910s, 1920s, Bromfield, Louis, Century of Books - 2014, Fisher, Dorothy Canfield, Read in 2014, Stratton-Porter, Gene, von Arnim, Elizabeth, tagged Bromfield, Louis, Century of Books 2014, Christopher and Columbus, Fisher, Dorothy Canfield, Her Father's Daughter, Social Commentary, Stratton-Porter, Gene, The Green Bay Tree, The Home-Maker, Vintage Fiction, von Arnim, Elizabeth on April 1, 2014| 12 Comments »

Getting ready to unfurl – leaf buds at University of British Columbia Botanical Garden, late February, 2014.

Well, here we are at the end of March, with the year one quarter over, and there is a largish stack of books read in January-February-March sitting here and nagging at my conscience. They all deserve some sort of mention, ideally a post each all to themselves, but with spring coming and longer daylight hours and some serious gardening projects coming up (meaning somewhat less computer time for me – which is by and large a good thing – hurray!) I know that I will not get to them all.

So I think a series of round up posts is in order, to temporarily clear my desk and my conscience, and to allow me to shelve these ones and recreate a new stack over the next few months, because that pattern or reading/posting is inevitable, it seems.

I’ve been considering how best to present these (there are quite a few) and have sorted them very loosely into sort-of-related groupings. Here’s the first lot, then.

All four of these particular books are linked by general era – just before, during and just after the Great War, and by their vivid reflection of the times they are set in. From playful (Christopher and Columbus) to sincere (The Green Bay Tree and The Home-Maker) to bizarre (Her Father’s Daughter), all help to fill in background details against which to set other books, and all are engrossing fictions in their own disparate ways.

************

Not my copy – I have a much more recent Virago – but a nice early issue dust jacket depiction too good to not share.

Christopher and Columbus by Elizabeth von Arnim ~ 1919. This edition: Virago, 1994. Paperback. ISBN: 1-85381-748-1. 500 pages.

My rating: 8/10

Charming and playful, with a serious undertone regarding wartime attitudes to “enemy aliens”, set as it is in the early years of the Great War, in England and America.

Total digression – check out the paragraph above. It is ONE sentence. Thank you, E von A, because now I don’t feel quite so bad about my own rambling tendencies!

Ahem. Back to our story. To condense completely, the two Annas, having been rejected by their English connections, are sent off to America (this is before the Americans have joined in the war) to be settled upon some distant acquaintances there. Everything goes awry, but luckily the two girls – they are twins, by the way – have gained a sponsor/mentor/protector in the person of Mr. Twist, a fellow passenger, who just happens to be wealthy young man with a strong maternal streak.

The three adventure across America – the twins getting into continual scrapes and Mr. Twist rescuing them from themselves – eventually ending in California, where they acquire a chaperone and a Chinese cook, and decide to open an English-style teashop. It is a blazing success, but not in the way they had planned…

Very much in the style of The Enchanted April, more than slightly farcical, with romantically tidy endings for all.

Internet reviews abound, and this is happily available at Project Gutenberg: Christopher and Columbus

My rating: 2/10

Talk about contrast between books of a similar vintage, between this one and the previous Elizabeth von Arnim confection. This next book was a shocker, and I disliked it increasingly intensely, forcing myself to keep reading because I was determined to see where the author was going to go with it. (Nowhere very good, as it turns out.)

I already had an uneasy relationship with Gene Stratton-Porter, and though I’d been forewarned by other reviewers about the deeply racist overtones of Her Father’s Daughter, I wasn’t prepared to have the “race issue” as such a major plot point.

Two teenage sisters are orphaned. The elder sister spends their joint income on herself, on her lavish wardrobe and gadding about, while the younger sister is left to her own dismal devices.

Luckily sister # 2, our heroine, Linda, is a young lady of vast resource and apparently limitless talents. She pseudonymously writes and illustrates popular articles on California wild plants and flowers, excels at her high school courses, and has attained the selfless dedication of the family cook/housekeeper, a brogue-inflicted Irishwoman, one Katy. (GS-P’s dialect mangling reaches new heights in this book.)

Linda also tootles about in her late father’s car, a Stutz Bear Cat, driving everywhere fast, and as it goes without saying, better than all the boys. There’s nothing this girl doesn’t excel at, and her acquaintance ooh and ah over her many accomplishments, and chuck their devotion at her feet. She’s ultimately so all-round darned smart and gorgeous and generally desirable – especially once she bullies her sister into ponying up some of Daddy’s cash so she can buy a few new dresses – that she attracts three suitors, two of them older men, and one a high school classmate.

Which brings us to the race angle. For in the high school class the teenage suitor attends, there is a Japanese boy, who is at the top of the class despite all efforts of Linda’s Boyfriend to displace Japanese Guy. So Linda wracks her brains to find a way to help Boyfriend beat “the Jap”. Says she:

And this:

And then this:

Well, Japanese Guy soon realizes that something is up, because suddenly Boyfriend is pulling ahead in Algebra. (Or was it Trigonometry?) All because Linda is now helping Boyfriend study and has given him many words of encouragement. And then Linda and Boyfriend start to suspect that Japenese Guy is not a mere teenager like themselves, but an older man who is dying his hair and using cosmetics to make himself look younger. And then the gloves are off on both sides.

Subplots concerning sister and the inheritance and a friend who is an aspiring architect and more skulduggery concerning both of those scenarios, with the whole thing ending in a murder attempt by Japanese Guy upon Boyfriend, and his (Japanese Guy’s) death at the hand of Linda’s Irish servant Katy. Luckily killing a dirty yellow Jap is all in a day’s work in this neck of the woods:

By the end Linda has nabbed control of the family fortune, the sister has received a severe humbling, and the architect friend wins the prize. (And Japanese Guy is dead and vanished, his body mysteriously spirited away by “confederates”, adding a strange conspiracy theory sort of twist to the saga. All I could think was, “All that for academic standing in a high school class? Really? Really, Gene Stratton-Porter???!”)

Linda predictably finds true love, not with Teenage Boyfriend but with Older Man with Lots of Money and A Very Nice House built up amongst the wildflowers in Linda’s favourite roaming ground. How very handy.

Trying to think what I left this unsettling bit of vintage paranoia two points for. I guess because I did keep reading. But it was thoroughly troubling from start to finish on a multitude of levels – the racist thing being only one of the points that jarred – and even the gushing descriptions of California flora didn’t really salvage it.

Not recommended, unless you are a Gene Stratton-Porter completest. Not a very pretty tale, but if you wish to see for yourself, here it is at Project Gutenberg: Her Father’s Daughter

Will I read more books by this writer? Yes, very probably. For the curiousity factor, if nothing else, because these were hugely popular in their time, and that tells an awful lot (pun intended) about the general attitude of the populace who found these appealing, and they do much to enrich our background picture of an era.

My rating: 7/10

Moving on just a year or two, to this family saga by American writer Louis Bromfield, who served in the French Army during the First World War, and subsequently lived in France for thirteen years, before resettling in the United States and dedicating himself to the improvement of American agriculture by establishing the famous Malabar Farm in Ohio.

Bromfield was a prolific and exceedingly popular writer of his time, winning the Pulitzer Prize in 1927 for his third novel, Early Autumn. 1924’s The Green Bay Tree was his first published work, and it was immediately successful, paving the way for his stellar future writing career.

This is a book which fits neatly into the family saga genre, focussing on one main character, the wealthy and strong-willed Julia Thane, but surrounding her with a constellation of competently drawn characters all carrying on full lives of their own, which we glimpse and appreciate as they bump up against Julia in her blazing progress from the American family mansion surrounded by steel mills to the secluded house in France, where she settles with her secret illegitimate child and remakes her life very much on her terms.

Bromfield, in addition to creating a strong female lead and allowing her much scope for personal activity, also has a sociopolitical angle which he persistently presents, in the major sideplot of ongoing labour unrest in the steel mills surrounding the Shane family mansion, and widening the focus to the greater situation right across industrial America, with the hard-fought battle for workers’ rights and labour unions, and the rise of Russian Communism and its ripple effect which spreads across the globe.

Late in the story Lily Shane is caught up in the German invasion of France at the start of the Great War, and though this section is reasonably well-depicted, it was a bit too conveniently rounded off, with the author fast-forwarding to the end of the war with very few details after Lily’s one big dramatic scene.

It took me a chapter or two to fully enter into the story, but once my attention was caught I cheerfully went along for the ride. Bromfield is a smooth writer, and though this occasionally whispers “first novel” in slight awkwardness of phrasing and sketchiness of scene, by and large it is a nicely polished example of its type.

Bromfield seems to be something of a forgotten author nowadays, which is a shame, as his novels are certainly as engrossing (if not more so) than many of those now heading the contemporary bestseller lists. More on Bromfield in the future, I promise.

My rating: 8.5/10

Saving the best for last, here is a book I had been looking forward to for quite some time, after seeing it featured on the Persephone Press reprint list, and reading such stellar reviews by so many book bloggers.

It was very good indeed, though I found that the ending was vaguely unsatisfactory to me personally, involving as it did an unstated conspiracy between several of the characters to continue with a serious misrepresentation in order to allow a societal blind eye being turned to an unconventional family arrangement. I think I would have preferred an open discussion, rather than a sweeping under the rug sort of conclusion. But that’s just me… This novel must have been rather hard to round off neatly once the author had taken it as far as she thought her audience would swallow, and she decidedly had made her point and was likely ready to move on.

An ineffectually dreamy man labors on at an uncongenial job, while his wife keeps the house polished to the highest standard possible, and receives accolades from all levels of the social hierarchy of the small New England town where the family lives for her obvious achievement of wifely and motherly perfect devotion. Meanwhile the family’s three children are showing very obvious symptoms of psychological distress: excessive shyness (the oldest girl), a perennially wonky digestion (middle boy), and determined naughtiness (youngest boy).

Husband loses his job and on the way home to break the news has a terrible “accident”; he ends up in a wheelchair and the wife forays forth into the working world. And wouldn’t you know it? Suddenly everyone is much happier, and the children’s issues start to resolve “all on their own”. But the husband is healing much more fully than at first it was feared. How will this all end, in 1920s’ small town America, where gender roles are by and large carved in granite?

A lovely book, and extremely readable for its keen examination of the marital relationship it portrays, and its touching details of family life and the woes and joys of childhood.

Where it lost its few points with me was in the unlikely perfection of the wife’s experience in the working world; she waltzed right in and was promoted up the department store ladder of responsibility remarkably easily; even allowing for her detail-freak perfectionism her immediate grasp of her new role in life was a bit hard to swallow, as was her sudden relaxation regarding less than stellar household cleanliness. And I was uncomfortable with the “easy” ending, as I mentioned earlier.

I’ve read a number of other Dorothy Canfield Fisher novels, and they share this same occasional over-simplification as the author hammers her point home – she was something of a crusader in the area of improving family life and giving a fuller and freer role to children – but as she is also a marvelous story teller we can allow her this tiny tendency, I think.

************

Of the four books in this grouping, if I were going to recommend one as a should-read, it would definitely be The Home-Maker.

Followed by Christopher and Columbus, because it is utterly charming, if a bit silly in its premises and occasionally rather wordy. The Green Bay Tree is a perfectly acceptable drama, though nothing extraordinary. As for Her Father’s Daughter, consider yourself forewarned!

Read Full Post »