Mamma by Diana Tutton ~ 1955. This edition: Macmillan, 1955. Hardcover. 218 pages.

Mamma by Diana Tutton ~ 1955. This edition: Macmillan, 1955. Hardcover. 218 pages.

My rating: 8.5/10

Remember the buzz a year or so ago here amongst the book bloggers about Diana Tutton’s Guard Your Daughters?

Many people enthused over this forgotten novel by an elusively obscure writer; a few didn’t feel the love. I fell somewhere in the middle of these reactions, for while the book intrigued me I didn’t outright adore it, but it did make me curious about what else this writer could do. I’ve been watching for copies of her only other two books, 1955’s Mamma and 1959’s The Young Ones, for over a year, and lo and behold, I found one recently through an online book dealer. Mamma is now mine.

And what a happy gamble this was – I enjoyed it greatly. I had expected something either brittle or dreary, and possibly a bit smutty, for I knew ahead of time that it concerned a middle-aged mother plotting a love affair with her daughter’s husband – but in reality it is a rather more delicate thing, and well handled, and full of sly humour, and ultimately more than a little heart-rending. It has an intriguing ending as well, which could go any which way, leaving our main character poised on the verge of the next bit of her life.

Where it lost its 1.5 points – for it came close to being a 10 on my personal rating scale – was in its occasional outspoken snobbishness, something which also disturbed me in Guard Your Daughters. And, as in that novel, I am having a hard time deciding whether it is meant to be a tongue-in-cheek joke by the author, or a real reflection of her feelings, putting her thoughts into her character’s heads. It was just frequent and mean-spirited enough to take the bloom off this otherwise highly diverting concoction.

41-year-old widow Joanna Malling has just bought a house in a country village, a rather decrepit, unattractive house, with potential masked by neglectful decay. With her furniture unloaded, Joanna sinks into a momentary depression, wondering what she has done, and wishing desperately that she had someone to lean on, someone like her beloved husband Jack, who had died suddenly in the first year of their happy marriage, leaving the 21-year-old Joanna utterly bereft and a new mother to boot.

That baby, Elizabeth – Libby – is now a young woman herself, and a lovely, competent, and accomplished one. And also newly engaged. For the very day Joanna moves into her new house, a letter arrives from Libby in London announcing her intent to marry Steven Pryde, a career army officer, fifteen years Libby’s elder.

Joanna is apprehensive, wondering if she and Steven will make friends, and her first meeting with him leaves her cold. Stoic and expressionless, Steven is brusque and almost rude, and Joanna is less than impressed. But as she helps the young couple prepare for their wedding, and as Steven starts to show glimpses of manly chivalry, glints of a sense of humour, and a hidden taste for serious poetry, Joanna starts to see what has caught her daughter’s attention. Steven is also self-centered and frequently brusque, and occasionally dismissive of Libby’s interests and whims, though it is obvious that he also deeply admires her and loves her dearly.

Through a series of unplanned-for occurrences, Steven and Libby end up moving into Joanna’s house several months after their marriage, and the inevitable adjustment period of a brand new marriage finds Joanna caught between her beloved daughter and her enigmatic son-in-law.

I found myself sympathizing most ardently with fictional Joanna. Here she is, trying to make the best of things, and striving to keep out of the newlyweds’ way and allow them privacy, while at the same time dealing with the unexpected upsurge of feelings of grief at her own long-ago loss in her own early days of her marriage. After the first stages of grief had passed, the young Joanna had expected that she would meet another man and would remarry; this has not happened. But Joanna is not soured or embittered by this; she has steadfastly gotten on with her life. For twenty years Joanna has competently coped with her widowhood and single parenthood, sublimating her very real emotional (and sexual) needs in caring for her daughter, housework, and serious gardening. It has been an occasionally fragile balance, though, and it is about to tip, with potentially disastrous consequences.

Steven in only six years younger than Joanna, and the two inevitably find common ground in gently humouring just-out-of-her-teens Libby’s occasionally juvenile enthusiasms, heedless pronouncements, and occasional mood swings. Their shared appreciation of literature and poetry leave Libby far behind; she is not by any stretch an intellectual. Constant propinquity allows even stronger feelings to develop, and Joanna is horrified to realize that she is falling in love with her daughter’s husband, while he is watching her with something more than dutiful regard.

When Libby at last realizes that the building tension in the three-person household is not her imagination she blazingly accuses Joanna of attempted seduction, which scenario is very close to the truth. In Joanna’s defense Steven has been allowing himself the same burning glances at his “Mamma”-in-law as she is sending his way, though neither had so far made an overt move to bring their growing mutual attraction to the next stage.

Libby is soothed down and the potentially explosive situation is delicately defused by unspoken agreement between Joanna and Steven. He and Libby move on into their own establishment, but the experience has made Joanna take a deeply introspective look at how closely she allowed herself court disaster. Still a relatively young woman, she must rethink her future and how best to proceed into the second half of her life.

An unusual novel with some mildly unconventional characters. Steven perhaps gets the least authorial attention of the three main protagonists; he remains something of an enigma throughout, despite our glimpses at his secret self. Confident and competent Libby is shown in some detail, though mostly through her mother’s affectionate eyes.

It is Joanna who stands out, and her depiction is sensitive and deeply moving. Having several too-young widowed friends myself, Joanna’s agonizing internal dilemma as to how to best cope with her own needs when all about her prefer to conveniently view her as “beyond all that” strikes true indeed. Joanna has absolutely no one to confide in, and when her own daughter blithely and rather cruelly speculates on the psychological twists of those who are deprived of a satisfactory sex life, without grasping the obvious fact that her own mother is one of those so deprived, we cringe for both of them, but mostly for proud and stoic Joanna.

The gardening references – very important, as Joanna spends a lot of time working away her many frustrations at the end of a trowel – are impeccably plausible; a decided point in favour as this is something I am alert to, and I’ve frequently caught authors out on their lack of detailed horticultural knowledge. Diana Tutton appears to have been a gardener, or at least a garden lover.

Several lower-class characters, namely the two daily helps employed by Joanna, and the unmarried mother-to-be employed as a cook-companion by Steven’s mother, are depicted in the broadest of caricatures and here the Snob Factor again raises its ugly head, leading me to speculate that the dismissive and critical attitude which the upper-class – or, to be more accurate, upper-middle-class – characters show reflects the author’s personal views and is not merely a fictional device. Several scenes concerning these characters degenerate into broad farce; a jarring note in an otherwise well-constructed tale.

That last caveat aside, I’ll repeat that I liked this novel a lot, and am now very keen indeed to get my hands on the third of Diana Tutton’s elusive novels, The Young Ones. Apparently it concerns a woman’s dealing with the incest of her brother and sister. A decidedly eyebrow-raising scenario, but if Mamma is anything to go by, perhaps intriguingly plotted. I’m up for the gamble, but so far have not come across a copy for sale at any price anywhere, despite diligent online searching.

I’ve also been inspired to re-read Guard Your Daughters, and though the annoying bits still make me grit my teeth a bit, I’m enjoying it much more this time round, and may at some point need to revise my review to reflect the second-time-round reading experience.

Back to Mamma, has anyone else read this, and, if so, what did you think? I do believe Simon tackled it at one point, but didn’t write up a review. Any comments most welcome. 🙂

And has anyone come across The Young Ones? And, if so, what’s the word? Worth the hunt?

Read Full Post »

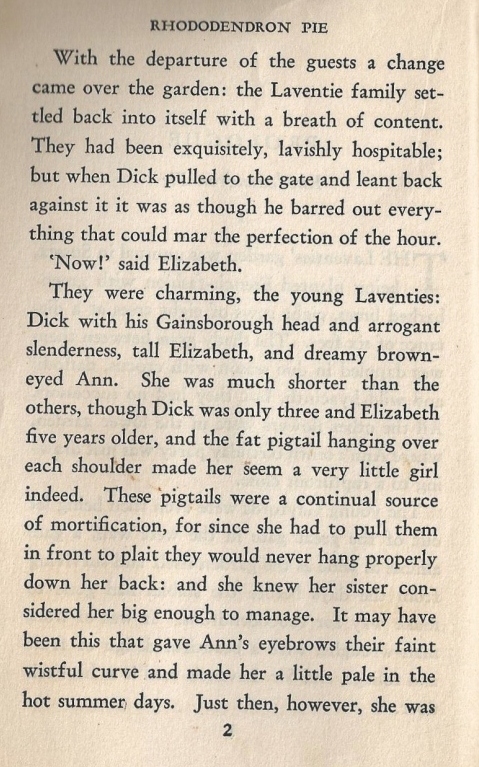

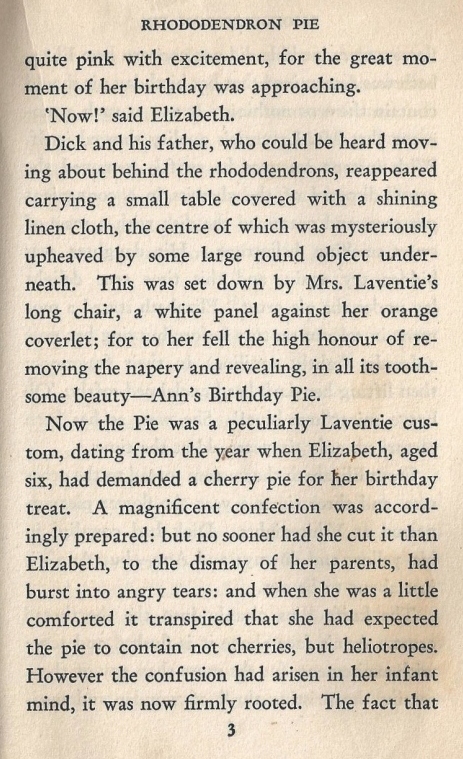

The Sun in Scorpio by Margery Sharp ~ 1965. This edition: Heinemann, 1965. Hardcover. 231 pages.

The Sun in Scorpio by Margery Sharp ~ 1965. This edition: Heinemann, 1965. Hardcover. 231 pages.