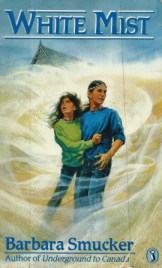

Friendly Gables by Hilda van Stockum ~ 1960. This edition: Viking Press, 1960. Hardcover. 186 pages.

Friendly Gables by Hilda van Stockum ~ 1960. This edition: Viking Press, 1960. Hardcover. 186 pages.

My rating: 6/10.

An average to good example of the vintage juvenile “domestic drama” genre. I’ve happily re-read this book a few times, though if it disappeared from the shelves I wouldn’t be heartbroken, just mildly regretful.

*****

Living in a large house in Montreal, shortly after a move from the United States, the six Mitchell children, Joan, Patsy, Peter, Angela, Timmy, and Catherine, ranging in age from fifteen (Joan) to three (Catherine), are joined by twin brothers. Their mother has had a hard time with the birth, and is weak and confined to bed, so a strict English nurse, Miss Thorpe, is engaged to care for the babies and help run the household until Mother can recover enough to take on her usual role.

There are immediate conflicts. Only Joan finds favour in Miss Thorpe’s eyes as she proves herself both willing and very capable in helping with the babies and taking on much of the meal preparation; but the younger five are considered much too selfish, rambunctious, noisy, messy and careless by the strict nurse. Father is busy working and is seldom home; cash flow is definitely an issue in the household; which though comfortably middle-class is far from wealthy. There is nothing left for any extras after paying Miss Thorpe’s wages, and several plot lines focus on the children trying to earn enough money for various crucial things they need or desire.

The American Mitchells are still adjusting to life in French Canada. The children attend Catholic school, and their struggles with learning a second language, getting along with the Québécois children who occasionally toss a scornful “You Yankee!” their way, and trying to conform to the strict standards of the nuns and priests at their schools are nicely depicted.

The story focuses on each child in turn, while giving a broader picture of the inner workings of the family. The only child not given a starring role is young Catherine; each of the others has some sort of adventure. Joan falls in love, and attends her first dance; Patsy loses her glasses and disgraces herself deeply with the nuns at school in numerous ways; Peter falls afoul of a schoolmate and in the resulting fisticuffs knocks down and smashes a large plaster statue given by an important supporter of the school; Angela gets lost while attending a maple sugaring-off party; Timmy becomes infatuated with a girl at nursery school, and attempts to come up with a perfect gift for her.

Mother eventually gets better, the twins appear to be thriving after the month or so that we are in touch with the family, peace is made with Miss Thorpe, and we leave the family celebrating at the christening party.

*****

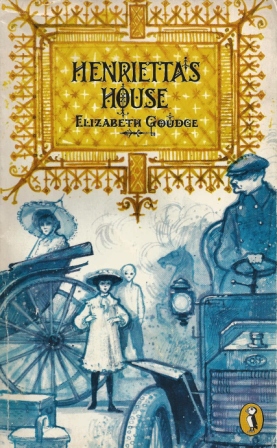

A pleasant though minor story, from an author who then went on to write several more serious and very well-regarded historical fictions set in Holland during World War II – most notably The Borrowed House and The Winged Watchman. Though there are superficial similarities to Elizabeth Enright’s The Saturdays, Friendly Gables does not attain the appeal and overall excellence of Enright’s creation, which defines the genre and deserves every word of its frequent praise.

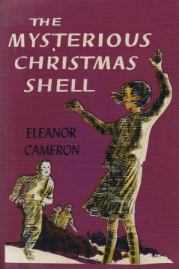

The formula is also much like that of the Eleanor Estes’ Pye Family books in that it mostly relates a family’s daily life, sometimes in microscopic detail. As with the Pyes, the Mitchells are far from perfect, which is pleasantly reassuring to the reader. The morals in Friendly Gables are predictable but not terribly intrusive. And everything always comes out right in the end.

This story does have some lovely vignettes of parent-child and sibling relationships. Something I particularly appreciated was how independent the children were in sorting out their various dilemmas, and how confident the parents were in their children’s abilities to cope. Occasionally a child would go to Mother of Father to report the current happenings, and perhaps ask for assistance or advice (always cheerfully given), but often it was merely to report that the problem was solved, whereupon the parent would basically say “Well done!” and that would be the end of it – no muss, no fuss.

Friendly Gables is the last book in a series of three about the same family, so there are occasional references to off-stage characters and previous happenings, which left me a bit out of the loop, but those would make perfect sense to someone with access to the whole set. It certainly isn’t a big drawback, as the author sketches in enough information to pin it all together.

Friendly Gables is set in urban Montreal, and was preceded by two other novels about the fictional Mitchell family: The Mitchells, published in 1945 and set in Washington, D.C., and Canadian Summer, set in rural Quebec, published in 1948.

These three books are autobiographical, according to both the author and her now-adult children, and were inspired by and record incidents in the very real Marlin family’s life. Hilda van Stockum published her juvenile books and her many illustrations of other authors’ works under her maiden name, but was in her “everyday” life Hilda Marlin: accomplished painter, U.S. Civil Service wife, and dedicated mother of six children, all of whom subsequently attained rewarding and creative careers of their own.

Hilda was born in 1908, in Rotterdam, Holland, to a Dutch father and an Irish mother, and spent her youth in both Holland and Ireland. She attended art school, where she apparently received much praise for her realistic paintings. Hilda married her brother’s college roommate, American Ervin Ross Marlin, in 1932, and travelled with him to New York. The couple and their steadily increasing family lived in various cities in the U.S.A.. They then spent six years in Canada, before moving to Ireland, and eventually to England, where Hilda died peacefully at the age of 98, still living in her own home, in 2006.

Hilda, child and grandchild of scientists, artists, philosophers, writers and intellectuals, was raised in an atheist household, but she embraced the Anglican faith in her teen years, converting to Catholicism in adulthood. Her devout faith appears in her books, including Friendly Gables, but more as a background to the story than in a “preachy” manner.

Hilda van Stockum’s strong belief in the importance of family also permeates her writings, making her a decided favourite of those seeking “wholesome” books to share with their children. A number of her titles are still in print, some more than seventy years after their first publication, so there are still eager readers. Hilda van Stockum’s works seem to be particularly in favour with “traditional” homeschoolers, which is understandable due to the author’s positive views on “family values” and religion. And “secular” readers – do not fear! These books can be enjoyed by all.

I’m including this book in the Canadian Book Challenge because of the Quebec setting, though the author is not Canadian, but Dutch-American, and the family in the story is American. National identities and prejudices play an important role in Friendly Gables; the author handles the topic very well.