Lovers All Untrue by Norah Lofts ~ 1970. This edition: Doubleday, 1970. Hardcover. 252 pages.

Lovers All Untrue by Norah Lofts ~ 1970. This edition: Doubleday, 1970. Hardcover. 252 pages.

My rating: 7.5/10

Well, this was unexpected. And unexpectedly good.

I quite like what this author does when she turns away from the historical romantic fiction and creative biography she was so much better known for, such as her best-selling depiction of Anne Boleyn in The Concubine, and her somewhat sappy retelling of the Nativity in How Far to Bethlehem?, and lets herself go a bit over-the-top into the realm of domestically set macabre fiction. I’m catching glimmers of a Shirley Jackson-like mindset here, and it’s a treat.

Some time ago I read and was surprised and pleased by another of Norah Lofts’ odd little stories, The Little Wax Doll. Lovers All Untrue will definitely join it on the shelf of keepers. And I am wondering what else the prolific author produced in this style. Time for a bit of delving, I think.

The September, 1970 Kirkus Review call this “a lamplit tale of murder and madness in a Victorian doll house”, and goes on to end its spoiler-laden review (which I refuse to link for that reason) with this perfectly apt recommendation: “A fine horrid tale for matronly secret liberationists.” Yes, indeed, to both of those summations.

The well-off, upper-middle-class Draper family resides in respectable Victorian comfort in a slightly cramped but ever-so-appropriately located, furnished and staffed London house, on Alma Street. The family consists of fifty-year-old Papa (head of a nebulous family business in the City; I don’t think we ever do find out what it exactly is that the firm is all about), the slightly younger Mamma, and daughters 17-year-old Marion and 16-ish Ellen.

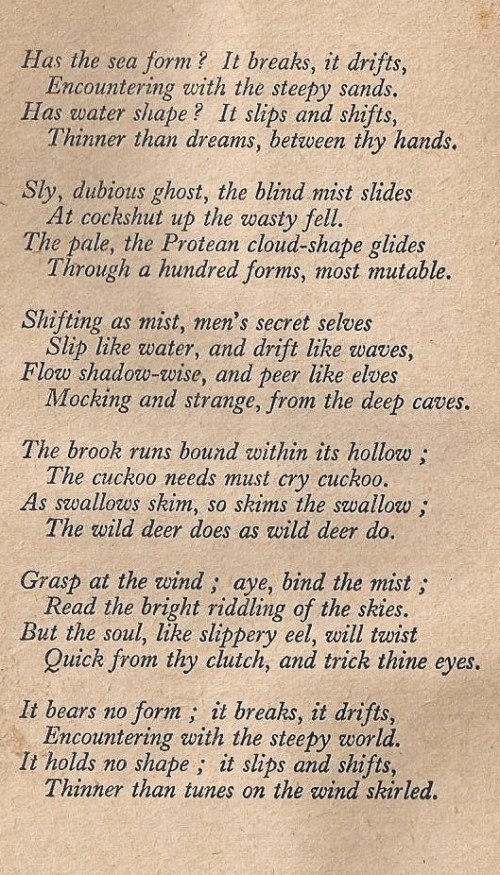

Papa is most decidedly the patriarch of the household, and holds unchangeable views as to the proper conduct of the women of his family. Mamma was once a brilliantly talented pianist, but as her more emotional pieces are unsuitably dramatic in her husband’s opinion, she has been squelched into concentrating her musical skills onto mild drawing-room-acceptable sentimental ballads instead of stormy Lizt concertos. Marion, of considerable intellect, has been abruptly withdrawn from the school where she excelled at academics, because Papa Draper felt that the views of the headmistress were unsuitably liberal in the encouragement of young ladies to consider advanced personal and intellectual development and (fatherly shudder) even careers. Ellen is the smiled-upon child, being peaceful, unambitious, and deeply domestic: the epitome of desirable feminine deportment, in Papa’s eyes.

Papa Draper is a marvelous villain, with absolutely no redeeming features, gloriously secure in his masculine superiority.

Mamma, destroyed herself by her husband’s sheer imperviousness to any sort of female ambition, abandons her daughters to their father’s brutally unimaginative plan for their future: he envisions two devoted (and needless to say unmarried) acolytes to his perpetual male glory, with Marion and Ellen functioning as (sexless) adjuncts to their mother in ensuring that domestic comfort is ceaselessly maintained.

Needless to say, despite Papa’s refusal to countenance such a thing, sex relentlessly enters the picture, with Marion in particular proving deeply passionate beneath her stoic exterior. And even mild Ellen and meek Mamma cherish a few secret desires of their own…

Marion seethes quietly under her repression, and breaks out in the expected way, by acquiring a secret (and decidedly lower class) lover with the expected results. However, events take on some dramatic twists and turns, with Marion showing unexpectedly resourceful attempts to free herself from Papa’s grasp. As Mamma recedes ever deeper into her passive state of non-resistance to Papa’s demands, and Ellen feebly attempts to play peacemaker, Marion finds herself (temporarily) committed to a facility for the mentally troubled, where Papa hopes she will find her outrageously forward impulses tamed.

No one in this oddly mesmerizing tale comes out particularly well; even as the nominal heroine Marion is chock full of too-human flaws, and some of her decisions are decidedly cringe-worthy. So her eventual fate is artistically quite perfect, even though it is rather unexpected. The author was brave in her ending; I applauded her decision to not …well…I’m not going to say what she did here with Marion and Ellen and Mamma. Just that it made me quite satisfied, in multiple ways.

Decidedly feminist themes throughout keep us rooting for the downtrodden women while happily hissing at the stupid, stupid men. Bonus points too for introduction of a scheming lesbian, all done up as another period stereotype just as bizarre as that of Papa’s set piece, whom Lofts has a bit of authorial fun with.

All in all, the author did seem to be rather enjoying herself here, with a good deal of humour glinting out from among the velvety shadows of this mildly horrific, darkish little tale.