Here’s another entry for The 1947 Club. This one doesn’t give any sort of portrait of the year, being strictly inventive historical fiction, but it does have a telling author’s note which serves to highlight the difficulties of the researching writer during wartime.

Apology and Acknowledgement

The irresistible desire to write a book about the nutmeg island of Banda came upon me when I was reading H.W. Ponder’s book, In Javanese Waters. There, in one short chapter, was outlined a romantic, bloodstained history that called for exploration. But, like all exploration, it presented great difficulties. The Dutch East Indies were in Japanese hands, all contact broken; Banda itself is no more than a speck, the size of a fly dirt on the map; no book that came my way gave any idea of the island’s layout. So my geography is the geography of the imagination.

Silver Nutmeg by Norah Lofts ~ 1947. This edition: Doubleday, 1947. Hardcover. 368 pages.

My rating: 4/10

Some centuries ago, in the 1600s, shrewdly businesslike and sensibly adventurous Dutch merchants sailed the southern seas, creating trading empires for themselves in direct competition with their British counterparts. One area both factions set their sights on was the group of tiny island just off Indonesia, on one of which, Banda, grew the world’s only known population of nutmeg trees.

The Dutch having attained possession of the nutmeg isle, they jealously guarded their monopoly. Spice trading being a big deal way back then, the export of fertile nuts or tree seedlings was strictly prohibited, transgression being punishable by imprisonment or worse. Needless to say, some of the Dutch spice plantation owners became fabulously wealthy, and herein lies the nucleus of this absolutely over written story.

(There will now be spoilers galore.)

Two Dutch half brothers, one a wealthy nutmeg plantation owner (Evert), the other a moderately successful sea-captain (Piet), meet on Banda after many years apart.

Says Evert to Piet, “Oh, dear half-brother, good to see you and everything, though we were never very close as children, my mom hating yours and all. Never mind all that, for I am now fantastically wealthy and have progressed so far from our shared childhood as middle class nobodies in Holland. All I need now is a lovely wife to grace my fabulous house. A nice Dutch girl of good family, preferably aristocratic, so I can rub it in to those back home how far I’ve come.”

Says Piet to Evert, “Hey, what about one of the daughters of the Van Goen family? They used to be so high and mighty, scorning our family as not worthy of notice, but they’ve now gone bankrupt. I’ll bet they’d be willing to marry off one of their daughters if one flashed a few guilders their way. Annabet’s a good looker, just seventeen and blond and lovely…”

“Oh, ho!” says Evert. “Just what I’m looking for. Dear half-brother, how about you take this casket of jewels and gold and head back to Holland to convince Mama van Goens to part with her daughter in return for the fixings? You can go ahead and arrange a marriage by proxy for me, and then arrange to ship me my luscious bride.”

Done.

Small problem, however. Lovely Annabet has suffered an illness and is now no longer the beauty she once was, being emaciated and scraggly. Ah, well, the long sea voyage should put her right.

Nope.

Though Annabet proves to have a winning way about her, enslaving other men’s hearts after just a few moments of conversation despite her hideous appearance, proud Evert is instantly appalled. Calling up his pet native fixer, the shady Shal Ahmi, Evert hints that he’d be thrilled if his new wife could be eliminated from the picture.

“No worries”, says Shal Ami. “I’ll get rid of your problem.”

Which he does, by using his many connections to have Annabet massaged and herbal-cured back to her original beauty.

Evert comes home, expecting to find his marriage bed empty, all ready to start anew, and instead finding a tempting beauty in residence. “Oh, wow! My luck is in”, he gloats.

Not so fast, Evert-me-lad. For Annabet has given her heart away to another, and not just any another, but the rogue Englishman who is Evert and Shal Ahmi’s partner in a highly secret nutmeg smuggling scheme.

So that’s the set-up.

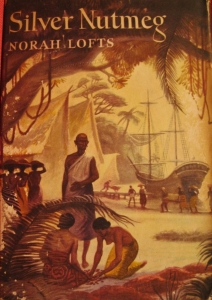

“She learned the meaning of love in a night of murder, lust and terror.” Not quite sure if the possessively groping guy is husband Evert or lover what’s-his-name. That’s quite the foreground image, isn’t it?! Reminds me that I never mentioned the native mistress thing.

It goes on for 368 long, long pages, of heart-wringings and bodice heavings, and sullen scenes, and bitter revenge scenarios, culminating in a bloody native rebellion led by Shal Ahmi, which results in the nasty demises of every single one of the key players, except Piet (remember him?) who sails into the Banda harbour just as Annabet is breathing her last after being knifed by one of Shal Ahmi’s disciples, just after she herself has done in Shal Ahmi with a handily wielded wine bottle.

Husband Evert is also messily dead, as is, presumably, the true love Englishman. (“True love”, though Annabet only actually saw him for a few hours total, with a single stolen kiss their only amorous memory) Can’t remember his name. Maybe it was John? Something like that. He’s offstage for 99.9 percent of the saga, living mostly in Annabet’s head, so we never really get to know him in person.

Norah Lofts could be and frequently was a very good writer, and I find her stuff generally quite entertaining – she had a lovely dark sense of humour and indulged in it on numerous occasions – but this book isn’t one of her winners. On the contrary, it’s truly crappy, because the love stuff is so darned unrealistic that I just couldn’t get my head around it – first sight this, first sight that, unlikely ailments miraculously cured – bah, humbug! – and the historical part is just barely sketched in.

(For those really wish to know, a bit about the real world Banda and the nutmeg trade. It’s truly interesting; I can see why Norah Lofts was intrigued.)

Let’s blame it on the war, and move along, shall we?

Silver Nutmeg had okay sales, most likely (I’m assuming) due to Lofts’ prior bestsellers, in particular Jassy (1944), a very dark, gorgeously crafted gothic-ish novel which does make the cut as far as this reader is concerned. From Kirkus, 1945, with the spoilers removed:

Once again, an experienced period romance as the story of Jassy who lived and loved too much, and was xxxxxx for it in the 19th century, is related by four who knew her. Half gypsy, with an ugly-beautiful fascination, an ungovernable temper, and the gift of second sight, Jassy is first recorded by Barney Heaton, the boy next door; next by a Mrs. Twysdale whose young ladies’ school was to be disrupted by Jassy; next by Dilys Helmar, her friend at that school, who took Jassy home with her to the ruined estate – Mortiboys – and to her amorous, wine-sodden father, Nick… (Lots of plot details removed here.) …Intricately contrived imbroglio, elemental passions for a story that keeps one reading. In the Lady Eleanor Smith tradition.

I’ve also just found a rather lovely post by author Katharine Edgar on Norah Lofts and Why You Should Read Her which I really liked because it pinned down Lofts’ peculiarly unique style most cleverly: The Queen of Gritty, Dark, Agricultural Histfic With Lots And Lots Of Murders.

Yup.

I concur.

I’m pro-Lofts in general, despite the times I want to pitch her books across the room, but I must say you can safely give Silver Nutmeg a miss.

But please do find yourself a copy of Jassy. It’s very available. A candidate for fireside reading these gloomy autumn evenings, with the dead leaves rustling in the cold wind outside…