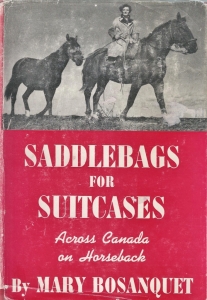

Saddlebags for Suitcases: Across Canada on Horseback by Mary Bosanquet ~ 1942. This edition: McClelland and Stewart, 1942, 4th printing. Hardcover. 247 pages.

Saddlebags for Suitcases: Across Canada on Horseback by Mary Bosanquet ~ 1942. This edition: McClelland and Stewart, 1942, 4th printing. Hardcover. 247 pages.

My rating: 9/10

Every year the Rotary Club in a nearby small city holds a massive, week-long book sale. Every year I come away with boxes of books, and out of these boxes there always emerges at least one or two hidden gems. This year that designation goes, hands down, to this unexpected find.

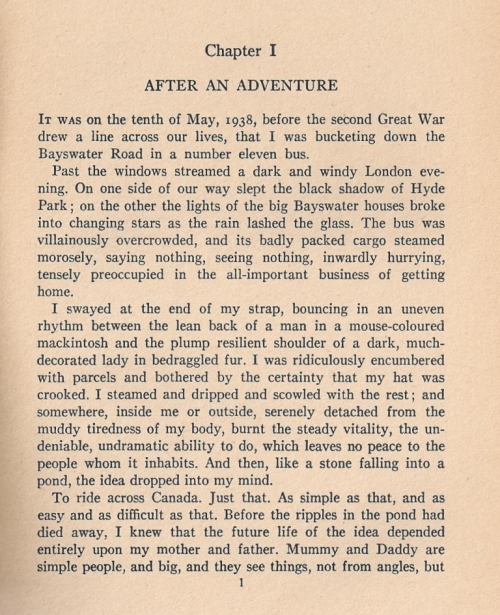

In 1939 a young Englishwoman in her early 20s had an unusual idea, and, being of a straightforward nature and having a methodical sort of mind, set about to see if she could bring the thought into reality.

With the coming war looming on the near horizon, Mary Bosquanet, daughter of a diplomatic family (her father, Vivian Bosanquet, was the British Consul-General in Frankfurt from 1924 to 1932), decided that the time was ripe for a grand enterprise, a heroic self-imposed adventure, to be undertaken before the world erupted once again into widespread conflict. It would be something to remember in the dark days to follow.

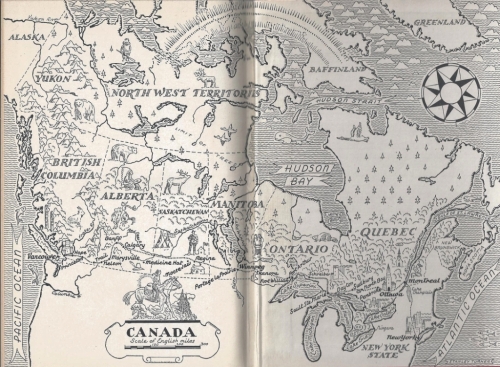

Perhaps inspired by the accounts of Aimé Tschiffely, who from 1925 to 1928 made a 10,000 mile horseback journey from Buenos Aires to New York City, Mary Bosanquet, a lifelong horsewoman and an accomplished rider, decided to try for a relatively more modest but still astoundingly ambitious solo horseback ride: right across Canada from Vancouver heading East.

Mary and her horses Timothy and Jonty achieved the goal, covering an estimated 3800 miles of horse trail, back road, and highway in eighteen months. Of this time, the winter of 1939-40 was spent hosted by a farm family in Ontario. Mary then continued on to Montreal, and then rode south to New York City, where she set sail back to England, to do her part in the war which had indeed broken out shortly after she embarked upon her ride.

The trek was not without setbacks. Mary’s first horse, Timothy, chosen from the working herd of the legendary Douglas Lake Ranch near Kamloops, B.C., started showing symptoms of chronic lameness during the challenging Rocky Mountain crossing from B.C. to Alberta. In Calgary Mary acquired another horse, Jonty, to spell Timothy off, and the trio made it to Ontario together, where Timothy was given an honourable retirement from the trek, finding a less strenuous home where his duties required merely short jaunts versus the pounding day-after-day demands of the long-distance journey. Mary continued on Jonty, and the two rode into New York City on a November day in 1940, escorted by an honour guard of mounted policemen, through Harlem, the Bronx, Central Park and into the Mounted Police Barracks.

Mary herself was injured several times during the ride, first breaking her wrist and later seriously fracturing her arm when she and Jonty were enjoying a wild springtime gallop which ended disastrously when the horse stumbled and Mary was thrown against a tree.

She was the recipient of much attention from newspaper reporters as the trek proceeded, was surprised by several offers of marriage from smitten cowboys, attended the Calgary Stampede and was inspired by the displays there to try out bronc riding herself with reasonably successful results, for though she was unseated several times she felt she had figured out the stick-to-the-horse technique quite nicely, learning through doing, as it were. During the later stage of her journey Mary even visited the Dionne quintuplets, and her wry commentary on that experience is a fascinating glimpse at that particular social phenomenon.

During her winter in Ontario, Mary was astounded to learn that she had been publically labelled as a German spy by the very newspapers which had initially applauded her enterprise. Apparently her unlikely undertaking combined with her frequent picture taking and her fluency in German (remember that she spent a number of years in Germany as the British Consul-General’s daughter) were suddenly seen as highly suspicious. Mary lived those slanders down, but one can tell that the slurs stung; she was already agonizing about not being “home” to help out with the war effort, and she debated ending the trek and heading back to England immediately. Encouraged by friends and family to continue, Mary did so, but ended the Canadian odyssey in Montreal, heading from there into the United States, to New York City, and thence home.

Mary kept a journal throughout the trip, though frequently weeks would pass between entries, for she was in a constant state of physical exhaustion while on the road, and writing up the day’s travels was not a priority. Enough was noted to make a fascinating framework for this account, and Mary’s personal musings embellish the exceedingly realistic account of travelling on horseback, finding a place to settle each night (Mary preferred asking for accommodation at farms and homesteads along the way; occasionally she slept under the stars) and the challenges of feeding both herself and her two horses.

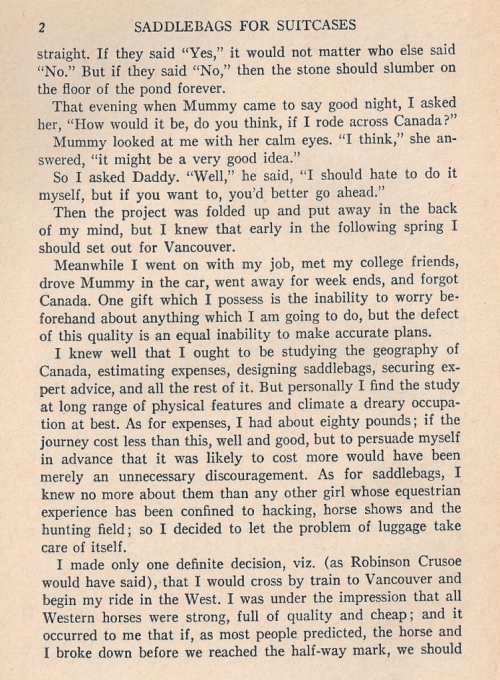

She pulled the enterprise off with a budget of eighty English pounds – the equivalent of about £5000 today, or $9500 Canadian dollars, and, needless to say, relied greatly on the kindness of strangers throughout the trip. (My husband, after reading the book, joked that Mary should be the patron saint of today’s couch surfing travellers – finding constant free or very cheap accommodation for herself plus two equine companions was something of a noteworthy accomplishment all on its own, in his opinion. I hadn’t quite seen it that way, but I quite agree!)

I greatly enjoyed Mary Bosanquet’s account of her journey. She has a self-deprecating but never meek voice, a healthy sense of humour, and strong opinions ably defended. I liked her a whole lot by the end of her journey, enough so that I have sought out and ordered her two later memoirs, 1947’s Journey into a Picture, concerning her post-war social work with the YMCA in Italy after her return from Canada, and 1962’s The Man on the Island, an account of a year spent in Oxford.

Saddlebags for Suitcases is, in general, very competently written, but it has amateurish moments throughout, such as the author’s insistence on sharing her attempts at poetry, which, though adding to the charm of this from-the-heart memoir, also bring forth the lifted eyebrow, because to be quite brutally honest she’s not really much of a poet, except in the talented schoolgirl sense. There are great gaps in the narrative as well – and understandably so! – for one day of riding through Saskatchewan is surely much like another.

I loved the early chapters describing the travels through British Columbia, and the journey through the mountains following trails which have now become the Hope-Princeton highway. The changes between then and now are quite astounding; B.C. readers will love the contrast between the still-rural Fraser Valley of the 1930s and today’s overflow-from-Vancouver smog-shrouded sprawl.

The book is a marvelous bit of Canadiana, and a very telling piece of World War II memorabilia, though the action takes place far from the site of the actual conflict.

Here are the first three pages, for those who think this might be a diverting read. The book is in good supply on ABE, and is available as a print-on-demand book through the Long Riders’ Guild publishing division.