Three quick reads this past few days ran the gamut from slightly-gosh-awful to thoughtfully-affirmative to poignantly-hilarious. All are deeply imbued with sense of place. Light reading, all three, easy to pick up and put down, though I must confess I read each one straight through. Without further ado, here they are.

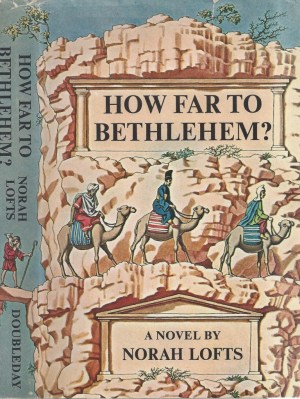

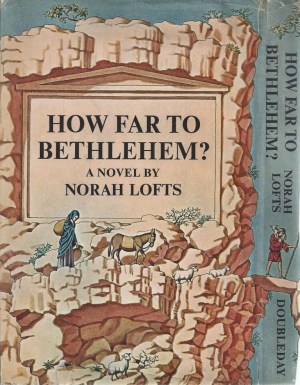

One Happy Moment by Louise Riley ~ 1951.

One Happy Moment by Louise Riley ~ 1951.

This edition: Copp Clark, 1951. Hardcover. 212 pages.

My rating: 4.5/10

I’m glad to have read this obscure Canadian novel, for it made me stop and muse on what makes a style of writing either a hit or a miss with a reader. This one felt awkward to me, stylistically and plot-wise, and even its glowing portrayal of a landscape I have personally known well didn’t quite make up for the clunky prose and the rather cardboard characters. I opened it up prepared to enjoy it; I closed it no longer wondering why this was the author’s only adult novel, and why it (apparently) never made it past that first printing.

She lifted her arms and pulled off her grey felt hat, shaking her head like a young horse, freed from his bridle. She ran to the lakeshore and tossed the hat into the lake, laughing at it as it bobbed primly over the ripples. She tore off the jacket of the grey suit and hesitated about throwing it after the hat. Instead she ran back to her suitcase, snapped it open, and took out a pair of plaid pants and a yellow sweater. Taking a last quick look about her, she pulled down the zipper on her skirt and stepped out of it, kicking it aside. Quickly she unbuttoned her grey blouse and took it off, tossing it on top of the skirt. She pulled her slip over her head and, as she stooped to take off her shoes and stockings, the warm sun felt like a caress on her back. She pulled on yellow knitted socks and heavy shoes. When she was dressed in slacks and yellow sweater, with a scarlet handkerchief knotted around her throat, she pulled the pins out of her fair hair, shook it free, and tied it back with a yellow ribbon.

And in case you didn’t quite catch the symbolism, there’s more.

Into the suitcase Deborah shoved the clothes she had taken off, added a few rocks, hauled the suitcase to the shore, and tossed it into the lake. She watched it sink. Her hat had floated several yards away from the shore, and she waved good-bye to it. Then, slinging her rucksack onto her back, she looked for the path up the mountain side.

The young woman so anxious to dispose of her city clothes – and, by inference, her dull, grey, prim and proper former life – is one Deborah Blair, and she’s about to hike nine miles up a trail to a tourist camp somewhere between Lake Louise and Lake O’Hara, on the Alberta side of the Rocky Mountains.

Her first encounter with another person is an old man just up the trail; he pops out of the bush, startling her greatly, and then proceeds to tell her that he knows she is running away from something, and that she is like a young doe, “…frightened…by a hunter, maybe, out of danger now, taking time to be proud of her speed and to taste her freedom, but still wary, remembering her fright…”

But the mountains will give her sanctuary, he goes on to say, and Deborah parts from him, mulling over what he has said, rehearsing her new role in preparation for meeting her fellow guest camp residents.

These are a motley crew indeed. Evangeline Roseberry is her hostess, an uninhibited, provocative and sultry woman of a certain age. Young ranch hand Slim appears to be very close indeed to his employer, and when Slim is not in attendance the male guests are often to be found in “Vangie’s” cozy cabin. Middle-aged Dr. Thornton is holidaying without his wife and apparently finding his hostess a suitable substitute; downtrodden Mr. Nelson is at the beck and call of his own formidable wife, though he glances hopefully at Vangie’s lush charms when Mrs. Nelson’s focussed gaze is elsewhere, and teenage Sue Nelson cherishes a passion for handsome, red-haired, flashing-eyed yet taciturn geologist Ben Kerfoot. In the kitchen brusque Mrs. Horton reigns supreme, dispensing pithy criticisms to all and sundry along with the bacon and eggs.

Deborah gravitates toward avuncular Dr. Thornton, as nosy Mrs Nelson attempts to probe into “Mrs. Blair’s” past, which appears to be decidedly mysterious, especially when an RCMP officer appears asking questions about why a suitcase with the initials D.B. was found floating in the lake at the bottom of the trail. The plot thickens, with heaving bosoms and flashing eyes from the female contingent all round, and lusty glances and/or darkly passionate glares from the men.

One after another, the people from whom Deborah seeks to hide track her down to her mountain fastness, but she gains strength from the purity of the air and the pristine beauty of the surrounding peaks – not to mention Mrs. Horton’s hearty cooking – and stands up for herself at long last.

Though this novel started out promisingly enough, but ultimately didn’t take me where I hoped it would, and most of that was the fault of the writing, and the lack of a cohesive plot.

Deborah’s vaporings are overplayed, and her flip-flopping between men left me bemused. She is decidedly attracted to both Dr. Thornton and Ben-the-geologist, who in turn steal embraces from whichever woman is present and willing, and, when a manipulative cad from her past appears she mulls over throwing her lot in with his, before the mountain breezes blow some sense into her head. An über-controlling mother appears and is finally confounded, and Deborah prepares to set her sights on making her fortune in Vancouver, being as far away across the continent as she can get from her previous life as a meek librarian in Montreal.

The author was a Calgary librarian and storyteller, and her work with children resulted in the naming of a library branch after her in her native city; the wealthy Riley family was well-known for their philanthropy and social conscience, and Louise by all reports was a fervent advocate for childhood literacy.

Four of Louise Riley’s books were published between 1950 and 1960, the juveniles The Mystery Horse, Train for Tiger Lily, and A Spell at Scoggin’s Crossing, as well as her only adult book, One Happy Moment. Though Train for Tiger Lily received the Canadian Library Association Children’s Book of the Year Award in 1954, a quick glance into my standard go-to children’s literature reference, Sheila Egoff’s Republic of Childhood, finds that perceptive literary critic dismissing Louise Riley’s juveniles as “insipid and contrived”, which I can sympathise with after reading One Happy Moment. Interesting though it may be in a vintage aspect, this is not in any way inspired writing.

Worth taking a look at is the commentary at Lily Oak Books , where I first heard of One Happy Moment. Lee-Anne’s review is well-considered and thoughtful, and she includes some gorgeous pictures.

My copy of the book is going on the probation shelf; I’ll share it with my mom and then decide if it gets to stay or go. The attractive dust jacket will likely tip the balance. As it arrived in fragile shape, I went ahead and put it into Brodart, and its vintage appeal might be too tempting for me to part with, though the words inside the book are not of the highest rank.

A Big Storm Knocked It Over by Laurie Colwin ~ 1993.

A Big Storm Knocked It Over by Laurie Colwin ~ 1993.

This edition: Harper Collins, 1993. Softcover. ISBN: 0-06-092546-9. 259 pages.

My rating: 7/10

Moving right along to the other side of the continent and New England, for this gentle yet slyly cunning novel about love and friendship and transcending unhappy childhoods. It’s also about the terrifying act of bringing a child into the world, and an ode to the possibility of happiness, and our right to seek such out in an often unhappy world.

Does that sound impossibly twee and gaggingly chick lit? Well, it isn’t. (Okay, maybe just the tiniest bit. But it’s easy to get past. I liked this book.)

One Happy Moment has a stellar cover and ho-hum contents; A Big Storm Knocked It Over has a dreadful cover and a well-written inside. Ironically, for the protagonist of Big Storm is a graphic designer employed in the book trade, the blandness of the exterior presentation would not normally have received a second glance from me but for my previous encounter with this author. The late Laurie Colwin – she died suddenly in 1992, before this book was published – was a much-loved columnist for Gourmet magazine and a bestselling cookbook author, novelist and short story writer. Big Storm was her fifth and last novel.

My first acquaintance with her was some twenty years ago, through Goodbye Without Leaving, about a white ex-backup singer for a black pop band – the token “White Ronette” on the tour bus – and her life after music. I read it just after my son was born, and it struck very close to home; Colwin perfectly captured that “now what?” atmosphere of the ultimate personal change of new motherhood and walking away from your past you, and I was comforted by the parallels between her fictional world and my own. It was also very funny.

In Big Storm, Jane Louise has just married her live-in boyfriend Teddy, and is surprised to find that marriage does indeed change things, even if all that is different is a piece of paper and a ring. We are introduced to an ever-widening circle of co-workers, friends and family, and watch with only slightly bated breath as Jane and Teddy find their new groove.

The gist of the novel is that sometimes family is rotten bad, but that you can always choose your friends. And that babies are quite amazing. And yes, life is terrifying, but if you can find someone to love, who also loves you, it still isn’t all shiny sparkly perfect, but it helps.

I don’t know what else to say. It was good. Not great, but definitely good. And there was a fair bit of to-ing and fro-ing from the countryside to the city, and a lot of emphasis is placed on where you’re from and ancestral homes and the clannishness of small New England towns, so I figure it counts in my vaguely themed geographical surroundings thing I’ve got going in this post.

Laurie Colwin was an interesting person and a more-than-just-good writer. I still feel sad when I think about her too-soon departure from our world.

Mama Makes Up Her Mind, and Other Dangers of Southern Living by Bailey White ~ 1993.

Mama Makes Up Her Mind, and Other Dangers of Southern Living by Bailey White ~ 1993.

This edition: Addison Wesley, 1993. Hardcover. ISBN: 0-201-63295-o. 230 pages.

My rating: 9.5/10

The best is last, and what an unexpected book this turned out to be. I had picked it up along with a random selection of others at the Sally Ann one day, thinking it was a light novel suitable for dropping off with my mom for her entertainment, but not really intending to read it myself. (It reminded me of something by Fannie Flagg, from the title and the cover illustration and the blurbs about “absolute delight” and “like sitting on a porch swing.” Look away! my inner voice chirped, because I have to confess that Fannie Flag leaves me utterly cold, though Mom can handle her in well-spaced intervals.)

My husband was between books, picked it up off the stack by the door and chortled his way through it before pressing it on me. I sat down with it over dinner, and looked up two hours later after having read it through in one continuous session. Easy as picking daisies to prance through, this one was. And I must say a laugh or two escaped me as well.

This turned out to be a collection of short – some very short – anecdotes and vignettes, many centered on White’s mother, the “Mama” of the title, and others more concerned with Bailey White herself. They were originally presented on NPR in the United States, with the author reading her own pieces, but they work exceedingly well in print.

Bailey White was born in 1950 and still lives in her rural family home in Thomasville, Georgia. Until her mother’s death at the age of 80 in 1994, the two were close companions. Their joint adventures as “a widow and a spinster” are the focus of some of these lively vignettes, but Bailey White’s scope is wide and she draws inspiration from a vast range of experiences. Bailey White worked as a Grade One teacher for over twenty years in the Thomasville school she herself attended as child, after returning to Georgia when her eleven-year-old California marriage ended in 1984.

Between the covers of this delectable smorgasbord of a book you will find tales of an antique spyglass, the best movie ever made (Midnight Cowboy, according to Mama), Road Kill (and how to decide if it’s edible), Pictures Not of Cows, an Armageddon of a storm and how prayer proved not all that useful, feral swans, an alligator which bellowed on cue, snakes lethal and benign, Great Big Spiders, the perfect wildflower meadow, how to travel unmolested by men (involving a maternity dress and a fake wedding ring), D.H. Lawrence as a life-saving substitute for The Holy Bible, and tales from the classroom.

And much, much more. Something like fifty little stories are stuffed into this book, and they are, without exception, quite excellent.

Apparently based on real people and incidents, there is likely a bit of embellishment to some of these; they have the well-polished feel of anecdotes often told, but that in no way lessens their deep charm.

Passionate, deeply revealing, kind, maliciously humorous – all of these can and do describe the author’s voice. Loved this.

And to think I almost missed it!

A great quick read for the bedside table, or to tuck into a pocket for a waiting room stint. Or to read at coffee break, or over a solitary lunch. Watch out for those spontaneous moments of glee, though. You might get some odd looks. (Or even get in trouble with your beverage.)