Dear Dodie: The Life of Dodie Smith by Valerie Grove ~ 1996. This edition: Chatto & Windus, 1996. Hardcover. ISBN: 0-7011-5753-4. 339 pages.

Dear Dodie: The Life of Dodie Smith by Valerie Grove ~ 1996. This edition: Chatto & Windus, 1996. Hardcover. ISBN: 0-7011-5753-4. 339 pages.

My rating: 7.5/10

I wonder if I can be truly fair to this biography, reading it as I did back-to-back with the subject’s own long and detailed discourse on her life?

For though Valerie Grove had complete access to the complete archive of Dodie Smith’s personal papers, the outline of Dodie’s life and the anecdotes she shared are merely repeated ad lib from Dodie Smith’s own four volumes of memoir in the first three-quarters or so of the book. Here and there Valerie Grove gives clarification and snippets of background information, but in essence what I felt I was reading was a brief condensation of the original memoir, minus the personal touches and the strongly “I” point-of-view which brought Dodie’s much longer work to life.

I was eager to get to the years not covered by Dodie’s own memoirs, the years after her return to England after her long American hiatus (1938 to 1953) originally inspired by partner Alec Beesley’s conscientious objector convictions and their apprehension about how he would be treated as England entered into the war years.

Valerie Grove did fill in the blanks here, as she was able to glean many of her facts from the completed manuscript of Dodie Smith’s fifth and unpublished volume of memoir, as well as from personal interviews with those who knew Dodie Smith well in her final years.

It is rather tragic that each successive volume of memoir had a harder time finding a publisher, as Dodie’s literary and theatrical star status waned with each succeeding decade and the predictable shift in public tastes and the ongoing hype around fresh young talents, such as Dodie herself was way back in the 1930s with her play-writing successes starting with Autumn Crocus and ending (to all intents and purposes, as she never after this wrote another really successful play) with Dear Octopus, and, to a secondary extent, with her two successful literary efforts, I Capture the Castle, and The Hundred and One Dalmatians. While her other titles had respectable sales, due in great part to the reputation of Dodie Smith’s “great” books, none were anything like as successful as those first two forays into mainstream and juvenile fiction writing.

Grove provides more details of Dodie and Alec’s rather unique-for-the-time household – the relationship, formalized by a 1938 marriage ceremony, was a perfect example of role reversal, Dodie being the breadwinner and Alec the support system and domestic homemaker. Neither Dodie nor Alec expressed any desire to have children, though both reportedly enjoyed the company of other people’s offspring; their affections were concentrated on each other and on their beloved pets.

Alec was tremendously handsome, in a matinee idol sort of way, and though occasionally encouraged to consider taking a screen test, he calmly declined any attempt to share the limelight with Dodie, living what seems by all accounts to be a rather self-contained and contented life. There was speculation among their peers (and I must admit to this as well) whether Alec Beesley was in fact gay, as it was public knowledge that he and the 7-years-older Dodie had separate bedrooms, and were intimate friends with a number of rather openly gay or bisexual men, most prominently perhaps the writer Christopher Isherwood.

Grove agrees with the contention that Alec was indeed “straight” in regards to sexual matters, and utterly faithful to Dodie. She herself, after a young womanhood filled with sexual exploits, also seemed content to spend her later years in happy monogamy, stating at one point that her sexual urges seemed to have almost completely disappeared after the indulgences of her earlier days.

Dodie’s return to England in the early 1950s was at first marked by her exhilaration at being back home – her years in the United States were never completely happy, as she suffered from continual homesickness and guilt at abandoning her home country in time of war – and then by a rising sense of anguish at the realization that her plays, which she continued to write and attempt to promote, were no longer to the public taste. From “Dodie Smith” being a name to pique keen interest with theatrical managements, her name on a play was now a detriment, as the trend was now to bleak hyper-realism versus Dodie’s domestic “cozies”.

Further attempts at fiction writing after the stellar success of I Capture the Castle were not very successful; two more children’s stories following the also-stunningly-successful The Hundred and One Dalmatians also failed to capture the public imagination. Dodie and Alec, always living well up to their substantial income, started having serious money concerns. Royalties from the successful Disney adaptation of Dalmatians were to prove their most reliable source of steady revenue, though this declined as the years passed.

Dodie and Alec spent their last years in virtual seclusion in their country cottage, Dodie obsessively working on her memoirs, and Alec devoting himself to gardening. As age began to take its physical toll, things became increasingly difficult. Money worries, difficulties finding domestic help, and a succession of illnesses and injuries began to take precedence over Dodie’s creative efforts, though she remained remarkably lucid and articulate to the end, giving occasional interviews and writing letters and editing her journals and manuscripts.

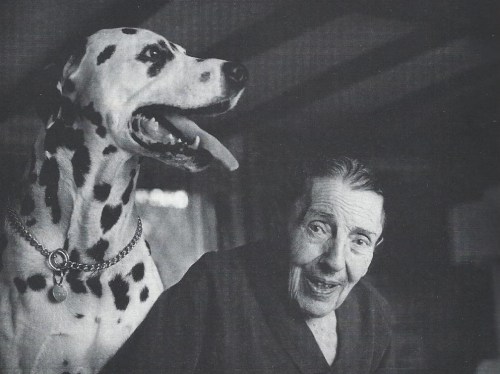

One last Dalmatian, Charley, was Dodie’s constant companion, becoming even more important to her psychological well-being after Alec’s sudden death in 1987. Dodie had always assumed that Alec would outlive her; she was cut adrift to a great degree by his loss, suddenly having to deal with the multitude of small household and managerial tasks which he had always sheltered her from. Boisterous Charley gave Dodie an outlet for her affections, but was actually something of a challenge to care for; reports by those who knew her in her last years remarked on how bumptious he was, and how he would continually knock tiny, increasingly frail Dodie down. But she loved him unconditionally, setting aside a sum of money in her will for his care in the event of her death.

Living alone in her cottage, now bedridden and increasingly fragile, Dodie protested against leaving, hoping that she could die in her own bed with Charley by her side. Her doctor insisted upon her entry into a nursing home, as it was becoming impossible to provide the needed care at home. Dodie Smith died in that nursing home in November of 1990. Charley, left at the cottage with daily visits by a caretaker to feed him, went into a decline, and died three weeks after Dodie’s departure.

Dodie Smith’s life was in some senses stranger than the fiction she made out of it; the “best bits” in her successes were taken directly from her life. A most unusual personality, admired greatly by many, loved deeply by some, and despised as well by those she fell afoul of. Dodie Smith had a very substantial ego; she had a stout faith in her own creative abilities, and though she occasional poked rueful fun at herself, one feels that she never really believed that she could possibly be wrong.

Valerie Grove has written a biography which shows all of the facets of Dodie’s personality. Borrowing heavily from Dodie’s own memoirs, its one major flaw in my opinion is that it is too dependent on these and on the continual quotations from the Look Back with… books. Having just read the books, much of what Grove wrote was very repetitive. Where she did cover new ground, there was occasionally a lack of context, as it seemed as though Valerie Grove was speaking to herself rather than to her audience.

Dodie Smith’s memoirs are very strong stuff. She has a distinctive voice which overwhelms the reader and draws one in and makes it hard to break away. I wonder if Valerie Grove felt the same way, which might account for the occasional flatness of the bits which diverge from Dodie’s account.

While one feels that Grove truly admires Dodie’s accomplishments, she is also just the smallest bit sour towards her subject. She seems to delight in pointing out the oddities of Dodie’s personal appearance, and continual physical descriptions of Dodie in her very old age seem a mite mean-spirited – “a wizened prune in a mink coat”, “a squeaky-voiced gnome”, “her stomach stuck out, possibly making up for her behind which had disappeared altogether” – and these are just a few of the many references throughout the biography to Dodie’s “odd” physique.

By all means read this biography; it does give a good overview of the life of Dodie Smith. But if at all possible, one should balance it by reading the subject’s own description of her life, because after reading Dodie’s memoirs I liked her an awful lot – she rather won me over with her balance of supreme ego and self-deprecating irony – and after reading Valerie Grove’s study I detected a certain sourness regarding her subject which tinged the writer’s expressed admiration with just a shade of doubt as to Grove’s real feelings regarding Dodie Smith.

Dodie Smith was a terrifically complex woman inspiring equally complex emotions even after her demise, is my very final summation of this biography which caps off my own readerly examination of this remarkable (and remarkably individualistic) woman’s life.

All in all, a worthwhile read. Recommended.

Our heroine is writing this account in her “Honeymoon Diary” – a gift from one of the bridesmaids, a blank book intended to document the joys of the first nuptial excursion. Instead it is being used to record the reasons behind the bride’s refusal to go through with things – albeit just an hour or two later than the usual cold-feet-at-the-altar cut-and-run.

Our heroine is writing this account in her “Honeymoon Diary” – a gift from one of the bridesmaids, a blank book intended to document the joys of the first nuptial excursion. Instead it is being used to record the reasons behind the bride’s refusal to go through with things – albeit just an hour or two later than the usual cold-feet-at-the-altar cut-and-run.

Winging It Over Africa and the Atlantic; Hurricanes and Foolish Pride; Sally Bowles (and Others) in Berlin; A Waif in War-Torn France

August 22, 2014 by leavesandpages

I’m pushing forward with the Century of Books project and am attempting to clear the decks – or would that be the desk? – for the next four and a half months’ strategic reading and reviewing, so these four books from the last month or two are getting the mini-review treatment. All deserve full posts of their own; I may well revisit them in future years. Though in the case of the three most well-known, Christopher Isherwood’s Goodbye to Berlin, Beryl Markham’s West with the Night, and Marganita Laski’s Little Boy Lost, there has already been abundant discussion regarding their merits and literary and historical context. I might just concentrate my future efforts on the most obscure of these particular four, Christopher La Farge’s The Sudden Guest, which I have earmarked for a definite re-read.

My rating: 9.5/10

In a word: Lyrical

Beryl Markham was born in England and moved to Kenya with her parents when she was 4 years old. Her mother soon had enough of colonial life and returned to England. Small Beryl remained with her father, and grew up in a largely masculine atmosphere made up of her father’s aristocratic compatriots, visiting big game hunters, and the native farm workers and independent tribesmen.

A highly skilled horsewoman, Beryl became a licensed racehorse trainer in Nairobi at the age of 17, after her father’s farm was wiped out during a severe drought, and he gave her the choice of accompanying him to South America for a fresh start, or staying in Africa to go it alone.

Beryl chose Africa, this time and, ultimately, forever more, dying there in 1986 at the age of 84, still staunchly independent, still very much on her game.

Beryl Markham was introduced to flying by her friend and mentor Tom Black, and took to the air with the same innate skill as she dealt with horses. She eventually concentrated strictly on flying, working as a contract pilot in East Africa, and hobnobbing with the famous (notorious?) aristocratic expatriates making homes and lives in Kenya during the 1920s and 30s, including Karen Blixen, Karen’s lover Denys Finch-Hatton (whom Beryl had her own affair with), Baron Blixen himself (Beryl was his pilot during scouting trips for wild game), and others of that large-living “set”.

In 1936 Beryl set out to attempt a solo flight over the Atlantic, from England to New York. She only just made it across, as an iced-up fuel line forced her crash landing in a bog on Cape Breton. The semi-successful attempt brought Beryl Markham much fame; she continued on with her flying career, though she ended her days once again training African racehorses.

In 1942 West with the Night was published, to much acclaim. It is a memoir made up of chapter-length vignettes of Beryl’s childhood and her experiences with horses, and, most beautifully described, her experiences in the air, including an account of the Atlantic flight. The language is both elegant and heartfelt; I used the term “lyrical” to sum up this book, and that is exactly what this is. Really a stellar piece of work.

There has been much speculation as to who really wrote this book. Many have theorized that Beryl had at least some help with it. Her third husband, Raoul Schumacher, was a journalist who also worked as a ghostwriter; the noted aviator and writer Antoine de Saint Exupéry, another of Beryl’s lovers, had a similar writing style. No one knows for sure, as Beryl firmly maintained that the work was completely her own, though her compatriots were stunned when the book came out as they had never known Beryl to be anything of a writer, and she never produced anything after 1942’s West with the Night.

No matter. This is an elegant bit of memoir, well worth reading for the beauty of its prose, and for the portrait it paints of its twin subjects: the truly unique Beryl Markham and her lifelong strongest love, Africa.

My rating: 7/10 for this first encounter, quite likely to be raised on a re-read.

In a phrase: Bitter musings of a self-centered spinster

Oh, golly, where to start with this one. I can’t quite remember where I got it; likely from Baker Books in Hope, B.C. I remember leafing through it in a bookstore, hesitating, and then deciding it was worth a gamble. Another small triumph of bookish good luck, as it is an intriguing thing, and well worth reading.

It is autumn of 1944, and sixty-year-old Miss Leckton maintains a summer house on the Rhode Island shore; her primary home is her New York apartment. Living alone except for a middle-aged married couple who caretake for her, and a daily housekeeper, Miss Leckton has much time to spend in introspection, and what a lot of self-centered opinions she has assembled, to be sure.

Miss Leckton is supremely selfish and egotistical. She has cast off her closest relative, her niece Leah, due to Leah’s engagement to a young Jewish man. For Miss Leckton hates the Jews. (She muses that Hitler, for all his undoubted faults, has the right idea about suppressing them.) She doesn’t think much of the Negroes, either, which makes thing a tiny bit awkward as her resident married couple, the Potters, are black. The local Rhode Islanders are beneath her notice, mere country bumpkins. One actually has a hard time identifying whom exactly Miss Leckton identifies with herself; she is that uncommon creature, “an island unto herself”, to paraphrase John Donne, who doesn’t appear to want or need anyone, and is steadfast in her self-superiority to everyone around her.

Now a hurricane is reported to be blowing in , and Miss Leckton is reluctantly preparing to batten down the hatches, so to speak, though she persists in thinking that the radio reports are over-hysterical. For hasn’t Rhode Island just barely recovered from a brutal storm, the hurricane of 1938? Another just wouldn’t be fair…

I will turn you over to the Kirkus review of 1946, which is quite a good summation of the style of The Sudden Guest, though the comparison to Rumer Godden’s Take Three Tenses is not entirely accurate, in my opinion. There are enough similarities in technique to let it stand, though.

I searched online for more mention of this unusual and well-written novel and found a really good review, including a creative analysis of what Christopher La Farge was really going on about – the American isolationism prior to the U.S.A.’s entry into World War II, and, to a lesser degree, Miss Leckton’s denial of her own “homoerotic feelings”. Check it out, at Relative Esoterica.

Check out this vintage cover: “Bohemian Life in a Wicked City”

Goodbye to Berlin by Christopher Isherwood ~ 1945. This edition: Signet, 1956. Paperback. 168 pages.

My rating: 10/10

Oh gosh. This was so good. So very, very good.

Why haven’t I read this before?

Perhaps because I have always associated it with the stage and film musicals titled, variously, I am a Camera and Cabaret (cue Liza Minnelli) which were inspired by the book, or rather by one episode early on featuring teenage not-very-good nightclub singer Sally Bowles and her apparent intention of sleeping with every man she comes across whom she thinks might possibly become a permanent patron.

But this book goes far beyond the tale of Sally Bowles, memorable though she is with her young-old jaded naivety and her chipped green nail polish and her heart-rending abortion scene.

Christopher Isherwood has fictionalized his own experience as an aspiring writer in 1930s’ Germany, where he made a sketchy sort of living teaching English to respectable young ladies while spending his free time hanging out with (and observing and recording the goings-on of) the artsy crowd and the cabaret performers and patrons of Berlin’s hectically gay (in every sense of both words) theatre and entertainment district.

Goodbye to Berlin is superbly written, deeply melancholy at its core, and only occasionally sexy. It’s a rather cerebral thing, thoughtful as well as charming and deeply disturbing, picturing as it does Berlin between the wars and the numerous characters doomed to all sorts of sad fates – at their own hands as much as through falling afoul of the Nazi street patrollers.

Am I making Goodbye to Berlin seem gloomy? I hope not, because it isn’t. It is poignant, it is funny, it is occasionally tragic, but it is never dull, never gloomy. And Isherwood’s Sally Bowles – who is really something of a bit player in Goodbye to Berlin, appearing only in one episode of these linked vignettes – is a much different creature than that portrayed on stage and film.

The internet is seething with reviews of Goodbye to Berlin, if this very meager description makes you curious for more.

Christopher Isherwood, I apologize for my previous neglect. And I’m going to read much more by you in the future. This was excellent.

A must-read.

(Says me.)

My rating: 7.5/10

My feeling after reading: Conflicted

I had such high hopes for this novel, and for the most part they were met, but there was just a little something that didn’t sit quite right. Perhaps it was the ending, which I will not foreclose, merely to say that I thought the author could have held back the final episode which provides “proof” of the identity/non-identity of the lost child. It felt superfluous, as if Laski did not trust the reader decide for oneself what the “truth” was. Or, perhaps, to go forward not quite sure of that identity. Knowing one way or the other changed everything, to me, and oddly lessened the impact of what had gone on before.

Most mysterious I am sure this musing seems to those of you who have not already read this novel; those who have will know what I am going on about.

In the early days of World War II a British officer marries a Frenchwoman. A child is born, the Englishman must leave; the child and his mother stay in France. In 1942 the child’s mother, who is working with the Resistance, is killed by the Gestapo. The child is supposed to have been taken to safety by another young woman; on Christmas Day of 1943 the father learns that his son has been somehow lost; no one knows where the baby has been taken.

In 1945, with the war finally over, the father returns to France to seek out his child, whom he remembers only as a newborn infant. A child has been located who may be the lost John – “Jean” – but how can one be sure?

Well written, with nicely-maintained suspense and enough verisimilitude in the reactions of would-be father and might-be son to keep one fully engaged. I will need to re-read this one; perhaps I will come to feel that the author’s approach to the ending is artistically good, though my response this first time round was wary.

Interesting review here, at Stuck-in-a-Book; be sure to read the comments. No spoilers, which is beautifully courteous of everyone. 🙂 I must admit that my own easily-suppressed tears were those of annoyance at the last few lines, as I thought they weakened what had gone before.

But on the other hand…

You will just have to read it for yourself. And you really don’t want to know the ending before you read it; the suspense is what makes this one work so well.

Posted in 1940s, Century of Books - 2014, Isherwood, Christopher, La Farge, Christopher, Laski, Marghanita, Markham, Beryl, Read in 2014 | Tagged Century of Books 2014, Dramatic Fiction, Goodbye to Berlin, Isherwood, Christopher, La Farge, Christopher, Laski, Marghanita, Little Boy Lost, Markham, Beryl, Memoir, Social Commentary, The Sudden Guest, Vintage, West with the Night | 18 Comments »