Ringing the Changes: An Autobiography by Mazo de la Roche ~ 1957. This edition: Macmillan, 1957. First Canadian Edition. Hardcover. 304 pages.

Ringing the Changes: An Autobiography by Mazo de la Roche ~ 1957. This edition: Macmillan, 1957. First Canadian Edition. Hardcover. 304 pages.

My rating: 9/10. What a fascinating autobiography! It was definitely readable, and full of vivid vignettes, capably portrayed.

But is it factual? Perhaps not particularly, from what I’ve found out in some very desultory online research. It is very much a created portrait rather than a true glimpse into what made its subject tick. Nonetheless, I found it a compelling read and I will be approaching my future reading of the author’s works with this self-portrait very much in mind.

*****

First, some background information for those of you (and I suspect there may be some) who have no idea who Mazo de a Roche was, and why I’m finding her story so interesting. Feel free to skip this section; my response to the autobiography itself follows at the bottom of the post. I’ve spent a fair bit of time this past few days doing something of a mini-study on de la Roche; I’m not at all what one would call a fan, though I’ve read a few of her books in the past, without feeling the urge to read everything the author has written. She’s not quite my thing, though I’m intending to explore her fiction more in the future, nudged on by the new knowledge I’ve just gained. An intriguing woman.

Mazo de la Roche was born in Ontario in 1879, the only child of parents who, while not exactly poverty-stricken, certainly experienced ongoing financial difficulties. Young Mazo was a self-described eccentric child, and an avid reader. She created an imaginary world peopled by invented characters which she referred to in her autobiography as “The Play”, and this world, expanded and lovingly detailed as the years went on, is thought to be at least partially the basis of de la Roche’s eventual epic sixteen-book series about a fictional Ontario family, the Whiteoaks, and their home estate, Jalna.

When Mazo was seven years old, her parents adopted her younger cousin Caroline, and the two became as close as sisters – and in some ways perhaps closer. Their intimate relationship was to persist until Mazo’s death in 1961. The young girls shared in the imaginary world originally created by Mazo, and as they grew up they built a shared life which seemed to preclude either of them marrying or living independently of the other for more than brief periods of time. Mazo had written stories and poetry throughout her life, but her ongoing bouts of ill health and the need to care for her invalid mother prevented her from spending as much time writing as she desired to. Caroline became the breadwinner of the family group, while Mazo stayed at home, nursed her mother, and wrote in her spare time.

Mazo had had some success selling occasional short stories to magazines, but her first real literary break came with the publication of a series of linked anecdotal stories, Explorers of the Dawn, in 1922. Mazo de la Roche was at that point forty-four years old, and her greater success was yet to come. Explorers of the Dawn made it onto bestseller lists of its time, alongside The Beautiful and Damned by F. Scott Fitzgerald and Louis Hémon’s Maria Chapdelaine. A foreword by Christopher Morley (best known nowadays for his humorous novels The Haunted Bookshop and Parnassus on Wheels, but a respected literary editor and critic in his own time) gave credence to de la Roche’s evident talent, and her distinctive authorial voice.

Two more promising novels followed, the critically acclaimed Possession, in 1923, and Delight, a less popularly successful Thomas Hardy-esque rural satirical romance, in 1926. In 1927, the work that was to launch Mazo de la Roche’s career into the Canadian and eventually worldwide literary stratosphere was published. Jalna was a a soap-opera-ish family saga centered on an old Ontario family, the Whiteoaks, headed by a wealthy matriarch. Something about it caught readers’ imaginations, and, when Jalna unexpectedly won the prestigious Atlantic Monthly $10,000 cash award – a small fortune in 1927 – for “most interesting international novel of the year”, it assured its author’s financial security and allowed her the freedom to write full time. At the age of forty-eight, Mazo’s creative life was about to become very much the focus of an overwhelmingly adoring public and a varied group of intensely opinionated critics.

Mazo de la Roche and Caroline Clement, 1930s

Caroline was now able to retire from wage-earning work and she took on the role of her suddenly-famous cousin’s housekeeper, editor, secretary, and collaborator in creativity. “The Play”, so precious to the two in childhood and maintained throughout the years, continued to expand in their leisure time, as the cousins ought respite from the pressures of fame in their shared imaginary world. Suffering continually from blinding headaches and trembling hands – and at least one bona fide nervous breakdown – Mazo found that the only way she could sometimes get her thoughts down on paper was to dictate them to Caroline. While Caroline always disclaimed any notion that she originated the plot lines and characterizations that Mazo was so famous for, both women were very open about Caroline’s role as a sounding board and critic.

Fifteen more “Whiteoaks of Jalna” novels were to follow that first astonishing bestseller, as well as more novels, plays, short stories and, eventually, several autobiographical memoirs, of which 1957’s Ringing the Changes is the last. Mazo de la Roche died four years later, at the age of 82. Caroline survived her cousin for some years; the two are buried side-by-side in an Anglican church cemetery in Sibbald Point, Ontario.

It is estimated that the Jalna novels have sold more than eleven million copies worldwide in the years since 1927. They have been translated into more than ninety languages, and were adapted for the stage, movies and television, with varying degrees of popular, commercial and critical success. Despite – or perhaps because of – their bestseller status, the Jalna novels were increasingly viewed with scorn by the literary world as being too “popular” and “melodramatic” in plot and execution.

Mazo de la Roche, in the decades since her death, has slipped into literary oblivion but for a few dedicated readers who staunchly read and reread the Jalna saga, and passed the books along to their children. Mostly daughters, one would assume, as de la Roche was seen as a “women’s writer”; her works were thought to appeal mostly to the bored housewife seeking sensation and emotional escape from the humdrum everyday round.

A recent (2012) documentary by Canadian film maker Maya Gallus has brought Mazo de la Roche into new focus. Both her ambitious novels and her unconventional and rather mysterious life are being examined with twenty-first century eyes. It will be interesting to see if there will be something of a “Jalna Revival”; I’m betting that we’ll be hearing much more of this not-quite-forgotten Canadian in the months and years to come.

Pertinent links regarding the recent docudrama:

NFB – The Mystery of Mazo de la Roche

Review: NFB docudrama: The Mystery of Mazo de la Roche

Quill & Quire – Interview with Maya Gallus

*****

(When reading) the autobiographies of other writers … some appear as little more than a chronicle of the important people the author has known; some appear to dwell, in pallid relish, on poverty or misunderstanding or anguish of spirit endured. They overflow with self-pity. Others have recorded only the sunny periods of their lives, and these are the pleasantest to read.

~Mazo de la Roche ~ Ringing the Changes

Mazo de la Roche and her beloved Scottie, Bunty

Ringing the Changes itself is a diverting memoir, and, if the author indeed intended to record the frequent sunny hours of her life, she by and large succeeded. Tragedy both major and minor continually followed Mazo and her extended family, and while unhappy events are described, they are not dwelt on or singled out as an excuse for pathos. I never got the feeling that the author was “wallowing”, though I occasionally shook my head in wonder at the sad fates of so many of her relatives, and, frequently, of her family’s beloved animals. They did seem, so many of them, to come to such tragic ends…

I must confess that I knew very little about de la Roche before I read this book, though I had a pre-existing vision of her as a rather reclusive, mildly eccentric sort. I had read several of the Jalna novels way back during my teenage years, but had certainly not found them worthy of any sort of “fandom”, as so many others apparently have. I did pick up a number of the books quite recently in a library sale, thinking that my mother might enjoy them, but she was rather dismissive of the series, so they currently languish somewhere in a box.

In this memoir, Mazo looks back to her childhood, and, once a bit of genealogical discussion is gotten out of the way, launches into a compelling tale of gallantry, tragedy, heartrending anecdotes and humorous vignettes. “Gallant” is a term I kept saying to myself as I read Ringing the Changes; so many of the people in Mazo’s life demonstrated this trait, in particular her beloved cousin Caroline, who was the epitome of selfless devotion in numerous ways, though she appeared to have a full and satisfying independent life as well. The Mazo-Caroline relationship is still raising eyebrows – were they lesbians? what was Mazo’s hold on Caroline? who really wrote the books? – but, seriously, it does seem like that particular relationship was one of equals. Both women apparently had romantic interludes – with men – at various times throughout their lives; that they would choose to stay single and in a “family relationship” with each other and various other family members surely is a purely personal matter and rather understandable given their backgrounds and that of their extended family.

The argument for “closet lesbianism” for Mazo at least is quite strong, or perhaps one might go so far as to speculate that “cross-gendered” might be a more apt term. From her own statements in Ringing the Changes, in childhood she wanted to be a boy, she related on completely equal terms with her male editors and literary advisors, and, perhaps most tellingly, she frankly states that she identified extremely strongly with one of her male protagonists, Finch Whiteoak, who is portrayed as artistic, emotionally and physically fragile, and highly conflicted in his romantic yearnings.

In Ringing the Changes it does seem that Mazo de la Roche was continually striking back at her many critics, the ones who denied her work any place in the “literature” canon, due to its popular success and formulaic nature. She is highly defensive of her own motivations, and this oft-quoted passage sums up her rather hurt tone well:

I could not deny the demands of readers who wanted to know more of that [the Whiteoak] family. Still less could I deny the urge within myself to write of them. Sometimes I see reviews in which the critic commends a novelist for not attempting to repeat former successes, and then goes on to say what an inferior thing his new novel is. If a novelist is prolific he is criticized for that, yet in all other creative forms — music, sculpture, painting — the artist may pour out his creations without blame. But the novelist, like the actor, must remember his audience. Without an audience, where is he? Like the actor, an audience is what he requires — first, last and all the time. But, unlike the actor, he can work when he is more than half ill and may even do his best work then. Looking back, it seems to me that the life of the novelist is the best of all and I would never choose any other.

Ringing the Changes, read as a stand-alone book without reference to Mazo de la Roche’s fictional body of work, “works” as a memoir which can be read for the pleasure of the tale itself. Mazo de la Roche was, as even her harshest critics freely admitted, a “born storyteller”, and this account of incidents in her life, as deliberately selected and edited as they may be, is a very readable thing indeed.

Read Full Post »

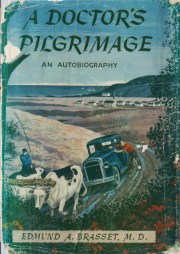

Turtle Diary by Russell Hoban ~ 1975. This edition: Picador, 1977. Softcover. ISBN: 0-330-25050-7. 191 pages.

Turtle Diary by Russell Hoban ~ 1975. This edition: Picador, 1977. Softcover. ISBN: 0-330-25050-7. 191 pages.