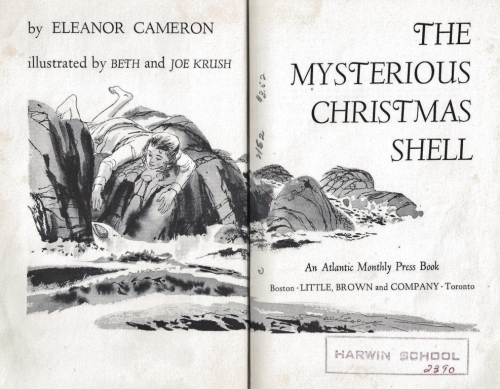

The Mysterious Christmas Shell by Eleanor Cameron ~ 1961. This edition: Little, Brown & Co., 1961. First edition. Hardcover – Library Binding. Illustrated by Beth & Joe Krush. Library of Congress #: 61-9281. 184 pages.

The Mysterious Christmas Shell by Eleanor Cameron ~ 1961. This edition: Little, Brown & Co., 1961. First edition. Hardcover – Library Binding. Illustrated by Beth & Joe Krush. Library of Congress #: 61-9281. 184 pages.

My rating: 8/10. What a nicely written book this was! It restores my faith in the joys of reading juvenilia, sadly shaken by recent forays into several more modern disappointments in the youth-oriented fiction line.

This one was a recent impulse buy from the ever-changing and happily eclectic selection at the Bibles for Missions thrift store in Prince George. I try to get there once a month or so, and I always come away with a promising mixed bag of reading material. Some goes right back into the giveaway box, but there’ve been some small treasures found there, too.

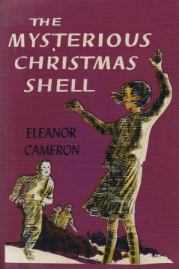

The cover illustration was what grabbed my attention, though this grubby ex-school-library book showed much evidence of many readers, and was less than appealing at first glance. (It ultimately cleaned up nicely with a triple application of soapy cloth, rubbing alcohol and a tiny dash of benzene – not in combination, I hasten to add, but in delicately selective stages.)

“Those look like Krush children,” I thought to myself, and by golly, my instinct was right. Beth and Joe Krush were a husband-and-wife team of children’s book illustrators working industriously together from the 1950s through the following decades, and their marvelously detailed pen-and-ink-and-wash drawings perfectly depicted the characters of such classics as Mary Norton’s The Borrowers and its sequels, and Elizabeth Enright’s Gone-Away Lake books, among many others.

Here’s a sample. Isn’t this appealing?

And Eleanor Cameron’s name chimed a little bell, too, though I didn’t really place it until I Googled her after I’d read the book. This is the famed Mushroom Planet creator, though those junior sci-fi fantasies were only one aspect of her widely varied output.

The Mysterious Christmas Shell is very much a plain and simple “domestic adventure” story, and it turns out that it is Cameron’s second book concerning the same brother-sister pair, Tom and Jennifer. Their earlier adventure, The Terrible Churnadryne, was published in 1959.

*****

Five days before Christmas, Jennifer and Tom arrive in the fictional town of Redwood Cove, California, on the Monterey Peninsula, to spend the holidays with their Grandmother Vining, and Aunts Vicky and Melissa. As soon as they walk into their aunts’ house, they realize something is terribly wrong. The tree hasn’t been decorated, the usual garlands are in a heap of green at the foot of the stairs, and everyone has a strained smile; occasionally they catch one or another of the adults huddled in a corner crying.

Turns out that the Vining family has had to sell its treasured piece of ancient redwood-forested seaside property, Sea Meadows, because of the year-ago death of the family partiarch, the children’s grandfather. Some investments have gone wrong, and outstanding debts needed to be paid. The purchaser, a boyhood friend of the family, was thought to want to keep the property unspoiled, to be the site of a single home, but recently troubling word has come that there will instead be major development. Hotels, a shopping centre, and a vacation community are planned; many of the ancient trees will be coming down, and No Trespassing signs will be going up barring the locals from their most pleasant seaside beaches and coves. The local townspeople are up in arms, and are angry at the Vinings for the sale; the Vinings are distraught at the prospective destruction of their well-beloved redwood forest.

An offer to re-purchase the property from the developer has been turned down, and a prospective reprieve of sorts has not come about. Grandfather Vining had intended to change his will to transfer Sea Meadows to the state as a nature reserve, but no one has any record of the will being registered, and no one knows if the envelope containing it was actually sent. If the will was indeed written, it would effectively cancel out the subsequent sale, and the property would go to the state once the buyer’s money was refunded. This seems like a way out of the dilemma, but where, oh where is the will?

As Jennifer and Tom ricochet around Redwood Cove looking for clues, we get a vivid picture of a large, loving family, each member trying to do the best for the others, though occasional misunderstandings occur.

The physical description of the California coastline, with its sea caves and pocket-handkerchief beaches, its tide pools and their glorious variety of sea life, is wonderfully well done; it is obvious that the author held the area in deep affection.

I do have an extra special reason for loving this story, having spent some weeks every year in California as a child, visiting grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins in the Fresno area, and travelling out to San Jose, Monterey, and Carmel-by-the-Sea to visit family friends and to explore the still-unspoiled seashore along the more remote stretches of coastline. I even had my own similiar near-brush with death, once being washed out into the surf by a rogue wave; my father’s heroic rescue has become a piece of family folklore, and I blame my deep but reasonably well-disguised unease about any body of water much deeper than my knees on that terrifying childhood experience. Tom, Jennifer and Aunt Melissa’s being caught in the waves of the incoming tide sent chills down my spine! I could feel the sand burns …

The familiar setting was a marvelously unexpected surprise, but putting aside nostalgia and concentrating on the writing, I must say I was impressed by the quality of the prose, and by the author’s fine story-telling ability. While this is one of those stories where nothing huge really happens, with the adventures being small ones, and the solution to the mystery very apparent to the reader from early on – the Vinings, on the other hand, struggle on for strangely long time figuring out their clues – I found I couldn’t put the book down until the satisfyingly happy (though rather improbable) ending.

A grand vintage read for adults of a certain age wishing to revisit their youth through the pages of a book, though I’m not sure how much it would appeal to our more sophisticated 21st Century children.

Despite the Christmas-time setting, this is not really a Christmas book as such, though a glass tree ornament from Innsbruck plays a major part. Oops – just gave away a clue!

It was enjoyable to read about Christmas preparations in a place far from snow, and that brought back memories, too. We only spent one Christmas in California when I was a child, as most of our travelling took place in the early spring and the fall, but I remember how surreal it was that one time to be singing carols under the palm trees, with roses still blooming and lemons on the trees in my grandmother’s garden, while back at home, in interior British Columbia, icicles reaching the ground were our parting memory as we’d pulled out of the yard for the marathon three-day drive southwards. (Somewhere I have a picture from that trip of me and my sister standing, in our matching velvet-collared coats, in front of a huge Christmas tree at Disneyland, which was ornamented by coloured glass balls as large as our heads.)

This is an author decidedly worthy of further investigation. Investigating the titles and plots of some of her non-sci-fi “realistic” children’s/teens’ novels, I strongly suspect that I read some of those when I was in grade school, as two or three of the unusual plots sound very familiar, but The Mysterious Christmas Shell was an unfamiliar, unexpected and most welcome find, for all of the reasons detailed above.

*****

Oh – one more serendipitous thing. Eleanor Cameron turns out to be Canadian! She was born in Manitoba, and though she subsequently lived most of her life in California, she is widely identified in all of the material I was able to find online as a Canadian. So – another one, completely out of the blue, for the Canadian Book Challenge!