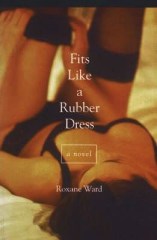

Fits Like a Rubber Dress by Roxane Ward ~ 1999. This edition: Simon & Pierre, 1999. Softcover. ISBN: 0-88924-4. 303 pages.

Fits Like a Rubber Dress by Roxane Ward ~ 1999. This edition: Simon & Pierre, 1999. Softcover. ISBN: 0-88924-4. 303 pages.

My rating: 6.5/10.

*****

Great title and teasingly provocative cover. Didn’t realize it was Canadian until I got a page or two in, though the cover blurb by Timothy Findley should have been a major clue:

“It’s a glorious book! Roxane Ward is a sorceress – she transports you into a weird world of frantic characters dancing on the edge of the millennium. Then she lets you in on the secret: it is your own world, seen through the eyes of young, super-urban artists who are never satisfied with what they have or what they find. I warrant you will not forget Indigo Blackwell, in her pursuit of a life that fits like a rubber dress …”

– Timothy Findley

I raced through this one in a single sitting, staying up much too late last night to finish it, so that is an indication of its more than decent quality. This said, Fits Like a Rubber Dress is being added to the giveaway box as soon as I record this review, as I doubt it’s a re-reader for me.

Our heroine Indigo Blackwell is 29, on the cusp of leaving her youth behind, and she is obsessed with all of the usual angst-ridden baggage this entails. Her four-year-old marriage to a freelance writer/aspiring novelist, Sam, is happy enough, though Indigo loudly complains to her husband and her best friends (bartender Tim and television presenter Nicole) that her sex life is not as exciting as it once was in the “early days” of her marriage. She obsesses about this as much as she does about the incipient wrinkles she imagines are lurking, waiting merely for the flip of a calendar page to appear. Indigo wants to have sex, lots and often; Sam just isn’t that interested, citing stress, and preoccupation with finishing his novel, and gently ignoring Indigo’s increasingly desperate attempts to maneuver him into the bedroom.

“Frustrated” describes Indigo’s general state of mind. Not only is her marriage dull and her sex life stalled out, but her career is increasingly unsatisfying. Working for a Toronto public relations company, Indigo is modestly successful in her field, but when she receives a minor promotion, her feelings of dismay surprise her. Indigo needs to spice up her life …

All of this sounds most clichéd and rather yawn-making – oh, yes, we’ve read this story before – but author Roxane Ward managed to keep me engaged enough to follow Indigo on her quest for self-fulfilment, for a life that fits her and expands with her as she “grows” and makes her look and feel oh-so-good about herself, obliquely referencing the title. This first novel is more than competently written; Ward has oodles of talent, and I am curious as to what she did after getting Indigo out of her system, though I can find no evidence of a second novel in my brief internet search this morning. Which, if so, is a shame. But I digress.

Okay, back to Indigo. Her seems-so-serene marriage is about to founder, due to Sam’s own preoccupation with sex, or, rather, the sex lives of others. Researching the Toronto gay scene for material for his novel, Sam strikes up an increasingly deep acquaintance with a male escort, Graham, though he insists that there is nothing personal going on with his fascination with that parallel world. Indigo, having decided to dump her P.R. career and go to art school to study film-making, walks in on Sam and Graham in the midst of Sam receiving some firsthand experience with male-on-male sexual practices, and though Sam insists that it is all in the nature of research and that Indigo should basically get over it already, the marriage is, from that moment of we-could-all-see-it-coming-but-Indigo discovery, doomed.

Luckily Indigo has a cozy place to escape to, as her mother has just left for Bali for an extended artists’ retreat (what wonderful lives these people lead – no one is worried about the phone bill; it’s all about self-fulfillment; but how do they pay for it?! – I wish I knew!), leaving Indigo with the keys to her house. Indigo embarks on her own sexual explorations, taking up with bad boy, drug-dealing, sadomasochistic Jon, who introduces her to the world of fetish parties and anything-goes sex. This is cool for a while, but then things go a little bit sideways, and Indigo bails out, showing more sense than I had initially expected her to have. (She is described at one point in the novel as being “malleable” – very apt, as she appears willing to go with almost anything that comes her way – so it was a happy surprise when the girl found her spine at long last.)

So at the end of the tale – and here be spoilers, so look away now if you care to – Indigo is quite happily solo, Sam is off doing whatever comes next in his life, one friend is pregnant, and another is dead. Oh, and Indigo has a new tattoo. The end.

Did that sound rather bitchy? Yeah, I guess it did. On reflection, I realize that I didn’t ever really like Indigo. She was just too self-absorbed and navel-gazy and spent so much time worrying about the really obvious things in life – yes, Indigo, we’re all going to die, and no, Indigo, drug dealing, abusive artist types are not that into empathy and understanding. Go figure.

All that aside, a good first novel in a modern-urban, slightly satirical way. Well written, good characterizations. Nicely done, Roxane Ward. I hope you’re still out there writing away, because if Fits Like a Rubber Dress is any indication, you can say it well.