Cousin Elva by Stuart Trueman ~ 1955. This edition: McClelland and Stewart, 1955. First edition. Hardcover. 224 pages.

Cousin Elva by Stuart Trueman ~ 1955. This edition: McClelland and Stewart, 1955. First edition. Hardcover. 224 pages.

My rating: This is tough. I almost was going to say un-rateable, but on second thoughts I will give it maybe a 5.5/10. It’s a first book, and the author went on to write many more. There’s nothing really wrong with it, and I did read it with mild enjoyment, but I found it very easy to put down and I had to consciously pick it up and finish it. Probably a keeper, but on the bottom shelf or exiled to the “B”-reads boxes, I’m thinking.

*****

Cousin Elva is a humourous, satirical light novel about a fictional couple, Penelope and Frank Trimble, who purchase a large house in the (also fictional?) community of Quisbis on the Bay of Fundy, and proceed to open a boarding house – “Mr. and Mrs. Trimble’s Tourist Rest Haven”. The only catch is that the house comes with a pre-existing resident, Miss Elva Thwaite, granddaughter of the original owner.

Miss Thwaite, or “Cousin” Elva as she insists on being called, is a blatantly eccentric, sixty-ish,”old maid” who refuses to be put on the shelf, taking an active interest in everyone and everything that crosses her path. She’s also keen to catch herself a man. Hi-jinks ensue as a motley assortment of visitors to Trimble’s Rest Haven fall into Cousin Elva’s clutches.

The humour is, at its best, rather understated and wry, but too often over-the-top farcical. I did enjoy the many regional and Canadian references; those did much to keep me reading when I occasionally got overloaded with the slapstick action.

A well-meaning attempt by an author new to me. The kind of book you perhaps enjoy best when scanning the meagerly stocked shelves at an isolated lakeside cabin in summer. In other words, welcome if you’re fairly desperate for amusement and it’s too far to go to town…

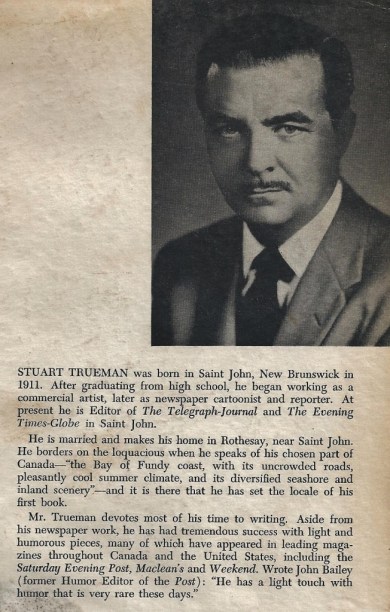

Stuart Trueman (1911-1995) was a Canadian writer from New Brunswick. He won the Steven Leacock Memorial Medal for Humour in 1969. I had never heard of him before picking up this book, but as you can see from his biography he had a long and prolific writing career. I would definitely be interested in reading some of his other work, but only if it was easily obtainable; I don’t think I’d go to a lot of effort to seek it out.

From the New Brunswick Literary Encyclopedia:

Stuart Trueman (writer, editor, historian, reporter, cartoonist, and humorist) was born in 1911 in Saint John, New Brunswick, the son of the late John MacMillan and Annie Mae (Roden) Trueman. He was the husband of Mildred Kate (Stiles) and a father to Mac and Douglas, his two sons; he was also a grandfather of four, and a great-grandfather to one. Growing up, he had two sisters and three brothers, along with a countless number of friends whom he believed shaped him into the man that he was. He passed away in his home in Saint John, New Brunswick, on 25 April 1995 after a period of failing health.

Trueman was known for being a great representative of journalism, and he garnered a lot of respect and credibility in all that he accomplished. Straight out of high school, he started out as a cartoonist and reporter at the Telegraph Journal in Saint John, where he stayed for forty-two years, later becoming a sports writer. In 1951, Trueman became the editor-in-chief at the Telegraph Journal and Evening Times Globe, a position that he would hold for the last twenty years of his working career. Upon retirement in 1971, he remained faithful to the newspapers that he had been involved with and continued to contribute to weekly columns until 1993. He took writing, journalism, and public speaking seriously, and had a keen insight into human character. He was also known for being a stickler for details, always following the journalist’s obsession with the “who,” “what,” “where,” and “how.”

Trueman was often referred to as “Mr. New Brunswick” because of his broad knowledge of the history of this province and of its scenic and cultural attractions. He wrote many books about New Brunswick, its people, and its unique history. Along with being a well-known author, Trueman was a part of New Brunswick history. On 19 May 1932, he and co-worker Jack Brayley interviewed Amelia Earhart at the Saint John Airport as she was preparing for her historic flight across the Atlantic. Another accomplishment for Trueman was when he and Brayley took a trip to Moncton, New Brunswick, where they discovered an attraction that many are familiar with today: Magnetic Hill. Trueman’s son Mac said that despite the fame and development that has built up around Magnetic Hill, it was always his father’s favourite natural phenomenon. The discovery of Magnetic Hill gave way to the tourism industry within New Brunswick, and it continues to be one of New Brunswick’s most popular attractions.

Trueman published fourteen books and wrote more than three hundred humorous articles for both Canadian and American magazines. He thought of these articles as “light pieces,” and although he never claimed they were funny, he was commonly referred to as a funny man. One of his greatest accomplishments was winning the Stephen Leacock Memorial Award for humour in 1969 for his book You’re Only as Old as You Act (1968). Other books Trueman produced include: Cousin Elva (1955); The Ordeal of John Giles: Being an Account of his Odd Adventures; Strange Deliverances, etc. as a Slave of the Maliseets (1966); An Intimate History of New Brunswick (1970); My Life as a Rose-Breasted Grosbeak (1972); The Fascinating World of New Brunswick (1973); Ghosts, Pirates and Treasure Trove: The Phantoms that Haunt New Brunswick (1975); The Wild Life I’ve Led (1976); Tall Tales and True Tales from Down East: Eerie Experiences, Heroic Exploits, Extraordinary Personalities, Ancient Legends and Folklore from New Brunswick and Elsewhere in the Maritimes (1979); The Colour of New Brunswick (1981); Don’t Let Them Smell the Lobsters Cooking: The Lighter Side of Growing Up in the Maritimes Long Ago (1982); Life’s Odd Moments (1984); and Add Ten Years to Your Life: A Canadian Humorist Looks at Florida (1989). Many of his books include light-hearted stories that have been adapted from Trueman’s popular columns in the Telegraph Journal, Weekend, and the Saturday Evening Post.

Trueman’s wife, Mildred, played an important role in his overall success as an author in New Brunswick. She supported him throughout his career, and the couple collaborated on two cookbooks: Favourite Recipes from Old New Brunswick Kitchens (1983) and Mildred Trueman’s New Brunswick Heritage Cookbook: With Age-Old Cures and Medications, Atlantic Fishermen’s Weather Portents and Superstitions (1986).

Amanda Palmer St. Thomas University

And here is the author photo and biography from the back cover of Cousin Elva: