Dodie Smith in 1921, aged 25.

Coming to the surface after blissfully submerging myself this past week in the massive memoir of one Dodie Smith: failed actress, reasonably competent department store saleswoman (and eventual mistress of the store owner), astonishingly successful playwright, bestselling novelist, Dalmatian dog lover, and all-around fascinating character.

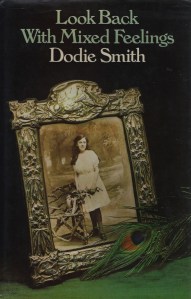

I have just read something over one thousand pages of autobiography in all, if one adds up the pages counts of her four volumes: Look Back with Love, Look Back with Mixed Feelings, Look Back with Astonishment, and Look Back with Gratitude. A fifth installment was in the works, but never published, and I find that I am sorely disappointed – I would read it with great joy.

So – Dodie Smith. Where does one start?

Perhaps I’ll merely recommend that anyone who has read and enjoyed the first volume of her memoirs, Look Back with Love, immediately go on a quest to beg, borrow or (at daunting cost – these were the Great Big Splurge of this summer’s book hunting) perhaps even steel oneself to buy the rest of the books. They are absolutely excellent.

I am personally not terribly familiar with the 1930s and 40s London and New York theatre scenes, or the Hollywood of the 1940s and early 50s, and many of the big names referenced were quite vague to me, but it didn’t matter a bit: Dodie brought these various worlds to life.

I am glad I came to these memoirs after reading a number of Dodie Smith’s novels, as my familiarity with her fictions helped me center myself in her recollections. I was intrigued and surprised to find out how many of the incidents in these fictions came from Dodie’s own life. In her case, truth is frequently much stranger than fiction; the most outrageous incidents come from life.

The bits I’d jibbed at the most in The New Moon with the Old and The Town in Bloom suddenly clicked. I’d wondered where the author was coming from with her dramatically-minded, stage-struck, teenage heroines just aching to dispense with their virginity to older (sometimes much older) gentlemen, and now I know. They are echoes of Dodie herself, though she (reluctantly) kept her “purity” until the advanced age of twenty-five, at which point she decided to take a friend’s advice and bestow it on a slightly bemused man-about town of her acquaintance. (The advice was that if one wasn’t married by twenty-five, one should feel oneself obligated to embark upon an affair, to keep one from becoming a curdled old virgin. Or something to that effect. 😉 )

All of this talk about sex makes it sound like these memoirs are rather risqué, but in truth they aren’t. Dodie is so matter-of-fact and so willing to share not just reports of her actions but abundant self-analysis of why she did what she did, looking back on her youth from the perspective of her eighties, that the potential salaciousness of these frank remembrances is disarmingly diffused.

Dodie wrote an astounding quantity of journal entries – thousands of pages and millions of words over her lifetime – and she mined out the most fascinating nuggets to embellish her memoirs, which are easy reading, words flowing smooth as silk. No doubt Dodie took endless pains to make them so, as she references a favourite tag of Sheridan’s – “Easy writing’s vile hard reading” – and states that the opposite also holds true.

She should know.

Dodie Smith, aged 14, at which point this volume of memoir begins, picking up where “Look Back with Love” ends.

Look Back with Mixed Feelings: Volume Two of an Autobiography by Dodie Smith ~ 1978. This edition: W.H. Allen, 1978. Hardcover. ISBN: 0-491-02073-2. 277 pages.

My rating: 10/10

Fair warning: These will all be rated 10/10. Grand reading experience; better than anticipated. I mean, 4 volumes of autobiography – surely one will get tired of this introspection at some point and long to put these down?

Nope.

Super-condensed recap:

The 14-year-old Dodie moves from Manchester to London with her mother and new stepfather. Stepfather proves to be unsatisfactory, emotionally abusing Dodie’s mother and squandering her small fortune. Heartbreaking turn of events as Dodie’s mother falls ill and slowly dies of breast cancer; Dodie nurses her and is present at her deathbed.

With support of her aunts and uncles, Dodie embarks upon dramatic training in London at the Academy of Dramatic Arts (later the RADA) and then on to a concerted attempt to build a career as an actress. Though she does rather better than many others, she finds a pattern emerging in which she is able to talk herself into parts, only to not be able to sustain them. Many end ignobly – Dodie refers to herself as “the most fired actress in London”.

She finds a certain amount of solace and a relief of creative yearnings in her private writing; she works on a number of plays, writes much in her journals, and dabbles in poetry.

Writing of this period in her life, 1914 to 1922, Dodie references quite frequently her later novel, The Town in Bloom, in which she includes numerous from-life experiences of herself (“Mouse” in the novel) and her friends and fellow striving actresses. The “giving up virginity” scene is apparently also drawn from personal experience, as are the other romantic and sexual goings-on of the girls in the novel. As in the novel, this volume of memoir focusses as strongly on the yearnings of a young Dodie for love and romance as much as for a theatrical career.

Gloriously funny throughout; I laughed out loud at some of the anecdotes. Wonderful descriptions of, well, everything, really. Especially of clothing. Dodie put a lot of effort into her personal appearance, dressing for effect whenever possible. Heads up, Moira, if you haven’t already dipped into this one – the descriptions are brilliantly detailed and just begging to be illustrated! (Even better than in The Town in Bloom.)

The volume ends with Dodie down on her luck, finally accepting her failure as an actress, and preparing to enter into the “civilian” workforce, as a shopgirl at the esteemed London household furnishings emporium Heal and Sons. The saga ends abruptly and rather cliff-hanger-ishly (as does Look Back with Love) – one is left poised to go on, and yearning for the next installment. And luckily, here it is, published just one year later:

Dodie Smith, circa 1932, in one of her most successful and beloved outfits to date, a grey hat and coat (with matching shoes and handbag) by “Gwen of Devon”

Look Back with Astonishment by Dodie Smith ~ 1979. This edition: W.H. Allen, 1979. Hardcover. ISBN: 0-491-02198-4. 273 pages.

My rating: 10/10

Picking up exactly where Look Back with Mixed Feelings leaves off, with Dodie stepping into Heal’s through the imposing glass entrance doors and taking on what would prove to be a respectably long stint in the retail trade – 1923 to 1931.

Dodie finds life as a working girl pulling the regular 9-to-6 shift five days a week (plus 9-to-1 on Saturdays) something of a change, but she grits her teeth and gets down to it. She has been engaged as Number Five Assistant to the section manager – a situation which rankles – Dodie must initial all of her transactions with the manager’s initials and “5” representing herself as an anonymous cog in the works – and which she soon manages to finagle herself out of, partly by intelligent grasp of her duties and promotion, and partly because (this bit is not in the memoir, but is added in by me from the accounts of others, most notably Valerie Grove in her biography Dear Dodie) Dodie has managed to secretly seduce the store owner, Ambrose Heal.

Ambrose is referred to in LBWA as “Oliver”; Dodie does a rather nice job of obscuring his identity, though when one is fully aware of the scenario many veiled references click perfectly into place. Ambrose is married, and he also already has a long-time mistress, Prudence Maufe, who is well up in the hierarchy of Heal’s. Dodie assures Ambrose/Oliver that she will be happy with “crumbs from the table”, as it were, and the two remain occasional lovers for the next 15 years or so, when Dodie makes a final break with Ambrose upon her departure for the United States on the brink of World War II. (They will remain lifelong friends and dedicated correspondents.)

Marvelous details of the workings of Heal’s; much discussion and description of the era’s domestic architecture. Dodie eventually becomes the toy buyer for Heal’s, and is sent to Leipzig Fair in Germany to view and order stock for the coming Christmas season. A side trip to Austria proves to have astonishing consequences, as Dodie there stays in a small mountain inn maintained by a harp-playing innkeeper.

Inspired by the mountain setting and the cheerful eccentricities of the innkeeper, Dodie, who has been churning out reams of dramatic manuscript and plays in her meager free time, translates her experience into what will become her astoundingly successful play Autumn Crocus, the smash hit of the 1931 London theatre season (“Shopgirl Writes Play!”) and the rest is history.

Look Back with Astonishment goes on to describe Dodie’s entry into the next phase of her life, that of a successful playwright. She was to go onto have an unheard-of six financially successful plays in a row: Autumn Crocus, Service, Touch Wood, Call It a Day, Bonnet Over the Windmill, and Dear Octopus. The quality of these varied, with Dear Octopus popularly declared to be her very best, but Dodie poured heart and soul into each and every one, and her descriptions of casting, staging, rehearsing and dealing with various actors, actresses and directors makes for fascinating reading.

Dodie’s private life has not been stagnating these years either. As well as continuing with her secret relationship with her boss, Dodie has developed another romantic partnership, one which will ultimately see her through to the end of her days.

Seven years younger than Dodie, and marvellously handsome and personable, Alec Beesley had led a life as dramatically complicated as anything Dodie could have dreamed up, and after a most difficult adolescence with a hateful stepmother had gone off to North America where he worked at a variety of jobs from section ganger on a railway in Alaska to cashiering in a Vancouver bank. Back in England, Alec has taken on the job of Advertising Manager at Heal’s, where he and Dodie meet frequently. (Often, to much eventual 3-way heart stirring, in Ambrose Heal’s office.) Com-pli-cat-ed!

Alec and Dodie eventually set up parallel households in adjoining flats; no one is quite sure what their exact relationship is, but Dodie makes mention of the happiness of both their sexual and emotional compatibility, and they do eventually marry (details in Volume 4, Look Back with Gratitude) though neither feels as though any fuss needs to be made regarding the legalization of what was long an established marriage in everything but the eyes of the public and the law.

As Look Back with Astonishment draws to a close, Alec and Dodie, along with Dodie’s beloved Dalmatian dog Pongo – yes, the inspiration for that Pongo, with much more concerning Dalmatians to follow in Volume 4 – are settling themselves into their accommodations on the ocean liner Manhattan, beginning what will prove to be a long self-imposed exile from their beloved England, due to Alec’s long and deeply held convictions as a conscientious objector and Britain’s coming entry into what will prove to be World War II. It is 1938.

I have left so much out; there is a lot in this volume! But I must move along, to the fourth and final installment:

Dodie, Alec, Folly, Buzz and Dandy (I’m not sure which of the canines is which – all these spotted dogs looking rather alike to me) in California, circa 1944

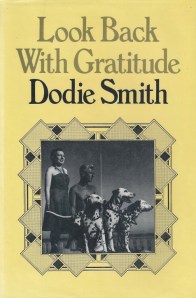

Look Back with Gratitude by Dodie Smith ~ 1985. This edition: Muller, Blond & White, 1985. Hardcover. ISBN: 0-584-11124-X. 272 pages.

My rating: 10/10

Brutally condensing here, though I could go on and on and on.

Dodie and Alec and Pongo set up house in New York and then cross the continent to California. They spend the war years engaged in various theatre and film projects; Dodie’s list of new acquaintances is a Who’s Who of the entertainment and literary world of the time. The most wonderful, for all concerned, is her finding of deeply kindred spirit and forever-more close friend Christopher Isherwood.

Pongo expires; Dodie acquires two more Dalmatians, Folly and Buzz. Folly at one point produces an astonishing 15 puppies (anything familiar here? – yes – this shows up in print down the road) of which litter Dandy is kept to make a boisterous trio.

Dodie turns her attention from playwriting and screenplays to conventional fiction, and spends three years working on what will become her first novel and what many consider her lifetime magnaum opus. That would be – drumroll please – I Capture the Castle, published in 1949 and an instant bestseller in England, once it is released there after its respectable but not stunning debut in the United States.

Much detail of crossing the continent numerous times; the agonizing internal conflict of abandoning England in wartime, the feeling of bitter homesickness and exile which never really goes away, the temporary return to England and the production of several not-very-successful plays, much agonizing on “next steps”, the long gestation and glorious birth of Castle, and much, much more.

This volume ends with Alec and Dodie returning to England for good in 1953; we leave Dodie gazing at the receding horizon of New York City through her stateroom porthole on the Queen Elizabeth.

A fifth volume was planned and apparently mostly written, but never published. I am bitterly disappointed; there is much more to tell and Dodie is by far the very best person to tell it.

I am better than half way through Valerie Grove’s 1996 biography of Dodie Smith, Dear Dodie, and though there are snippets here and there of things not included in the original memoir, it is so far merely a repeat of what I have already heard from the subject’s own lips, as it were. I am looking forward to Grove’s coverage of the years Dodie didn’t get to, being most curious as to the circumstances surrounding the writing and publication of The Hundred and One Dalmatians, as well as the her subsequent adult novels – The New Moon with the Old, The Town in Bloom, It Ends with Revelations, A Tale of Two Families, The Girl in the Candle-lit Bath – and two more children’s books – The Starlight Barking and The Midnight Kittens.

Dodie Smith died in England at the most respectable age of 94, in 1990. Her beloved Alec predeceased her by three years. Her last Dalmatian, Charley, pined after Dodie’s death, and died a mere three months later.

Dodie Smith never produced anything which could be considered high literature; her plays, though popularly successful, were slight things, mere entertainments for the masses. Yet the best of her work lives on today and continues to appeal to a succession of new readers and audiences. Not such a shabby legacy.

Dodie Smith was a truly unique character, a complex heroine of her long personal era, and a tireless documenter of the times she lived in.

Need I add, these volumes of memoir are very highly recommended?

Read Full Post »

Within This Wilderness by Feenie Ziner ~ 1978. This edition: Akadine Press, 1999. Softcover. ISBN: 1-888173-86-6. 225 pages.

Within This Wilderness by Feenie Ziner ~ 1978. This edition: Akadine Press, 1999. Softcover. ISBN: 1-888173-86-6. 225 pages.