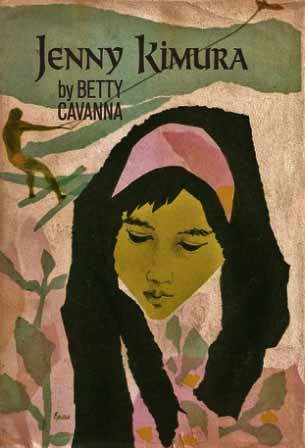

The Country Cousin by Betty Cavanna ~1967. This edition: William Morrow & Co., 1971. Hardcover. Library of Congress #: 67-21735. 222 pages.

The Country Cousin by Betty Cavanna ~1967. This edition: William Morrow & Co., 1971. Hardcover. Library of Congress #: 67-21735. 222 pages.

My rating: 5/10.

An equal balance between interestingly vintage (Paris in the sixties!) and appallingly dated (chauvinistic boyfriends!) The author did her research for this slight little teen tome, and it shows, mostly in a good way. An interesting – if feather-weight – 40-year-old read.

Bonus – great cover! Tells you everything you need to know right there up front, doesn’t it?

*****

My reading is all over the map right now. It was a toss-up this morning whether to take a stab at reviewing Stephen Fry’s sex-and-bad-language-soaked novel The Hippopotamus, or this mild little vintage teen-girl romance. But since my last review was of a very contemporary (well, 1999 – not really that contemporary, though it seems but a moment ago in some ways), sex-filled book – Fits Like a Rubber Dress by Roxane Ward – I decided to keep things all mixed up; from one I wouldn’t dare to give my dear old mum to one she’s enjoyed with gentle enthusiasm. (As did I.)

Melinda Hubbard – Mindy – has grown up on a large farm in Pennsylvania, and now, recently graduated from high school and facing all the “next step” big decisions, is at a loss with how best to proceed. Her beloved older brother Jack, her opposite in almost every way – strong, intense, smart and focussed, where Mindy is soft, mild, merely average in academics and waffling – is studying medicine and has just married his college sweetheart, Annette.

Bridesmaid Mindy takes part in the wedding in a fog, brushing off inquiries as to her future plans with vague evasions; she’s done the proper thing and has applied to several colleges, but is ashamed to disclose that her applications have all been denied because she hasn’t met the academic standards. Her mother is pushing her towards taking a secretarial course, but Mindy is less than enthusiastic about that, not being able to picture herself sitting at a typewriter all day.

A saviour appears in the person of Mindy’s older cousin Alix. Recently widowed – we find out that her young husband was killed in Vietnam – Alix has taken the insurance money and opened a clothing store in Bryn Mawr, catering to the well-heeled college girls and their mothers. On an impulse, Alix invites her droopy cousin Mindy to come and live with her for the summer, to work in the shop – called “The Country Cousin” (after a real-life dress shop, as we find out in the author’s note at the end) – and gain some experience in the retail trade while considering her next move.

Mindy is agreeable – though one couldn’t call her “enthusiastic” – it’s really not in her nature, such a strong emotion, you know! – and soon is immersed in the retail clothing trade. If there’s one thing Mindy does enjoy, it’s pretty clothes, and we learn that she is something of an accomplished seamstress herself, designing and creating her own dresses and so on; a talent which will end up leading her to her true vocation.

Mindy meets several young men, and dabbles with romance for the first time in her life. Handsome Peter, a friend of Mindy’s brother Jack, is from a wealthy family, and has a succession of girls trailing after him, as he lackadaisically dallies with them while waiting for just the right one to come along. “I’m going to marry a rich girl,” he flat-out states to Mindy one day, letting her know that while she’s okay fun for a casual date or two, she shouldn’t get her hopes up. Realistic Mindy never really thought that Peter was for her, but she did daydream a bit, so rough and ready, definitely not wealthy and far from urbane Dana, another friend of Jack’s, on his way to study Oriental Languages at the Sorbonne in the fall term, looks very much like a second best in the boyfriend department.

Dana persists in his efforts to improve Jack’s sister’s intellectual capabilities, lending Mindy books on art, and carting her off to concerts and picnics in the country. He – and Peter, and Alix as well – all seem quite concerned with Mindy’s personal appearance. She is self-admittedly on the plump side, so with all of these people in her new life dropping comments to the effect that she’d be better-looking if she slimmed down, Mindy resolves to do just that, and tries to forget her butter-and-cream farm girl tastes, and to subsist on black coffee and a slice of toast for breakfast, and salad for lunch, and so on.

The pounds miraculously melt away, and everyone oohs and ahs about the improvement in her looks, and Mindy is quite smug with herself. And this is where I had my biggest issues with this novel. The boys in her life, and her mentoring older cousin, mention to her that she’s too fat, and that she should slim down, so she unquestionably goes along with it, and does. She drops five pounds and everyone is all over her – “Good girl! Such an improvement!” Well, five pounds isn’t all that much, is it? I can’t imagine what their conception of “too plump” must have been if that made such a tremendous difference, and the fact that they were all so rude as to say such things to her rather floors me. It was obviously socially acceptable at the time to do so; Mindy takes it without a murmur. Anyway, this bit bothered me.

So, along goes Mindy, cooperating in her rather wishy-washy way with what everyone thinks she should be doing. Alix carts her along on buying trips to New York, and Mindy is introduced to the dress trade, and realizes for the first time that perhaps she might have a vocation after all, that of fashion design. She and Alix come up with a scheme to go to Paris on a selling trip, taking along clothing sample and taking orders from the community of Americans living there, who are desperate for well-made, reasonably priced clothes; Paris apparently offers only haute couture and shoddy department store dresses, nothing in the mid-range. This venture succeeds beyond their expectations, and of course they meet up with Dana, and romance predictably blossoms in the soft Parisian air.

A pleasant depiction of the time and place and people; the Paris of the “Americans abroad” is captured very well, as is the middle- and upper-class college town atmosphere of Bryn Mawr. As a “working girl”, Mindy is frequently reminded of her place in that society – at the lower end of the food chain – but she realizes that there is a dignity and self-satisfaction about doing whatever it is that you find yourself engaged in competently and cheerfully. A teeny bit preachy, with a Great Big Moral gently tromping about, elephant-in-the-room-style, but not offensively so. Betty Cavanna is so very genuinely earnest, and her heroines are so reasonably realistic, even to their modest goals and not-very-dreadful dilemmas, that it is hard to find much to object to. Middle-class girls are “people” too!

All in all, a typical bildungsroman of the era, which holds up well to a 21st Century nostalgic re-read, if you’re into dabbling with such stuff. I’m sure the junior high school girls of the time enjoyed it greatly; the old ex-library copy I have is very well read indeed.

Now, I wonder what I should read next …