The Rescuers by Margery Sharp ~ 1959. Illustrations by Garth Williams. This edition: New York Review of Books, 2011. ISBN: 978-1-59017-460-9. 149 pages.

The Rescuers by Margery Sharp ~ 1959. Illustrations by Garth Williams. This edition: New York Review of Books, 2011. ISBN: 978-1-59017-460-9. 149 pages.

My rating: 7.5/10 for the story, 10/10 for the illustrations.

This is the first story in what eventually became a series of nine about the mice of the Prisoners’ Aid Society, and in particular the aristocratic white mouse Miss Bianca, and her admirer and co-adventurer, Bernard.

Everyone knows that the mice are the prisoner’s friends – sharing his dry bread crumbs even when they are not hungry, allowing themselves to be taught all manner of foolish tricks, such as no self-respecting mouse would otherwise contemplate, in order to cheer his lonely hours; what is less well-known is how spendidly they are organized. Not a prison in any land but has its own national branch of that wonderful, world-wide system…

In the un-specified (and purely imaginative) country these particular mice live in,

…(a country) barely civilized, a country of great gloomy mountains, enormous deserts, rivers like strangled seas…

… there exists the greatest, the gloomiest, prison imaginable: The Black Castle.

It reared up, the Black Castle, from a cliff above the angriest river of all. Its dungeons were cut in the cliff itself – windowless. Even the bravest mouse, assigned to the Black Castle, trembled before its great, cruel, iron-fanged gate.

And inside the Black Castle, in one of the windowless dungeons, is a prisoner that the Prisoners’ Aid Society has taken a special interest in.

“It’s rather an unusual case,” said Madam Chairwoman blandly. “The prisoner is a poet. You will all, I know, cast your minds back to the many poets who have written favorably of our race – Her feet beneath her petticoats, like little mice stole in and out – Suckling, the Englishman – what a charming compliment! Thus do not poets deserve especially well of us?”

“If he’s a poet, why’s he in jail?” demanded a suspicious voice.

Madam Chairwoman shrugged velvet shoulders.

“Perhaps he writes free verse,” she suggested cunningly.

A stir of approval answered her. Mice are all for people being free, so they too can be freed from their eternal task of cheering prisoners – so they can stay snug at home, nibbling the family cheese, instead of sleeping out in damp straw on a diet of stale bread.

“I see you follow me,” said Madam Chairwoman. “It is a special case. Therefore we will rescue him. I should tell you that the prisoner is a Norwegian. – Don’t ask me how he got here, really no one can answer for a poet! But obviously the first thing to do is to get in touch with a compatriot, and summon him here, so that he may communicate with the prisoner in their common tongue.”

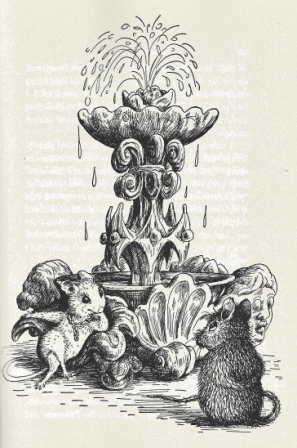

Now, getting to Norway is a bit of a challenge, but the mice have a solution. They decide to call on the famous Miss Bianca, the storied white mouse who is the pamperd pet of the Ambassador’s son. Miss Bianca lives in a Porcelain Pagoda; she feeds on cream cheese from a silver dish; she is elegant and extremely beautiful and far, far removed from common mouse-dom. She also travels by Diplomatic Bag whenever the Ambassador and his family move – abd they have just been transferred to Norway. Perfect!

A pantry mouse in the Embassy, one young Bernard, is assigned the task of contacting Miss Bianca and enlisting her aid in the cause. She is to find “the bravest mouse in Norway”, and send him back to the Prisoners’ Aid Society so he may be briefed on the rescue mission.

Bernard successfully convinces Miss Bianca to assist, and then the real action starts. By a combination of careful planning, coincidence and sheer luck, the Norwegian sea-mouse Nils, Bernard and Miss Bianca venture forth to bring solace and freedom to the Norwegian poet.

The illustrations by Garth Williams are absolutely perfect. Here is one of my favourites, of the journey to the Black Castle. Look carefully at the expressions on the horses’ faces, the fetters on the skeleton. Brrr! Danger lurks!

The illustrations by Garth Williams are absolutely perfect. Here is one of my favourites, of the journey to the Black Castle. Look carefully at the expressions on the horses’ faces, the fetters on the skeleton. Brrr! Danger lurks!

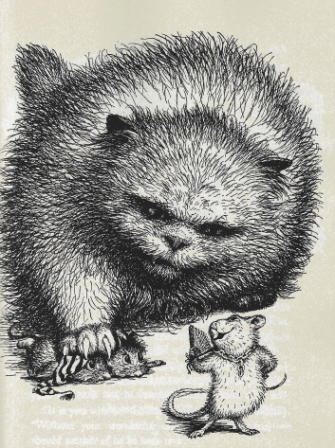

And here is Mamelouk, the Head Jailer’s wicked black half-Persian cat, whose favourite pasttime is spitting at the prisoners through the bars, and of course catching and tormenting any mouse who ventures into his dark domain.

Miss Bianca proves herself more than a match for Mamelouk, utilizing her special bravado and charm. Needless to say, the mission is successfully accomplished, though not without setbacks.

A light, rather silly (in the best possible way), rather enjoyable story.

Miss Bianca is a very “feminine” character, in the most awfully stereotyped way possible, but there are enough little asides by the author that we can see that this is not a reccomendation for behaviour to be copied but rather a portrait of a personality who uses the resources at hand (her charm, her beauty, her effect on others) to get things done.

Bernard is typical yeoman stock, earnest striving and quiet bravery in the face of adversity. He is attracted to Miss Bianca as dull and dusty moth to blazing flame, but quietly accepts that their places in the world are too far apart to ever allow him the audacity to woo her. Or possibly not…

Nils galumphs through the story in his sea boots, “Up the Norwegians!” his Viking cry. A reluctant (or, more appropriately, unwitting) hero, who has had his adventure thrust upon him, Nils typifies dauntless.

Read-Alone: I’m thinking 8 and up. Margery Sharp has written a children’s tale with completely “adult” language and references; a competent young reader will find this challenging but rewarding. Be prepared to clarify occasionally, if your reader is of an inquiring mind. (Hint: Better bone up on Lloyd’s Register of Shipping.)

Read-Aloud: I think this would be a very good read-aloud. Ages 6 and up. Reasonably fast-paced. The first few chapters set the scene and may be a bit slow going, and the dialogue will require careful reading; you’ll need to pay attention while performing this one – no easy ride for the reader! – but I think it could be a lot of fun.

Definitely worth a look. If this is a hit, there are eight more stories in the series. I have previously reviewed the second title here: Miss Bianca

Kingfishers Catch Fire by Rumer Godden ~ 1953. This edition: Reprint Society, 1955. Hardcover. 280 pages.

Kingfishers Catch Fire by Rumer Godden ~ 1953. This edition: Reprint Society, 1955. Hardcover. 280 pages.