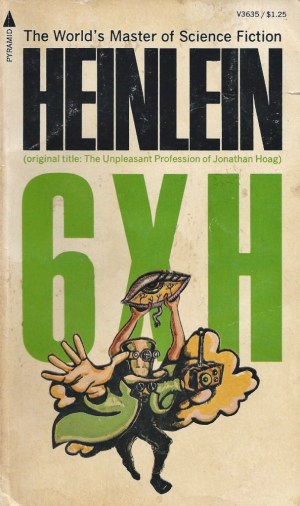

6 X H – Six Stories by Robert A. Heinlein ~ 1959. Original Title: The Unpleasant Profession of Jonathan Hoag. This edition: Pyramid Books, 1975. ISBN: 0-515-03635-0. Paperback. 219 pages.

6 X H – Six Stories by Robert A. Heinlein ~ 1959. Original Title: The Unpleasant Profession of Jonathan Hoag. This edition: Pyramid Books, 1975. ISBN: 0-515-03635-0. Paperback. 219 pages.

My rating: 5/10. More or less.

I discovered the vast, strange, swirling ocean of science fiction in high school, and have dabbled happily along the edges of that varied genre ever since. That time being in the 1970s, the prolific Robert A. Heinlein was still front and centre of the revolving sci-fi paperback rack in the school library, and his books were readily available at our town’s rather dingy little secondhand bookstore, located down a precipitous set of stairs in the cramped basement of a main street store.

This volume is a relic of that era. Definitely not built to last, the pages are yellowing and loose in the binding, the glue having long since reached its expiry date. The smell of the dusty pages takes me instantly back to those high school days. Newly employed at a part-time job waiting tables at our town’s Chinese restaurant, I had money of my own for the first time in my life, and after putting aside most of it into a savings fund targeted for buying my own car, I splurged my tips on books, books, books – a few new, but most secondhand; you could get more for your money that way, and the selection, then as now, was vastly superior.

That first car, a bright red ’72 Mustang, was purchased the summer I turned 15, for $800 cash, from a quiet young man with a highly pregnant wife (looking back over the years, I suddenly realize the significance of that situation, and my heart bleeds a bit for both of them, but at the time all I felt was sheer selfish desire, no room for empathy in my egotistical teenage heart) – and, oh! – how many hours of sore feet and cigarette smoke and ever-greasy uniforms – remember the hideous waitress garb of the time? – none of this “wear your own clothes” stuff that today’s “servers” get away with – how many early morning and late night hours at $2.65 an hour (before deductions) did this translate to?! – always doing homework frantically during a much-too-short meal break…

My father co-signed the papers for me (I was underage for a legal transaction) against my mother’s most strenuous objections, and after that most of my money went for gas, for despite not yet having a driver’s license I managed to put a lot of miles on that beautiful beast. Different times, different times…

My sweet first ride is sadly long gone, but many of the books of those halcyon teenage summers remain in my now-massive book collection, triggering little episodes of nostalgia which I savour for a moment before turning back to my present-day world. (Which happens to include this book blog, so here I go, digression over, with my review.)

This is an odd collection even for all-over-the-map Heinlein, and it’s probably been a good thirty years since I read it; I had no memory of most of the stories and it’s definitely not in the favourites pile. Sorting out the last few boxes of my old possessions from my mom’s attic, I found this and immediately put it aside, thinking my sci-fi buff teenage son might like it; he read it and passed it back to me with that current expression signifying mild disinterest – “Meh!”

“No way, it’s Heinlein, must be something good in there!” I declared, and promptly read it myself. And, sorry to say, I guess this time he was more or less right. As he usually is. Quite a lot of fun, actually, having a teen sharing some of my reading tastes. Great excuse to pick up yet more books, equipping the kid with his own library, for when he moves out, you know… For what it’s worth, he’s already on his second car. Nowhere near as cool (hot?) as his mom’s first one, though.

Okay – FOCUS.

Six short stories, more fantasy than science fiction.

- The Unpleasant Profession of Jonathan Hoag. At 120 pages, more of a novella than a short story. Originally published in the pulp magazine Unknown Worlds, in October of 1942, under one of Heinlein’s pseudonyms, John Riverside.

It starts promisingly enough:

“Is it blood, doctor?” Jonathan Hoag moistened his lips with his tongue and leaned forward in the chair, trying to see what was written on the slip of paper the medico held.

Dr. Potbury brought the slip of paper closer to his vest and looked at Hoag over his spectacles. “Any particular reason,” he asked, “why you should find blood under your fingernails?”

“No. That is to say – Well, no – there isn’t. But it is blood – isn’t it?”

“No,” Potbury said heavily. “No, it isn’t blood.”

Hoag knew that he should have felt relieved. But he was not. He knew in that moment that he had clung to the notion that the brown grime under his fingernails was dry blood rather than let himself dwell on other, less tolerable, ideas.

The fastidious Mr. Hoag has a problem. His evenings, nights and mornings are normal enough; he arrives home from work, socializes normally enough, goes to bed, sleeps and risess – but he has absolutely no memory of how he spends his days; no idea what his profession is; the only clue is the brownish-red residue under his fingernails, and a deep sense of foreboding that he is involved in something terrible.

After being turned away with no satisfactory answer by the brusque Dr. Potbury, Mr. Hoag decides to have himself followed. He contacts the firm of Randall & Craig, Confidential Investigators, who turn out to be a husband and wife team working out of their home. Edward and Cynthia (Craig) Randall are well experienced in everyday investigations; after some debate they agree to take on Mr. Hoag’s case, and the plot immediately thickens.

Up to this point the story is engaging and very nicely written; the mood is very 1940’s noir; we’ve all been there before, and we look forward with anticipation to the next logical step. And this is where Heinlein mixes things up. A straightforward “tailing” apparently is successful but goes strangely awry; Edward easily follows Jonathan Hoag to his workplace, a commercial jeweler’s workshop on the 13th floor of a city office building, and talks to Mr. Hoag’s employer. The mysterious red powder turns out to be jeweler’s rouge; Mr Hoag polishes gemstones. Case closed.

But hang on… why did Cynthia see Edward stop and talk to Jonathan, and why does Edward insist they never made contact? Why, when they both retrace Edward’s steps, do they find that there is no 13th floor in the building, and no record of a jeweler’s workshop? And why do none of Jonathan’s contacts and references seem to exist, and why doesn’t he have fingerprints?

Not content to those questions unanswered, to give Mr. Hoag the easy and plausible explanation of the jewel polishing job, and take his hefty fee, Cynthia and Edward decide to push further. And this is where things get really odd. Suddenly things are far from normal in the Randall & Craig world. Mirrors become portals into another reality; strange men with other-worldly powers enter and leave and drag Edward and Cynthia along. The threatening “Sons of the Bird” warn them to drop Mr. Hoag’s case and forget they ever heard about him, or face dire consequences.

After much hocus pocus and mumbo jumbo, Edward and Cynthia more or less get to the bottom of the strange situation, which is more than this reader ever really did. I had to go back and reread the last half of the story, and I was still confused. Something about alternative worlds improperly erased, with Mr. Hoag as a sort of unwitting Nemesis controlling rogue members of a previous world. I think.

Some great writing in this story; Heinlein struts his storyteller’s stuff here, but the plot was crazy-confusing for better than half of it, and the whole thing dragged on way too long. The main characters, aside from the mysterious Mr. Hoag, are Cynthia and Edward, and their close relationship is very well handled; their offhand manner to each other and continual wise cracking hide a deep and abiding love for each other which ultimately allows them to escape from the disaster their meddling has precipitated.

The ending of the story is as mysterious as the beginning, and I won’t really give too much away by sharing it here.

When he goes out to the vegetable patch, or to the fields, she goes along, taking with her such woman’s work as she can carry and do in her lap. If they go to town, they go together, hand in hand – always.

He wears a beard, but it is not so much a peculiarity as a necessity, for there is not a mirror in the entire house. They do have one peculiarity which would mark them as odd in any community, if anyone knew about it, but it is of such a nature that no one else would know.

When they go to bed at night, before he turns out the light, he handcuffs one of his wrists to one of hers.

Good work, front and back of this novella. Some slippage there in the middle, Mr. Heinlein!

I would be interested to hear from anyone else who has their own ideas about this tale.

- The Man Who Traveled in Elephants. Written in 1948, and published in the magazine Saturn in 1957 under the title The Elephant Circuit.

This is a rather sweet, very nostalgic, Ray Bradbury-ish tale of a retired traveling salesman and his ultimate destination. Something of an ode to the mid-century tradition of local exhibitions and fairs, and all the best things about them. I won’t say too much about this one; there’s not much to it, just a gently sentimental little fantasy. Not a masterpiece, but rather enjoyable in its own small way. There’s an old dog, too. Need I say more? It works.

- “-All You Zombies-“. Originally published in the pulp magazine Fantasy & Science Fiction, March, 1959.

Time travel and a sex change operation and some cheeky acronyms – see if you can get the connection between the “service” organizations Women’s Emergency National Corps, Hospitality & Entertainment Section, and Women’s Hospitality Order Refortifying & Encouraging Spacemen. (I know – GROAN. This is why, despite his many flaws, I like Heinlein – he makes me laugh despite my better judgement! The guy sure had a thing for acronyms – he was my introduction to TANSTAAFL, among others.)

A weird little “future tale”; pure Heinlein fantasy. Rather offensive and not as funny as the author obviously thinks it is, but it has a few points. A temporal agent on a recruiting mission with the cover profession of bartender – cute concept. For 1959. This one shows its age. And I’m surprised it wasn’t first published in Playboy. Definitely adult in theme!

- They. Published in 1941, in the pulp magazine Unknown.

A rather Kafkaesque story concerning a man who is being held in confinement of some sort (mental institution? hospital?) because of his extreme paranoia – he insists that he is surrounded by a conspiracy to deceive him as to the true state of the world, and that his is the only “reality” he can be sure of. But is it paranoia if it’s true? One of Heinlein’s experiments in defining solipsism – the philosophy that one can only be sure of one’s own mind; everything else may only be a creation of that mind.

A bit too deep for me. Well written, with a good twist in the end, but overall – “Meh.”

- Our Fair City. Published in Weird Tales, 1949.

An odd little urban fantasy. A sentient, apparently feminine whirlwind – yes – the kind of whirlwind that swirls about picking up dust and bits of rubbish – named, of all things, “Kitten” by “her” friend Pappy, an old parking lot attendant, plays a part in bringing corrupt city officials to justice. A playful farce of a story; I’ll grant points in that it’s kind of a fun concept; but my reaction was “read it quick and move on”.

“-And He Built a Crooked House-“. Astounding magazine, February, 1941.

A uncategorizable story (probably closer to sci-fi than fantasy… or vice versa – can’t decide!) about a California architect who designs and builds a three-dimensional house based on a four-dimensional tesseract. The whole concept made my head hurt; math and science geeks will no doubt fully “get” this, though. Anyway, an earthquake shifts the house fully into the fourth dimension, while being toured by the architect and his clients.

Heinlein, a quite brilliant mathematician in his own right, obviously indulged his arcane sense of humour here. Farcical and clever and probably best appreciated by like-minded sorts. I mildly chuckled, but mostly was just happy the book was finally over.

*****

So – final verdict? It was an interesting excursion into the long-ago world of Heinlein’s literary B-sides, but it can safely go back into the box. Maybe in another thirty years it will bring my grownup kid some $$$ as he flogs the excess of my book collection on the future equivalent of eBay!

If you see it cheap cheap cheap in the used book by-the-door bins, go ahead & pick it up. In my opinion, not really worth more than a dollar or two, unless you’re a dedicated Heinlein collector.

Read Full Post »

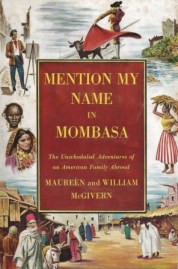

Mention My Name in Mombasa: The Unscheduled Adventures of an American Family Abroad by Maureen Daly McGivern & William McGivern ~ 1958. This edition: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1958. First Edition. Hardcover. 312 pages.

Mention My Name in Mombasa: The Unscheduled Adventures of an American Family Abroad by Maureen Daly McGivern & William McGivern ~ 1958. This edition: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1958. First Edition. Hardcover. 312 pages.