Well, hello, 2017! You’re three days old, already. Racing right along, aren’t you?

Surfacing from a very quiet and blessedly peaceful Christmas season, marred only by a viral thing which has been going the rounds locally. We thought we’d dodged it, but no such luck! – it’s hopped gleefully from family member to family member, morphing merrily into an eclectic assortment of unpleasant symptoms.

We’re all still delicately sniffling, but the worst appears to be over (touch wood!) so holding onto the thought that our immune systems will be all the stronger for it. I rather suspect 2017 will be much about finding silver linings, so this is an appropriate start, don’t you think?

Christmas brought books galore, a nice assortment of local history and horticultural tomes, with a dash of vintage fiction.

I won’t be talking about it quite yet, but I just want to mention to fellow Heyerites that I did indeed receive The Unknown Ajax, and, as you all promised me, it is utterly excellent. I read it immediately upon receipt – such a treat!

An Infamous Army is en route, too, though it appears to be hung up in the postal system. I hope to have my hands on it soon, and my expectations are high.

I did manage to start my Century of Books off quite appropriately with 1900, with a bit of what can only be deemed as literary “fluff”. About as challenging as candy floss to consume, and, expectedly, just as sustaining. But it did have a certain appeal, and it was a very quick read, and it gives me an excuse to perhaps further explore the works of this rather notorious writer.

Elinor Glyn it is.

You know:

Would you like to sin

With Elinor Glyn

On a tiger skin?

Or would you prefer

To err

With her

On some other fur?

The reference is of course to the exotic and (for their time) shockingly erotic bestsellers penned by Mrs. Glyn, beloved by the female working classes as the epitome of “escape literature”, and deeply scorned by the literary critics for all the usual reasons.

The Visits of Elizabeth was Elinor Glyn’s first literary effort, and it is a mild little concoction compared to what came after. The book had an immediate success. My personal copy was printed in 1901, the ninth impression, which is indicative of an enthusiastic reception by the book-buying masses.

The Visits of Elizabeth by Elinor Glyn ~ 1900. This edition: Duckworth & Co., 1901. Hardcover. 309 pages.

The Visits of Elizabeth by Elinor Glyn ~ 1900. This edition: Duckworth & Co., 1901. Hardcover. 309 pages.

My rating: 6/10

At some point at the close of the 19th Century – Victoria is still very much on her throne – 17-year-old Elizabeth sets off on a series of visits, accompanied by her maid Agnes, and the good advice (via unseen letters) of her mother.

It was perhaps a fortunate thing for Elizabeth that her ancestors went back to the Conquest, and that she numbered at least two Countesses and a Duchess among her relatives. Her father had died some years ago, and, her mother being an invalid, she had lived a good deal abroad. But, at about seventeen, Elizabeth began to pay visits among her kinfolk…

As we can see by the delicately engraved “portrait” so thoughtfully provided as a frontispiece, Elizabeth is a lovely young thing.

As we can see by the delicately engraved “portrait” so thoughtfully provided as a frontispiece, Elizabeth is a lovely young thing.

She cultivates a strong line in unconscious naïvety, which supplies most of the humour throughout this otherwise rather cynical, one-sided epistolary novel. (We read all of Elizabeth’s letters to her stay-at-home Mama, but nary a one from her Mama to her.)

She’s always going on about the various quirks of personality, manners, dress and appearance of the people she bumps up against, and for a while we’re not quite sure if her outspoken assessments are meant to be as cutting as they at first appear, but it soon becomes evident that Elizabeth is not harbouring any particular malice, but rather merely a child-like propensity to burble on about the first thing that crosses her mind.

This rather astonishes the worldly, mostly wealthy people she finds herself among. The more experienced and hardened of the women generally find themselves rather jealous of her fresh beauty and unmarred reputation, while the men uniformly fall at least a little bit in love with her, to absolutely no avail, because Elizabeth isn’t playing the flirtation game.

Well, not very seriously, anyway. With the possible exception of one particularly “objectionable” man, whom she has turned off with a slap early on, but who keeps popping up when least expected.

No surprises in how this frothy story ends, and, though blatantly classist and occasionally racist (the French and the Germans come in for some serious slamming, not to mention the upstart nouveau riche Jews who dare to assault the ever-more-fragile glass ceiling of the British class system) in general our heroine settles herself down enough to become quite likeable by the turning of the final page.

Her Mama would undoubtedly be pleased.

There are little hints here and there of Elinor Glyn’s keen eye for the provocative moment which she evidently developed in her future novels, lots of to-ing and fro-ing in midnight corridors, and veiled glances, and double entendres, misunderstood to great comic effect by our innocent heroine.

Elinor Glyn herself led a rather fascinating life, and it is claimed that many of her amorous plotlines came from her own broad experience, including the tiger-skin novel itself, Three Weeks, which featured an anonymous woman-of-nobility enjoying a temporary erotic dalliance with a much younger man.

Elinor moved to Hollywood in 1920 to work as a screenplay writer. Her own novel It was made into a highly successful silent movie in 1927, propelling actress Clara Bow to super-stardom as “The It Girl”.

Glyn’s novels are probably of most interest to today’s readers in the “cultural literacy” sense alone, and I rather doubt that I myself would have chosen to track down and read The Travels of Elizabeth if it weren’t for the need for an interesting 1900 book for my Century. But its promise of light entertainment and my curiosity about a writer I had only known by reference combined to bring it into my hands, and I must say I would be very willing to read another of the later books, if only to see what all the fuss was about.

A small digression here about the antique (or vintage) book as an artifact in its own right. I do love to read books in as close to the original edition as I can find them. There is something deeply satisfying in handling a book in the form in which its author would have seen it go into the world. Dog-eared pages and marginal notes and affectionate inscriptions all add to the appeal, to the feeling of connection with fellow readers of long before our time. Never mind foxing or a bit of mustiness – if the pages are intact and readable I’m all for it no matter how tattered.

This is a handsome little production in the purely physical sense, its green cloth covers enhanced by silver embellishments. The end papers at first glance look to be merely of an interesting checkerboard pattern, but on closer examination proving to be made up of 4-book stacks with spines all reading “Mudie” in different fonts. (For the famous Mudie’s Lending Library, one assumes.There is also an embossed Mudie & Co. Limited stamp on the back cover.)

A really lovely engraving of the titular character is inserted opposite the title page, protected by a glassine sheet.

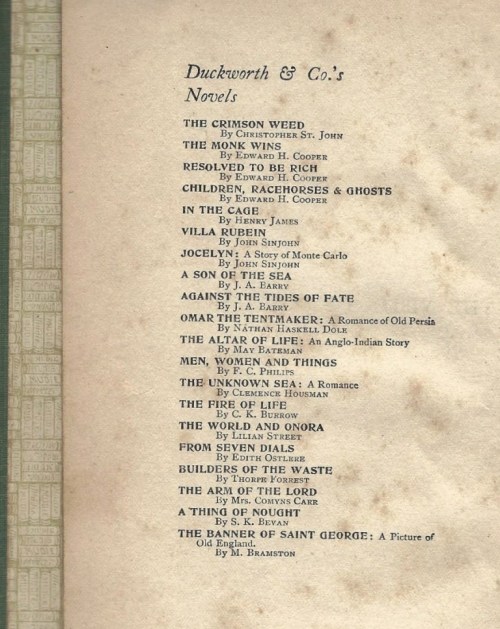

And, most intriguing of all, we find a page listing a tempting array of other Duckworth and Co.’s Novels, not a single one of which I have heard of, including In the Cage by Henry James. Is it the Henry James? Let me see…. Why, yes, it is. A novella from 1898, apparently.) But, oh! – how I wish I could get my hands on a few of these for their titles alone. Children, Racehorses & Ghosts, anyone? Or how about Omar the Tentmaker? The Crimson Weed? The Monk Wins?

Potentially delicious book discoveries wait round every corner!

Cheerio, all.

And a slightly belated but most sincere Happy New Year!

The Shuttle by Frances Hodgson Burnett

Posted in 1900s, Century of Books - 2014, Read in 2014, tagged American-British Relations, Century of Books 2014, Frances Hodgson Burnett, Nobility & Commoners, Social Commentary, The Shuttle, Vintage Fiction on January 26, 2014| 23 Comments »

My rating: 8.5/10

Coming late to the party with this book, I am. I had added it to my Century of Books must-acquire list because of numerous enthusiastic recommendations from other bloggers, and I am thrilled to be able to report that those who gave it the nod were completely correct. It’s an absolutely grand read.

I understand that the currently in-print edition published by Persephone has been edited somewhat, and I can’t help but wonder what they cut out. I’m not terribly concerned that it would have ruined the story – this is a very long book with abundant authorial wanderings just slightly off-topic here and there – but it was intriguing to read the early, as-published text in this lovely vintage edition and speculate as to where it could be gently trimmed.

And golly, I just realized that the book I’m holding in my hands (well, it’s actually sitting on top of the printer beside the computer, but it was just being held in my hands) is a genuine antique. One hundred and seven years old. That’s rather a pleasant thought. It’s travelled through the decades very well indeed, both in physical condition and in staying power of contents.

If you are one of the few of my readers who hasn’t yet tackled The Shuttle, here is a plot summary of sorts.

There were once, in the later years of the 19th century, two American millionaire’s daughters, eighteen-year-old Rosalie (Rosy) and ten-years-younger Bettina (Betty) Vanderpoel. It was just at the time of the first awareness by impoverished English gentlemen of the nobility – second, third and fourth sons, as it were – that here was a rather well-stocked hunting ground for well-dowered wives, who would be willing to exchange the country of their birth and a goodly portion of their fathers’ wealth for an English title and a stately ancestral home. In the best of these transactions, gone into with eyes wide open, both parties benefitted and a certain degree of happy felicity resulted, but occasionally the meeting of American feminine independence and English masculine traditionalist views on the necessity for a wife to submit to her husband’s superior judgement ended in disaster.

Guess which kind of marriage sweet, frail, loving and deeply innocent Rosy Vanderpoel made?

Falling for the seductive wiles of Sir Nigel Anstruthers, Rosy trots innocently off to England, but the honeymoon voyage is not even half over before she realizes that she has yoked herself to a malicious and sadistically abusive man. Sir Nigel is a rotter through and through. He despises not only his new wife, but her family and her country and her ideas and her expectations of at least a modicum of domestic happiness. His bitter disappointment at Rosy’s father’s insistence at leaving the control of her fortune in her own hands and not in her husband’s has Sir Nigel seething; he has hidden his true nature well, but now that the shores of the new world are receding he is preparing to gain control of Rosy’s share of the Vanderpoel millions for himself.

Competently reducing meek Rosy to a grey shadow of her former self, Sir Nigel succeeds in cutting her completely off from her American family, but for the occasional letter requesting more funds. Three babies are born; the first a son, who is born crippled due to his pregnant mother being physically assaulted by Sir Nigel; two little daughters die young.

Ten years pass.

Back in America, Betty Vanderpoel has never forgotten her beloved older sister, and can’t quite believe that the cessation of relations is by Rosy’s wish. (Betty had never liked Sir Nigel, and he returned the scorn she viewed him with in spades.) Taking her father into her confidence, Betty announces that she is going to go to England and see for herself how Rosy is faring. And off she goes, with her father’s blessing and his millions behind her.

What she finds is beyond her worst expectations. Rosy, aged beyond her years, lives a dreary life shut up in a decrepit mansion staffed by sullen servants, her only companion her hunchbacked ten-year-old son, Ughtred. (Aside to author re: “Ughtred”. What the heck, Frances Hodgson Burnett? That is absolutely bizarre. What were you thinking???!) Anyway, the estate is mouldering away while Sir Nigel pursues his merry way a-spending Rosy’s money on mistresses and riotous living abroad; he returns only to indulge himself in spousal abuse and to browbeat Rosy into sending another brief letter to Papa requesting more money to maintain his little grandson’s estate.

Betty, made of much sterner stuff than Rosy, swoops in like an avenging goddess, and the majority of the rest of the book consists of the rehabilitation of Rosy, Ughtred, the estate and the attached village full of grateful rurals. Sir Nigel reappears to find his despised sister-in-law very much in control of things, and their ensuing battle of wills, Rosy’s deeply good against Sir Nigel’s blackly wicked, is a gloriously entertaining thing.

Oh, and there is a further development. The next estate over belongs to another impoverished nobleman, this one the sole survivor of a long succession of bad eggs. But is Lord Mount Dunstan really as deeply black as his spendthrift, now-deceased elder brother, and the heedless ancestors before him, or is he sullen merely because he feels so darned bad about the decrepit state of his hereditary acres? Any guesses?

I will stop right here, because you can now likely guess the ending from what I’ve just said. Nope, no surprises here. But how the author gets us to the inevitable conclusion is deeply diverting. And how genuinely engaging and interesting her various characters are, from meek Rosy to divinely competent Betty to nasty Sir Nigel and his equally nasty old mother to misunderstood-but-really-deeply-noble Mount Dunstan to random American typewriter salesman G. Selden (who makes up a merry little sideplot himself, what with his precipitous entry via bicycle wreck at the very door of the Anstruther mansion) to busy millionaire Reuben Vanderpoel – what a glorious cast!

I loved this story! It’s a proper saga. Such a treat to have a black and white, good-versus-evil, you know who to root for and who to boo and hiss at sort of thing!

And it does reflect some very real historical happenings, such as the astounding trans-Atlantic traffic in (relatively) poor English noblemen and wealthy American heiresses which took place from the 1860s well into the early 1900s. Fictional Rosy Vanderpoel is represented as being one of the earlier of the transplanted rich girls, and her story is based solidly on fact, though with artistic license in her particular details.

A grand exposition on both American and British social structure of the late nineteenth century, with abundant detail and a whole lot of humour. What a good book, in an old-fashioned novel-ish sort of way. If you haven’t read it already, may I suggest that you consider adding it to your Must-Read list, in any edition you can get your hands on? As the publisher’s poster claims, it is a masterpiece.

Edited to add this note on the heroine’s wee little nephew’s name, Ughtred. At first I thought, “No way! This can’t be a real name.” But then a commenter said something about old Saxon names, and the penny dropped. Of course. A bit of internet research (what did we do before Google?!) turned up just a few references, enough to show that Frances Hodgson Burnett did indeed know her stuff. Here we are, then, references from several genealogy websites. (And I did not bookmark the references; bad researching practice, I know. Don’t tell the teens in my family, as this is a constant refrain from me when they are doing online research: “Reference your sources!”)

and

So there it is. A name with a genuine and quite fascinating history. But I still pity the poor kid in The Shuttle. Crippled from before birth by his wicked father, and then saddled with this. It’s even more eyebrow-raising than Little Lord Fauntleroy’s Cedric. Wonder what his (Ughtred’s) middle name (names) is (are)?

The publisher’s American publicity poster from 1907.

Read Full Post »