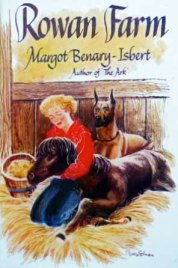

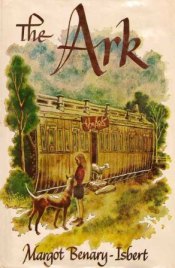

The Ark by Margot Benary-Isbert ~ 1948 (German edition: Die Arche Noah) ~ English edition, 1953. This edition: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., circa 1963. Translated from the German by Clara and Richard Winston. Hardcover. Library of Congress #: 52-13677. 246 pages.

The Ark by Margot Benary-Isbert ~ 1948 (German edition: Die Arche Noah) ~ English edition, 1953. This edition: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., circa 1963. Translated from the German by Clara and Richard Winston. Hardcover. Library of Congress #: 52-13677. 246 pages.

My rating: 10/10. This is an excellent piece of juvenile historical fiction. Actually, that designation is not really correct, as it was written as a piece of “straight fiction”, being written during the time of its setting, but to readers today it is most definitely historical, so I will classify it as that.

While not a deliberately Christmas-themed book, The Ark features two Christmases as it covers a little more than a year in the lives of its characters, and it was one I thought of when I was pondering which fictional Christmases stand out as memorable in my mind.

*****

The Lechow family – Mother, 15-year-old Matthias, 14-year-old Margret, 10-year-old Andrea, and 7-year-old Joey – are apprehensively but optimistically looking forward to their new home. Since being displaced from their village in Pomerania in the early years of the war, they have been separated – Mother and Matthias to work camps and the younger children to various farms – but they are finally together again and have been travelling through Germany seeking some place of refuge amongst the hordes of other homeless, wretched, often-starving people. They had made it to Hamburg, for a brief respite among relatives, but with the city filled with Occupation troops they were unable to get a permit to stay, and were instead assigned to accommodation in a town in Hesse. Yet another boxcar ride, and then nine more months in a refugee barracks, and their turn for a housing assignment has finally come. Number Thirteen Parsley Street – the name sounds like something from a fairy tale, and they hold their breath in anticipation of what they will find there.

And they are looking forward as well to having some sort of permanent address to share with the Red Cross, for the family’s beloved father, a doctor serving with the German army, has last been heard from a year ago with a tattered postcard sent from a Russian prison camp. Every place they’ve stopped the Lechows have registered their names, “dropping breadcrumbs in the forest” like a fairytale tribe of lost children, hoping beyond hope that Father will one day be released, now that the long war is over, and will be able to track them down from the traces they have left behind.

The owner of the Parsley Street house is appalled and offended at having to receive five penniless refugees. Elderly widow Mrs. Verduz has weathered the war reasonably well, though her nerves are “shattered” from the noise of all the bombing. Her street has miraculously stayed mostly undamaged, and though food and fuel is in terribly short supply, she fully appreciates her good fortune in having a roof over her head and all of her beloved possessions around her. She grudgingly shows the Lechows the two attic rooms she has been ordered by the Housing Authority to allot to the Lechows, and muttering in thinly veiled disgust, she raids her well-equipped cupboards for sheets to cover the mattresses she’s had to provide, and a few dented pots and pans and some chipped dishes as well – the Lechows quite literally have nothing but the clothes on their backs and a blanket each.

Once the family is settled in to their new home, things do begin to look up.

Matthias is assigned work as a bricklayer’s flunky working on reconstruction, which, though far from his true interests, astronomy and nursery gardening, at least provides a small income, and the acquaintance of a co-worker – soon to be new friend – the musical Dieter, who lives in the cellar of a bombed-out house with his raggle-taggle refugee companions, who have started an increasingly successful band called “The Cellar Rats”.

Andrea goes to public school, and is fortunate in passing an examination and receiving a scholarship to a private school run by the nuns. Here she meets butcher’s daughter Lenchen, and the two become bosom friends, with Andrea exchanging help with homework for lunchtime sandwiches provided by Lenchen’s grateful mother. Andrea is sternly forbidden to angle for anything more, but the odd morsel falls her way – a boon in these very hungry times.

Young Joey also goes to school, with less enthusiasm than his sister; he reluctantly acquires a smattering of knowledge, but his happiest acquisition is a friend of his own, a perky orphan named Hans Ulrich – last name and birth date unknown, as his only childhood memory is of being bombed, and of his mother dying when they were travelling together in a boxcar in the early years of the war, when Hans was only two or three; he was unable to tell his last name so no family was able to be tracked down; he is a waif in the truest sense, though his foster-mother (who we suspect may be getting by as a prostitute) is kind enough in her careless way.

Mother gratefully settles into the small space she can at last call her own, and immediately sets about creating a home for her brood. She smooths down Mrs. Verduz, helps her with the housework, and begins to take in sewing jobs – she is an accomplished seamstress, and finds that this skill is in high demand as people start to once more have the interest in dressing themselves well, now that the fighting is over, and life is turning to a new normal. New clothes and cloth are impossible to get, but a skilled seamstress can do much with old curtains and various patches and pieces from worn-out garments tucked away in clothes chests. Mrs. Verduz has lent a sewing machine in return for mending work, and the two women are becoming partners in the challenge of keeping everyone clean and clothed and fed. Contrary to Mrs Verduz’s fears, having a family of children in residence is not such a bad thing. Matthias chops firewood and brings home the precious small coal ration, Margret has taken over the tedious job of standing in line for hours to collect food rations, Andrea washes dishes and sweeps the stairs, while Joey brightens her life with his happy disposition.

The only one who is left in limbo in this new life is Margret. She willingly does all that is asked up her, competently handling her many menial and tiresome chores, but she is just too old, at 14, for priority to return to school, and just too young to be assigned to a job, though her mother has suggested that an apprenticeship to a professional seamstress might be a good next step. Margret is secretly appalled at the thought of spending her life bent over a sewing needle; her true life was left behind back on the Pomeranian farm which is now lost forever. There she was deeply immersed in gardening and in caring for her animals, and in rambling the countryside with her beloved twin brother Christian. A gaping hole in the family, and in Margret’s grieving heart, is carefully veiled over by everyone – Christian was shot and killed by a Russian soldier who broke into their house during the battle which ultimately displaced the family and started their years of wandering.

Christmas comes, and the family celebrates with true joy and gratitude. The Lechow children, Lenchen and Hans Ulrich and Dieter and his band decide to go Christmas carolling into the countryside, hoping for a few morsels of food or a coin or two from the relatively more prosperous farmers living around the outskirts of the town. In the course of their travels that wintry night they come to Rowan Farm, home of the widowed Mrs Almut and her elderly household. Anni Almut is a bit of a character in the neighbourhood. Endlessly energetic and outspoken, she forges ahead with whatever she sets her hand to. She has a few milk cows, raises milk sheep and ponies, and best of all to Margret’s startled recognition, keeps a breeding kennel of Great Danes. The Lechows kept Great Danes as well back in the good old days; Margret’s beloved dog Cosi was shot along with Christian, and that is another unhealed wound in her heart.

One thing leads to another, and six months later both Matthias and Margret are working and living at Rowan Farm. They have fixed up an old railcar on the farm as a dormitory, with bunk beds and a cookstove, and soon begin to fill it with the stray animals which are attracted to Margret as moths to a flame, and their town relations and friends, who are eager to come out to spend a day or two at “Noah’s Ark”, as the rail car has been christened, a refuge from the stormy seas of the outside world.

As this is a children’s book, everything continues to come together for the best, with the lost finding their way home, and old wounds healed, and the future looking positive. But the hardships and horrors of the war, though not detailed, are very much a part of the story, which ultimately celebrates the goodness that people find in the midst of the most terrible situations.

The returning soldiers are physically maimed and emotionally wounded, but they do start to heal; those who are lost are remembered with poignant sadness but not dwelled upon for the most part, as “life must go on”. The dreadful food and living conditions are dealt with creatively and are made the brunt of much humour. Our final impression is of a people and a country looking to the rising sun of a new day with optimism and hope, with a glance back to the horrors they have been involved in and a “never again” resolve.

This is a World War II book which does not reference the Holocaust and the Jewish displacement and slaughter, except by veiled allusions which most young readers will not catch. It does however in no way excuse what has happened. It rather focusses on the other innocent victims of the war, the common people, the small town shop shopkeepers, the peasants and farmers, the families and children of Germany who suffered horribly while the men were off fighting and the bombs exploded all around. People died in horrible ways, and froze and starved to death in the bitter winters even after the official truce was called. This is all in there, in the shadows behind the joy of the Lechow’s story of recovery and a happy ending.

Die Arche Noah was released to great acclaim in Germany in 1948. It caught the attention of American publishers, and was translated and released in an English edition in 1953, and was received with deep appreciation in North America. The author, beginning her writing career at the age of 59 – she was born in 1889 and had lived through the two great wars in Germany – went on to write several more children’s and young adult books, which were also translated and found ready sales overseas. Margot Benary-Isbert, herself having lost her family home and being displaced by the war, immigrated to the U.S.A. in 1952, becoming an American citizen in 1957. Her stories show her great love of both of her countries, the beloved Germany of her birth and the American haven which adopted her so graciously as it did so many other refugees from conflicts worldwide.

The Ark is often deeply sentimental and a bit “old-fashioned” in style and tone to modern ears, but the story is powerful and memorable, and strikes a strong chord with many of its readers. I was ten or eleven when I read it for the first time in my school library. I eagerly searched out the rest of Benary-Isbert’s works – our school libraries were lavishly stocked back in the 1970s – they had everything! – and when I settled into my own home and started building my book collection the Benary-Isbert books were among the first I thought I’d like to track down from my childhood favourites. Sadly they are mostly out of print, and long gone from library shelves, but were so popular in their time that they are still very readily obtainable in the online second-hand book marketplace, which is where you will have to search them out.

Read Full Post »

Akavak: An Eskimo Journey by James Houston ~ 1968. This edition: Longmans Canada Limited, 1968. Hardcover. 80 pages.

Akavak: An Eskimo Journey by James Houston ~ 1968. This edition: Longmans Canada Limited, 1968. Hardcover. 80 pages. Well depicted details of traditional Inuit skills, as well as a compelling storyline make this novel a good read-alone or read-aloud for primary and intermediate grades, and it will work well as part of a Canadian/Arctic/Inuit Life social studies/humanities unit. The novel is set pre-European-contact (or perhaps in an isolated location); while there is a slightly educational tone to a few of the author’s explanations of customs or habits, the story is very respectful of Inuit culture without over-emphasizing its “exotic” nature to readers not of the North.

Well depicted details of traditional Inuit skills, as well as a compelling storyline make this novel a good read-alone or read-aloud for primary and intermediate grades, and it will work well as part of a Canadian/Arctic/Inuit Life social studies/humanities unit. The novel is set pre-European-contact (or perhaps in an isolated location); while there is a slightly educational tone to a few of the author’s explanations of customs or habits, the story is very respectful of Inuit culture without over-emphasizing its “exotic” nature to readers not of the North. The story itself provides not much in the way of surprises; the adventuring pair overcome their frequent setbacks with predictable success. There is a very real sense of the peril that they find themselves in; Houston, though allowing the titular hero to attain his goal in the end, never guarantees a happy ending to any of the incidents he depicts, adding a dash of plausibility to a highly dramatized adventure story.

The story itself provides not much in the way of surprises; the adventuring pair overcome their frequent setbacks with predictable success. There is a very real sense of the peril that they find themselves in; Houston, though allowing the titular hero to attain his goal in the end, never guarantees a happy ending to any of the incidents he depicts, adding a dash of plausibility to a highly dramatized adventure story.