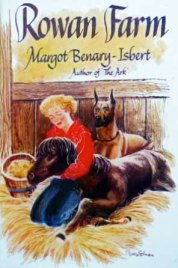

Rowan Farm by Margot Benary-Isbert ~ 1954. This edition: Peter Smith, 1990. Translated from the German by Richard and Clara Winston. Hardcover. ISBN: 0-8446-6475-8. 277 pages.

Rowan Farm by Margot Benary-Isbert ~ 1954. This edition: Peter Smith, 1990. Translated from the German by Richard and Clara Winston. Hardcover. ISBN: 0-8446-6475-8. 277 pages.

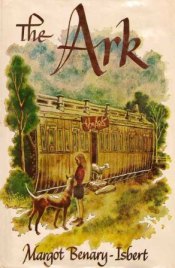

My rating: 10/10. A sequel/companion piece to The Ark.

A more mature, less “sentimental” book than the also very excellent The Ark, and a classic example of a bildungsroman – a “coming of age” story – set in 1948 and centered on 16-year-old Margret but involving many other characters as well as they react and adjust to their changing situations and the challenges of the immediate post-WW II world of defeated Germany.

*****

Rowan Farm continues the story of the Lechow family, war refugees from Pomerania who have settled into an abandoned and renovated railway carriage located on a rural farm in the Hesse region of Germany (near Frankfurt). The family’s father has made the long journey from the prison camp in Siberia where he has been interned, and the joy of the family’s reunification is still strong, though shadowed by the wartime death of one of the sons, and the emotional and physical damage Dr. Lechow is recovering from.

Other returning soldiers are finding their way home all over Germany, though for many there are literally no homes to return to. An unprecedenting readjustment of the entire population is taking place, as refugees seek a place to settle and get on with their lives, while those fortunate enough to still have their properties often grimly resent the official mandate that they must share their resources and often their homes and land with the incomers.

Bernd Almut, son of matriarch Anni Almut of Rowan Farm, has found his own way home, and having regained some of his physical strength is now trying to fit himself back into the farm life which his mother has capably managed without him for so many years. The eldest Lechow children, 17 year old Matthias and 16 year old Margret, are now integral members of the Rowan Farm hierarchy, Matthias working on the land, with Margret caring for the livestock and the sadly diminished breeding kennel of Great Danes which Rowan Farm was long famous for. Bernd and Matthias have become good friends, but that relationship founders when both become infatuated with lovely Anitra, a city girl on holiday from her studies at Franfurt University. Margret is nurturing some romantic feelings of her own towards Bernd, and he had apparently returned them until flirtatious Anitra (who can’t be all so fluffy as she looks – she is a Mathematics major) shows up. Margret deeply feels her own intellectual shortcomings; because of the war she has had to leave school some years ago, and no longer even thinks of returning to the world of studies; life has taken her a very different direction, into practical labour with her hands.

Multiple subplots abound in this novel. 11-year-old Andrea is academically gifted and is fortunate enough to be a scholarship student in the Catholic Lyceum in the nearby town; her parents are hoping that she of all of their children will be able to attend university, but Andrea has been bitten by the stage bug and has her heart set on becoming an actress. 8-year-old Joey and now-adopted “twin” brother Hans Ulrich are involved in many boyish pursuits, including raising a family of prized Angora rabbits, and running wild through the countryside every chance they get; a favourite stop is the cottage of solitary and eccentric “bee-witch” Marri, who always has a slice of bread and honey for her young visitors. Marri’s war has been a tragic one. She is the widowed mother of a lone son, a gentle and pacifistic boy; upon conscription he had willingly put on the soldier’s uniform as was his duty, but he ultimately was unable to follow orders to shoot another person, and was court-martialled and executed. Marri’s grief has brought her to the edge of madness. Fearing for her sanity, the Almuts and Lechows have tried to refocus her interest by asking her to take in a returned veteran who has himself lost his wife in a bombing raid, and who is desperately searching for his baby son, who would now be a toddler of three, if he is still alive.

There is also a young, one-armed, returned war veteran schoolmaster who falls afoul of the village mayor by involving his students in establishing a refuge for homeless soldiers; an outspoken and controversial journalist who visits the soldiers’ home and turns out to be a very unexpected individual; a American Quaker aid worker who is interested in both the Great Danes Rowan Farm raises and in the possiblilities of sponsoring the young kennel maid for emigration to the U.S.A.; a gang of black market dealers stealing local livestock; a rescued Shetland pony mare which Margret and her father nurse back to health; and two young ex-soldiers who stay for a short time until suddenly moving on, with tragic results. Musical Dieter and his band of Cellar Rats come and go, bringing a breath of the city with them as they play for the village dances and help with the haying.

Re-reading this story as an adult, I was most impressed by how delicately the author portrayed the difficulties of the returning soldiers such as Dr. Lechow. Parted from his family in the very early days of the war when he was conscripted to serve as a military doctor; finding his beloved family home in Pomerania has been lost forever; losing one of his sons – Margret’s twin brother Christian – all of these are things he takes to heart. His delicate (in his view) wife and helpless (in his mind) children have survived work camps and refugee camps and untold dangers and hardships while he himself has been incarcerated in a brutal Siberian prison camp. He finds his family at last and once he has healed enough to take an interest in their affairs, he is slightly shocked to realize that they have been functioning exceedingly well without him. His occasional attempts to regain his “beneficient patriarch” status, and his wife’s tactful handling of his delicately bruised ego and his confusion at the “new normal” he finds himself coming back to is realistically portrayed.

This story, and its predecessor The Ark, are paeans to the steadfast strength of women throughout and after the war. The men leave, usually not by choice, and either fail to return or come back terribly altered physically and emotionally. The mothers, grandmothers, wives, daughters and girlfriends who have been viewed as secondary citizens – especially in patriarchial Germany – remember that this is the land and the time of the woman’s role being defined as Kinder, Küche, Kirche – children, kitchen, church – have had to take on traditionally male tasks and for the most part have managed exceedingly well. The horrors of the war are more openly referred to in this story, including references to the death camps, and there is very much an atmosphere of both acknowledging what has happened and hoping that the future will be a more just and positive time for the survivors from all segments of German society.

All in all, a sensitive and moving story for older children (possibly 10 and up?) and adults both, inspired by the personal experiences of the author. Very highly recommended. It should follow The Ark for best effect, but can also be read alone.