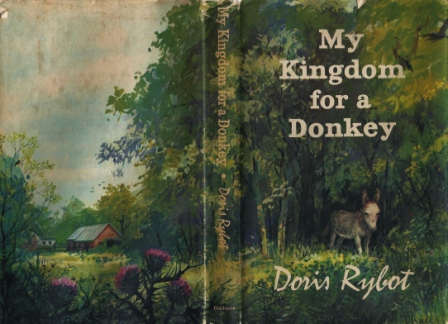

My Kingdom for a Donkey by Doris Rybot ~ 1963. This edition: Hutchinson & Co., 1963. First Edition. Hardcover. Line drawings by Douglas Hall. 128 pages.

My rating: Another unique book which is hard to rate. It’s centered on the author’s pet donkey, Dorcas, with predictable anecdotes about the creature itself, but it also ranges much more broadly into history, philosophy, animal rights and general opinionating by the author.

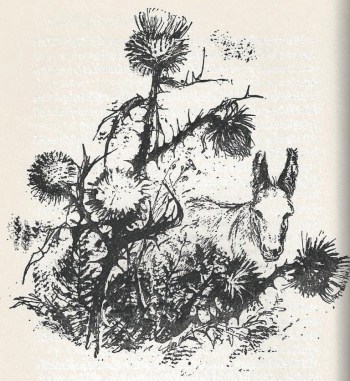

I liked it. I initially bought the book to give to a donkey-owning friend, but am finding it difficult to make up my mind to let it go just yet. And I love the illustrations. I should send it on its way back out into the world, but I strongly suspect I won’t.

Anyway – rating. I’m thinking 8/10. A slender little volume, but earnestly written, and beautifully sincere. Almost makes you yearn for a donkey of your own. (“Or not!” exclaims my reading-over-the-shoulder daughter, who has spent a number of sessions brushing out the knots in down-the-road Fanny’s woolly coat.)

*****

I’ve been carrying this one around with me for weeks, to the detriment of its rather fragile dustjacket, so I’ll try to pull off a quick review in my little window of time this evening so I can at last leave the poor thing on the shelf.

The author writes:

My own Dorcas is a plump, well-liking donkey. But even I – who can say of her as Sancho Panza said of his ass Dapple, she is the ‘delight of my eyes, my sweet companion’ – even I cannot call her beautiful. She is too like a child’s inexpert drawing, with her head absurdly big for the mouse-brown body that is at the same time neat and clumsy.

Poor grotesque beasts! Whose fault is it that they are as they are? From that day far down the increasing centuries, before the Pyramids, before Abraham, when the first wild ass was haltered and loaded. his kind have been abused, overweighted, beaten, ill-fed, chancily watered; kicks and goads have come their way more often than pats and praise. Little wonder they were reft of their real grace and swiftness to become the stunted toilers that we know, waifs of the world, clowns among horses, a byword for patience and humbleness.

This particular donkey has been acquired to keep the grass down on a small country acreage. She has not been neglected or abused, but instead was deliberately sought out and purchased from a horse dealer who kept the little jenny among a herd of ponies in the New Forest of England’s Hampshire region. Dorcas was a costly acquisition, donkeys apparently being rare and hard to come by in this particular place and time – England in the late 1950s – but the transaction was made and Dorcas soon adapted to her new home.

Dorcas’ new life was in no way harsh or unhappy; her days were filled with peaceful grazing and visits over the fence with many passers-by, occasionally pulling a small cart, being taken for short rides by her owner and visiting children, and, on one memorable occasion, embarrassing her owner mightily by refusing to participate in a horse show in the most public fashion possible, by rooting herself immovably in the show ring as the rest of the participants circled round in perfect form.

Dorcas provided her owner with years of interest and pleasure, mostly by her mere possession and the enjoyment of watching her carry on her natural inclinations and habits.

Doris Rybot tells the tale of Dorcas with the minimum of sentimentality – she sees her donkey and her own role as animal owner and caregiver through pragmatic eyes – but at the same time she speaks most movingly about the treatment of Dorcas’s tribe through the centuries, and expands this to a plea to treat all animals with respect. In between personal anecdotes featuring not only Dorcas but the other animals in her life, Doris retells a number of legends and Biblical stories in which the humble ass takes a prominent part.

An unusual and very heartfelt book, by a writer who has a deep and articulate love of all creatures from the lowliest insect to humankind itself. A hidden gem of a book, which I am quite thrilled (in a quiet way) to have come across.

I’ve done a little bit of background research on Doris Rybot, and have discovered little about her except that she did write at least one other book, It Began Before Noah, and that she also appears as Doris Almon Ponsonby, and that she was born in 1907.