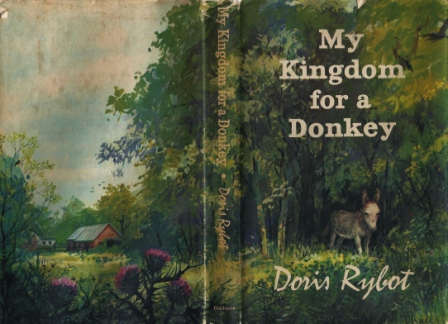

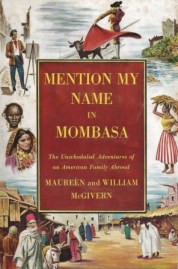

Mention My Name in Mombasa: The Unscheduled Adventures of an American Family Abroad by Maureen Daly McGivern & William McGivern ~ 1958. This edition: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1958. First Edition. Hardcover. 312 pages.

Mention My Name in Mombasa: The Unscheduled Adventures of an American Family Abroad by Maureen Daly McGivern & William McGivern ~ 1958. This edition: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1958. First Edition. Hardcover. 312 pages.

My rating: 7/10.

*****

This is a most interesting read; a travel memoir with a very 1950s’ feel – not surprising, seeing as it is a 1950s’ book! I enjoyed it.

The authors were literary figures of their time, and the travels herein described were, it seems from a few comments here and there, both to fulfill a personal desire for wanderlust and to collect material for future books, including this one.

If the name Maureen Daly rings a bell, it is most likely because of her extremely successful young adult novel, Seventeenth Summer, written when the author was herself just seventeen, and published in 1942. Some years later we find Maureen married to fellow writer William McGivern, a successful writer of crime-mystery novels (The Big Heat, Rogue Cop, war novel Soldiers of ’44, and almost 20 more) and film and television scriptwriter (Kojak, Adam-12, and Ben Casey, among others). They had their two children along, 6-year-old Megan and 2-year-old Patrick, when they left New York on New Year’s Eve to travel to Paris, the start of their extended travels.

Long, detailed and quite enthralling chapters describe the scenery, culture and especially the unique individuals the McGiverns came into contact with. The tone is a mixture of worldly-wise (but never condescending), travel guide (but merely to lay out the scene), and very 1950s’ American superiority (but innocent of bluster so therefore non-jarring – at least for the most part). The McGiverns were very eager to give credit where it was due regarding the superior aspects of their temporary homes and tourist destinations, which included Paris, and then a stay in the tiny fishing village of Torremolinos near Málaga, Spain, just on the verge of its discovery and development as a winter-tourist hotspot.

Then come several chapters on Spanish bullfighting, bullfighters and the ranches which raise and train the bulls. The tone here is journalistically non-judgemental much of the time; I never did get a grasp of whether the McGiverns were fully behind the “sport”, though from the farcical descriptions of a number of stereotypical bullfight aficionados which graces one of the chapters, I suspect they had marginally more sympathy for the bovine members of that elite yet widely populist pastime.

Next is a short visit (and hence a short chapter) in Gibraltar, where the McGiverns are rather disappointed in the elusiveness of the famous apes. On to Iceland, and a very travel-guide chapter this is, with loads of facts thrown at the reader, interspersed with short vignettes of some of the US Army families living on the vast NATO air base, and native Icelanders who opened their homes to our travellers.

Then comes the most memorable chapter of the book. During World War II, William had served as a US Army gunner in the European campaign, and his platoon had ended up entrenched on the mountainside near the tiny Belgian village of Fraipont, where the local people showed such generosity and warmth to their American allies that William had long planned to return in more peaceful times. Just over ten years later that sentimental visit took place, with the villagers overjoyed to recognize William and welcome his family. A poignant reminder that the war was not all that far in the past when this pilgrimage took place.

Back to Spain, and then a four-day voyage to the Canary Islands, a visit which seems not to have quite met the high expectations of the romance of the name. On to Morocco, where the McGiverns have several pleasant surprises regarding the locals, and then to Nigeria, on the cusp of independence as a full member of the British Commonwealth, after decades of colonial occupation.

A safari to Abadjan on the Ivory Coast and then to Fort Lamy in Chad doesn’t quite go as expected, but there are compensations in the people who the McGiverns meet as they wait for their travel visas to gain approval from the local bureaucracy. This does not happen, so back to Spain, through France, Belgium, and over to Ireland, where the Daly family is waiting to welcome their wayward relative and her family for an extended visit. Several months in Dublin follow, and then the trip is wound up, with a return to New York over a year after the original departure.

In this book there is a strong sense of how good it is to be an American at this point in history, and how welcome the traveller from the U.S.A. both feels and is made to feel; the McGiverns travel in their French-bought Citroën plastered with American flags fore and aft, and seldom seem to meet with a cold shoulder. Quite a change in the ensuing fifty years!

This is a fine book, and a literary time capsule of the post-war era, before things started to go wrong for the U.S.A., politically speaking.

I suspect it may be hard to come by (I ordered mine for a rather large sum from an online rare book dealer, for the Maureen Daly connection) but if your library happens to have a copy hidden in the stacks, or if you chance upon it in a used book store, it is well worth delving into.