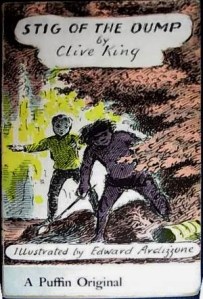

After Hamelin by Bill Richardson ~ 2000. This edition: Annick Press, 2000. Softcover. ISBN: 1-55037-628-4. 227 pages.

After Hamelin by Bill Richardson ~ 2000. This edition: Annick Press, 2000. Softcover. ISBN: 1-55037-628-4. 227 pages.

My rating: 6.5/10. Sorry, Bill. This one was a bit hit and miss with me. You got an extra point from me for old times’ sake, because I’ve been a (mostly) appreciative fan of yours since CBC Radio “Sad Goat” days.

I really liked parts of it, especially the character of Penelope, with her 101-year-old words of wisdom, and I admired the imagination of the Frank L. Baum Oz-ish dream world, but I really had to push to see this one through to the end. I kept stopping and yawning and mentally saying “Where are we? Oh, yeah, she’s in the dream world now…”

And while the bizarre (and nicely imagined – I laughed at these) realms of the ski-footed flying creatures living in the land of perpetual ice and moonlight, and the rope-skipping, directionally challenged dragons next door were quirky and funny and sweet, the dark overtones of the menace waking from its sleep struck a harsh note. And I couldn’t really get what the Piper was all about. Even if he woke, what was going to happen? I mean, how bad was it going to be? Just another magician gone wrong…

And the whole turning-eleven thing. Obviously a puberty ritual, but surely a bit young for the whole “welcome-to-womanhood” chorus of the villagers? Or maybe I’m reading too much into that. Probably a cigar is just a cigar, and it’s merely a cute plot device.

This is not a bad book, and it had some great sequences, but I didn’t immediately love it. A pleasant, light diversionary read, for mature-ish children, say 10 and up, to adult. Well-constructed “after the end of the fairytale” story. Good discussion starter, or as part of an exploration of alternative fairy tales and such.

Oh, and an extra .5 point for the talking cat. (One of my personal weaknesses. I do so love a talking cat.)

Gorgeous cover art, too!

*****

Everyone knows the story of the Pied Piper of Hamelin. How, in a town plagued with rats, there appeared a mysterious man who promised to rid the town of the creatures, and, after being promised a lavish reward, did just that, piping out a magical tune that drew them from every nook and cranny, as the piper led them far away. Coming back for his promised reward, the greedy town councillors refuse his pay, at which point the piper takes revenge by calling all of the children of the town after him, save one crippled child, who cannot keep up and so is spared. This is where the story ends. But what happens after?

After Hamelin is Bill Richardson’s fantasy about the next stage in the story. In his version, not one but two children remain behind. Penelope, who has just woken to a sudden deafness on the morning of her eleventh birthday, and Alloway, a blind harpist’s apprentice, who gets lost as the horde of children travel through a forest. Between Penelope and Alloway, Penelope’s elderly cat Scally, the village wise man Cuthbert, and his three-legged dog Ulysses, a rescue is carried out, through the medium of a trance state – Deep Dreaming – and the liberal use of magical skipping-rhymes.

Narrated by Penelope herself, who, at the age of one hundred-and-one, still looks back on her long life and unbelievable adventures with clarity and humour, the tale is told through a series of flashbacks and reminiscences.

A children’s story for all ages.

And here is an interview with the author, which puts everything into context.

Bill Richardson Interview – After Hamelin – January Magazine