Green Grows the City by Beverley Nichols ~ 1939. This edition: Jonathan Cape, Ltd., 1939. Hardcover. First edition. 285 pages.

Green Grows the City by Beverley Nichols ~ 1939. This edition: Jonathan Cape, Ltd., 1939. Hardcover. First edition. 285 pages.

My rating: 8/10. A little lush in the prose department, but ultimately I found this semi-fiction quite a likeable diversion. The chapter devoted to the author’s black, half-Siamese felines, Rose and Cavalier, won me completely over; I had been wavering a bit as the human cattiness of the narrative was sometimes rather too precious. Nichols’ affection for and description of his pets is a lovely bit of writing, appealing to anyone who shares his predilection for cats as the perfect – though endlessly demanding – home and garden companions.

The author makes no pretensions about his preferred role as planner and onlooker rather than a get-dirty, hands-on gardener. A little light watering, the plucking of a few blooms to adorn the breakfast table, maybe a mite of flower arranging to while away a slow morning, while the hired gardener does the heavy stuff under our Mr. Nichols’ interested eye…

Oh, meow! Who’s being catty now?

*****

Beverley Nichols, in his long life (1898-1883) in which he acted out the roles of journalist, author, playwright, composer, lecturer, pianist, and gay (in every sense of the word) man-about-town, alternately amused and infuriated his audience, friends and, I suspect, more than a few enemies. Possessed of a very high opinion of himself, a keenly sarcastic tongue, and a decided willingness to share his lightly censored thoughts in print, Beverley Nichols remains as readable today as he was when first published. Especially popular are his garden books, as among all the chattering nonsense and superfluous frills there are passages of very authentic admiration and insight into the appeal of that cultivated “square of ground” so universally sought after the universal tribe of gardeners, and his portraits of the plants that struck his fey fancy are small treasures of descriptive prose.

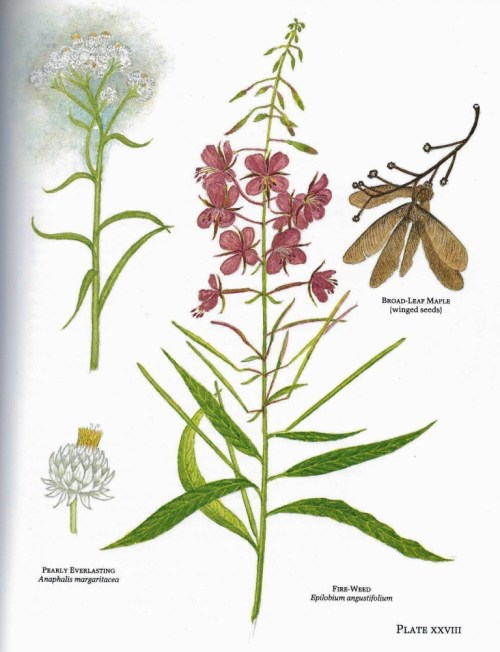

Speaking in the chapter regarding ferns, Rhapsody in Green, in Green Grows the City, of his introduction to the gold and silver ferns (Gymnogramme species) at Kew:

…(A)s I stooped to tie the (shoe)lace, I happened to glance upward. And the underside of this fern was coated with gold, pure gold, that glistened in the sunlight.

Perhaps it may sound silly to say that it was the loveliest thing that has ever come my way since I have seem life through the eyes of a gardener… I knelt down before it. The closer I came, the more lovely did the fern appear. There were no half-measures about the gold-dust with which it was so richly coated. It wasn’t just a yellow powder. It bore no sort of resemblance to the ochre make-up with which the lily is adorned. Nor was the gold dusted merely here and there – it covered every curve and crevice of the frond.

The tiny shoots that were springing up from the base were, if possible, even brighter. Since their leaves had not yet opened, and there was no green about them, they looked like delicate golden ornaments, daintily disposed about the parent plant.

And by the side of it was another excitement. A silver fern! As thickly coated with the metal of the moon as the other had been coated with the metal of the sun. If I had not realized the futility of comparisons at moments such as this, I would have dared to suggest that the silver fern was even more beautiful than the golden. For it seemed actually luminous with this magic dust. And again, there were no half-measures. It was silver. Not just white or grey, not in the least like, say, a centaurea. It was silver, hall-marked, pure and glistening from the inexhaustible mint of Nature.

What gardener could resist such a teasing description? Now in my botanical garden and specialty nursery visits I shall be forever watching for gold and silver ferns…

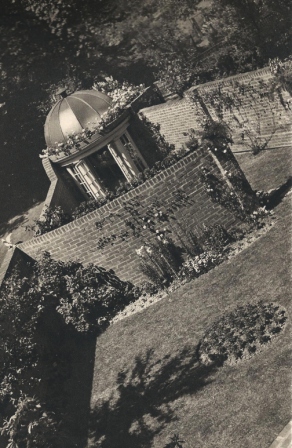

Green Grows the Garden is the fictionalized account of the creation of a very real garden. In 1936, after parting from his beloved country cottage and garden in the village of Glatton, Nichols tried the inner city life, living in a small, gardenless house in the Westminster district of London. Homesick for a bit of green, he tried without success to find a more suitable situation.

I had a hunger for green. I was lonely for the sound of trees by night. I longed to feel the turf beneath my feet, instead of the eternal pavement. Even if it were only a narrow strip of sooty grass, it would be resilient and alive, and would give me some of its own life.

Finally a small semi-detached house is found, in a close in the suburb of Heathstead. There is a garden, of sorts, a triangular-shaped bit of ground which challenges the would-be garden-designer with its peculiar idiosyncracies.

The challenge is accepted, and the transformation begins. Struggles with the site abound, not least of which is the continual protestation of every one of Nichols’ projects by the overbearing “Mrs. Heckmondwyke” of No. 1. The feud between No. 5 and No. 1 drives much of the drama of this microcosmic enterprise, though in the end something of an uneasy truce is attained.

The book is dedicated “To My Friends Next Door”, probably to nip in the bud any idea that any of them were the actual prototype of the overwhelming Mrs. H, and Beverley Nichols quite freely admits, in an evasive forward, that perhaps some of his characters owe more to fiction than to real life. The garden was a real garden, though; as were the cats and the extraordinary, imperturbable, Jeeves-like manservant Gaskin.

As the story draws to a close, the shadow of World War II is looming, and in the last chapter there is sober reference made to the outside world. Watching newsreel footage, Nichols comments:

…Line after line of youths, in brown shirts, black shirts, red shirts, any sort of shirt…marching, always marching. Backwards and forwards, to the North, to the South, to the East and West. Marching with bigger and better guns, to louder and fiercer music. Marching with clenched fists or with outstretched arms, animated by the insane conviction that the fist that is clenched was made for the sole purpose of striking the arm that is outstretched. Marching, always marching, blind to the beauty that is around and above, deaf to all music save the snarl of the drum, marching to a destination that no man knows but all men dread.

And I suspect no one will be found to argue with the often quoted final words of this little book:

…(T)hat if all men were gardeners, the world at last would be at peace.