Adventures of a Botanist’s Wife by Eleanor Bor ~ 1952. This edition: Hurst & Blackett Ltd, 1952. First edition. Inscribed by the author. Hardcover. 204 pages.

My rating: 5.5/10. Not a poor book, exactly, but not what I had hoped for, hence the low rating.

*****

A rare disappointment, this book. It had all the hallmarks of a find: rich red and gold vintage hardcover binding, gorgeous maps on front and rear end papers, photographs and line drawings by the author throughout, and an extremely promising first paragraph:

When I married, in 1931, a member of the Indian Forest Service I brought with me as a dowry two table-cloths and a bull terrier. Apart from these possessions I was a portionless bride. As his own contribution, the bridegroom brought with him a large number of books, a torn pink cotton curtain and two spaniels. Also a trouser press used for pressing botanical specimens. And some camp equipment.

How could one resist?

I had hoped for a fairly detailed account of the author’s travels with her husband through the Himalayan foothills, with lots of descriptions of the flora of the region. “Botanist’s Wife”, right? While Eleanor was obviously aware of the natural beauties of the region, she seldom describes the flora in the kind of detail I was hoping for – “a meadow of primula and gentians” is about as much as she ever says, except for a quite detailed description of a Sapria species, a type of carrion-scented flower, which was once used to decorate her bedroom by her native servants, in the mistaken belief that she and her husband, famed Irish-born botanist Norman Loftus Bor, would find it delightful – Norman had raved over a prime specimen earlier in the trip, but the foetid odour of the bloom was not at all pleasant in close quarters!

This “autobiography” does not go into much detail of the sort that makes such accounts so potentially vivid and interesting. It is something of an arm’s length travelogue, with Eleanor often commenting a bit distastefully on the hygiene (or lack thereof) of the natives of the area she happens to be passing through. To be fair, she also comments on their favorable aspects, but it is a very much “we” and “them” account.

Where she unbends the most, and where we see glimpses of her true passion, is when she talks about her beloved pet dogs – a bull terrier and several spaniels – which travelled with her, occasionally on horseback, and required an inordinate amount of special arrangement to feed and care for in a region known for its high incidence of rabies, as well as various toxic plants, predatory animals, and various nasty insects and internal parasites. Having no children, it would appear that Eleanor’s maternal affection was lavished on her pets.

This short memoir’s greatest value is that it is something of an intriguing – albeit limited – picture of the wilderness areas of northern India and southern Tibet in the time between the wars, and into the World War II years, when Norman left the forest service and was engaged in some sort of secret war work which we are never enlightened on.

I found that I had a difficult time fully engaging with the narrative. The writing is quite stilted, and throughout there are numerous very promising beginnings of anecdotes which are left hanging with no resolution or conclusion, resulting in my frequently paging back to see if I’d missed something. I never had – it just wasn’t there.

I suspect the reality of Eleanor’s life was much more interesting and varied than she was able to communicate in this book. She appears to have an excellent relationship with her husband, and numerous long-enduring friends throughout the region of her Indian travels and, indeed, throughout the world. There is a picture of the author standing next to Jon Godden (novelist Rumer Godden’s sister) and two of the “seven kings of Rupa” which is never referred to in the text, though the seven kings themselves are discussed. Was Eleanor a friend of Godden’s, or is this merely a “tourist snapshot”?

Eleanor very wanted to be a published author; she relates that she was continually writing, but hesitated to describe herself as a writer to acquaintances because she had not had anything published.

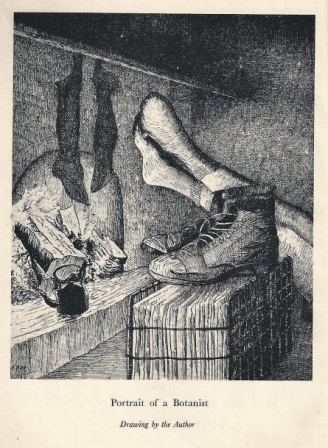

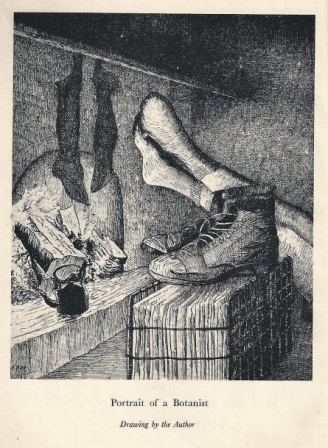

She was also a striving amateur artist; her drawings, six of which are reproduced, are capable but not particularly “good” – they look like the work of a hard-working, conscientious student – much care is taken with detail and cross-hatching, but something is a little off in perspective; they look somehow a bit lifeless. The lovely end paper maps were drawn and illustrated by Ley Kenyon; Eleanor’s painstakingly stiff drawings suffer by the comparison.

The best and to me the most appealing of Eleanor’s efforts is this illustration used in the book’s frontispiece; it made me smile and soften somewhat in my criticism toward’s her authorial failings. She tried hard and did the best she could. And as this book shows, she did succeed in her quest for publication.

Would I recommend this book?

No, I don’t think I would, unless the reader is specifically interested in the ethnic groups and fast-changing lifestyles of the people of the area during the 1930s and 1940s. The author’s perspective might be a good addition to more detailed observations.

As an autobiography, it is not one of the better memoirs I have read, though I must repeat that it is not a “bad” book; it’s just that I had hoped for so much more. I will likely keep it for its curiousity value, to slip in beside E.H. Wilson’s Naturalist in Western China as an addendum of sorts to his vastly superior work written earlier in the century.

Read Full Post »

ossypants by Tina Fey ~ 2011. This edition: Little, Brown & Co., 2012. Softcover. ISBN: 978-0-316-05687-8. 275 pages.

ossypants by Tina Fey ~ 2011. This edition: Little, Brown & Co., 2012. Softcover. ISBN: 978-0-316-05687-8. 275 pages.