The Lonely Life by Bette Davis ~ 1962. This edition: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1962. Hardcover. 254 pages.

The Lonely Life by Bette Davis ~ 1962. This edition: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1962. Hardcover. 254 pages.

My rating: 7.5/10.

*****

I’m not a particularly dedicated fan of Bette Davis, though I’ve liked what I’ve seen of her acting – films I can remember watching are Dark Victory, Now, Voyager, Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?, Death on the Nile, and of course, most memorably, that glorious 1950s classic, All About Eve. Probably a few others over the years. But I do like a good autobiography, no matter who it’s about, and this one passed the browse test recently and found its way home.

I’d wavered a bit on it, because of the price (let’s just say “not cheap”) but the bookseller kindly gave my a nice discount – without my asking, because I very seldom dicker, figuring most people in the used book business aren’t exactly getting rich. I already had a generous collection assembled on the front counter, and this particular chap believes in encouraging his repeat customers. (The Final Chapter, downtown on George Street, the block between 4th and 5th Avenue, if you’re ever in Prince George, B.C. Cheerful, chatty owner – a self-confessed “non-reader” <gasp!> – his store has a quite decent selection, affordably priced for the most part. I’ve found some prizes there.)

Back to the bio.

*****

Bette Davis comes across in this tell-all much as she does on the screen – confident, outspoken and decidedly unapologetic. She fixes her eye on the goal, and powers ahead until she gets here, quite happily stepping on as many toes as need be.

The quality of writing is quite good, if a bit choppy in style – lots of short sentences. There often seems to be an assumption that the reader will have prior knowledge of whatever’s being discussed. Fair enough, coming from such a celebrity; this memoir was published at a time when most people reading it would have been fans, with intimate knowledge of the career of this prominent movie star.

Bette Davis was born Ruth Elizabeth Davis in 1908, famously during a thunderstorm, as she relates in The Lonely Life:

I happened between a clap of thunder and a streak of lightning. It almost hit the house and destroyed a tree out front. As a child I fancied that the Finger of God was directing the attention of the world to me … I always felt special – part of a wonderful secret. I was always going to be somebody. I didn’t know exactly what at first … but when my dream became clear, I followed it.

Bette, her younger sister Bobby, and their mother Ruth – “Ruthie” – were deserted by their father and husband when Bette was seven years old. Her mother refused to wallow in self-pity, but set herself to make a successful and prosperous life for herself and her daughters. Ruthie took on a wide variety of jobs, sending the girls to good boarding schools, and always arranging to spend vacation times together in interesting locations.

Bette received an unorthodox but adequate education; she was a great reader, and took singing, piano and dance lessons, apparently excelling at all of these pursuits. At some point she decided that her Great Big Goal was a theatrical career, and several seasons of New England theatre made up Bette’s dramatic apprenticeship.

As we all know, Bette eventually made the jump from dusty New York theatres to California sound stages. Roundly criticized as being homely in appearance and with zero sex appeal, there was paradoxically a certain something about Bette that came across as mesmerizing when she took on a dramatic role, and of course, there were those beautiful eyes.

Bette was never meek or humble. From a very early age she was tremendously focussed and not afraid to set her sights high, though she often fell afoul of fellow actors and her employers for her outspoken ways. She wasn’t afraid to take on unpopular characters, or to look less than glamorous if the role called for it – another characteristic which shocked many in “the business” was her insistence on realism over “pretty”. And though she full well knew what people were saying about her, she brazenly professed not to care.

If you aim high, the pygmies will jump on your back and tug at your skirts.The people who call you a driving female will come along for the ride. If they weigh you down, you will fight them off. It is then that you are called a bitch.

I do not regret one professional enemy I have made. Any actor who doesn’t dare to make an enemy should get out of the business. I worked for my career and I’ll protect it as I would my children – every inch of the way. I do not regret the dust I kicked up.

Speaking of those children, it is very obvious from this book that Bette’s dedication to her family matched her ambition. Frankly and with bitter regret, Bette reports that her first husband convinced her to have an abortion, fearing that a baby would damage her career. Years later, with husband number three, Bette did at last have a child. Barbara Davis Sherry – “B.D.” – was born in 1947, when Bette was 39. Under doctor’s orders to avoid further pregnancies, Bette and her fourth husband later adopted two more children, Michael and Margot. Margot was later found to have been brain-damaged at birth, and after being diagnosed as severely mentally handicapped, was then institutionalized, though she continued to spend much time with her family, and appears prominently in Bette Davis’s family publicity photos.

Bette’s personal life was predictably tumultuous; she was married four times, divorced from three of those husbands, and widowed tragically when her “true love”, her second husband, died suddenly of a blood clot in his brain after collapsing while walking down the street.

The Lonely Life was written in 1961, the year after Bette’s divorce from her fourth and final husband, actor Gary Merrill, her co-star and screen husband in the iconic All About Eve.

The Lonely Life, Bette says, refers to her resolution to live without a man in her life. She’s had rotten luck with husbands; better to go it alone.

After 1962 Bette had a number of career ups and downs and come-backs; she never really retired, never rested on her considerable laurels.

Several other memoirs followed The Lonely Life. Mother Goddam (1974) and This ‘n’ That (1987), continue the tale. Bette Davis died in 1989 from breast cancer, at the age of 81.

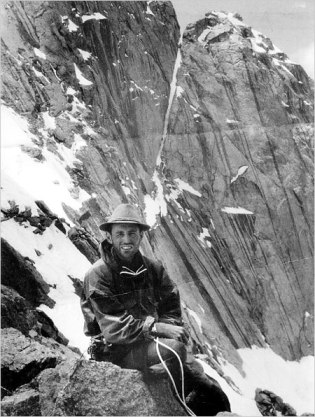

Here she is on the back cover of The Lonely Life, aged 54.

I wondered how much of The Lonely Life was actually written by Bette herself; it did have an authentic-sounding ring to it. The dedication gives the answer to this question:

I attribute the enormous research, the persistence of putting together the pieces of this very “crossed”-word puzzle which comprises my life, to Sandford Dody.

Without him this book could never have been! His understanding of my reluctance to face the past was his most valuable contribution. We were collaborators in every sense of the world.

-Bette Davis

March 8, 1962

Sandford Dody was an aspiring actor-turned-writer who ghost-wrote a number of Hollywood memoirs. His own story seems worthy of a follow-up, and my attention was caught by his 2009 obituary in the Washington Post. Dody’s version of his own life, Giving Up the Ghost (1980), is now on my wish list of future Hollywood memoirs to read.

The Lonely Life was a fast-paced and engaging, once I found my way into the choppy rhythm of the writing style. I particularly enjoyed the well-depicted childhood and young adulthood reminiscences. My interest faded a bit in the later parts, when Bette Davis talks about her film career and the encounters with studio owners, directors, and fellow stars – lots of name-dropping, and assumptions that we know what she’s going on about. Much of the time it made sense – the names were mostly very recognizable – but occasionally I felt out of the loop.

While Bette is gracious about most of the people in her life – loyalty to her chosen friends is one of her positive traits – it is obvious that there was also a substantial baggage of animosity and bitterness in some of her working and personal relationships.

I don’t necessarily like Bette Davis any more after reading this personal saga, but I did feel like I understood her, and appreciated what she had to say, and why she said it. She was frequently too strident in her self-justification for me to feel that I could really relate to the egoism of the “star” aspect of her personality, but I did feel that she came across as worthy of admiration and respect for her many accomplishments.

The perfectionist little girl with the lofty goals did achieve her ambitious destiny. She stood up for her ideals of artistic integrity her entire career. She was literate, thoughtful and highly intelligent and articulate, and she was a darned hard worker.

I put down this book with the strong inclination to seek out and watch some more of Bette Davis’s films – the ones she spoke favourably of, among the vast array of B-movies she also appeared in – so you may take this as a pleased-with-the-read recommendation.