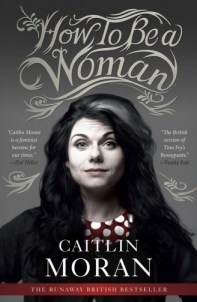

How to Be a Woman by Caitlin Moran ~ 2011. This edition: Ebury Press, 2011. Softcover. ISBN: 978-0-06-212429-6. 305 pages.

How to Be a Woman by Caitlin Moran ~ 2011. This edition: Ebury Press, 2011. Softcover. ISBN: 978-0-06-212429-6. 305 pages.

My rating: This one was unrateable.

What can I say? It’s all been said. Multiple times.

Outspoken, thought-provoking, vulgar, romantic, profane, profound, controversial, brave, rude … and very, very funny. This is not a book I would give my mother! But I would leave it where my teenage daughter could find it.

I actually did just that, and she (the teenage daughter) dipped into it, and basically said “Ew. Too much information. And swearing. She’s a bit scary, Mom.” So that didn’t take. Which is just fine. We’ve already had all of the conversations that Caitlin missed with her mother. A lot of this one reads like a cautionary tale, a what-not-do-do manual, at least until Caitlin gets herself all grown up and out in the big world. Though even then her decisions aren’t exactly stellar one hundred percent of the time.

This is a big, bold, brassy memoir of British newspaper columnist and generally funny lady Caitlin Moran’s teenage years right up until the present. She has zero barriers; she discusses everything there is to discuss about being born with on the double X-chromosome side of the human sexual spectrum. This is Caitlin’s take on what it means to be a woman. While frequently prescriptive, it’s best taken with a good dash of salt. As one reviewer quipped, this one should perhaps have been titled How to be Caitlin Moran, because it certainly doesn’t apply – or appeal – universally. Many are – and will be – sceptical, if not downright appalled, at Moran’s Technicolor rantings.

Menstruation, masturbation, obesity, body hair, pregnancy, childbirth – full coverage of the biological range. Then there are drugs and alcohol and the over-the-top excesses these can lead too. Bad relationships. Good relationships. Marriage. Children. Abortion. Right along with the ethics of employing a cleaner.

And this is what seems to be getting all the attention in the reviews I’ve been reading. Capital-F Feminism. What it looks like today, and what Caitlin Moran thinks it should look like. In a nutshell, good old Golden Rule stuff. Do as you would be done by. Treat each other well.

I’ve been thinking about how to present this review for a few days now, ever since finishing the book, and since reading fellow blogger Claire’s take over on Captive Reader – How to Be a Woman . What I’ve decided is to not really say all that much about this one. The internet is crowded to overflowing with reviews; this one has received capital-H Hype, and some people are taking it really, really seriously.

Here’s the Goodreads – How to Be a Woman page. 2500 reviews. Go wild!

I’m not taking this one terribly seriously. I found it amusing, and I agreed with Caitlin Moran on her various opinions a good majority of the time. I particularly liked her chapters on marriage and motherhood, and the abortion chapter was something very unusual in its sincerity and refreshing lack of sensationalism. I don’t think I could be so detached and unemotional as Moran was, if it were me facing the same scenario, and my decision would likely have been the exact opposite, but her forthright acceptance of what she did felt genuine.

But I’m not about to bow down to her as our newest Feminist leader, our Womanly Great White Hope, as some enthusiastic fans seem to be. She’s not really breaking any new ground here, just repeating what’s already been said with a lavish dash of shazzam.

Moran is a very funny writer. I literally laughed out loud – a rarity for me when reading – more than once – most notably during the bra and breastfeeding discussions – spot on! Loved it. I’ll likely purchase the book one day, but I’m in no rush. If I never read it again, no big deal. I’d never heard of the woman until a few weeks ago, and I strongly suspect I’ll not hear too much from her in future, but I’ve at least placed her in my personal “cultural literacy” file and can now nod knowingly if her name comes up.

And that’s good enough for me.

As a parting gift, here are some quotes I lifted from How to Be a Woman, courtesy of Goodreads. If anything here resonates, you’ll probably like this book.

*****

If you want to know what’s in motherhood for you, as a woman, then – in truth – it’s nothing you couldn’t get from, say, reading the 100 greatest books in human history; learning a foreign language well enough to argue in it; climbing hills; loving recklessly; sitting quietly, alone, in the dawn; drinking whisky with revolutionaries; learning to do close-hand magic; swimming in a river in winter; growing foxgloves, peas and roses; calling your mum; singing while you walk; being polite; and always, always helping strangers. No one has ever claimed for a moment that childless men have missed out on a vital aspect of their existence, and were the poorer, and crippled by it.

*****

I cannot understand anti-abortion arguments that centre on the sanctity of life. As a species we’ve fairly comprehensively demonstrated that we don’t believe in the sanctity of life. The shrugging acceptance of war, famine, epidemic, pain and life-long poverty shows us that, whatever we tell ourselves, we’ve made only the most feeble of efforts to really treat human life as sacred.

*****

Overeating is the addiction of choice of carers, and that’s why it’s come to be regarded as the lowest-ranking of all the addictions. It’s a way of fucking yourself up while still remaining fully functional, because you have to. Fat people aren’t indulging in the “luxury” of their addiction making them useless, chaotic, or a burden. Instead, they are slowly self-destructing in a way that doesn’t inconvenience anyone. And that’s why it’s so often a woman’s addiction of choice. All the quietly eating mums. All the KitKats in office drawers. All the unhappy moments, late at night, caught only in the fridge light.