The Twelfth Mile by E.G. Perrault ~ 1972. This edition: Doubleday, 1972. Hardcover. 256 pages.

The Twelfth Mile by E.G. Perrault ~ 1972. This edition: Doubleday, 1972. Hardcover. 256 pages.

Look what showed up in the just-past summer’s book pile.

Well, I have to admit I hadn’t exactly forgotten about it, as it was definitely a memorable read, albeit in the “so compellingly baddish you can’t look away” category.

Seems like Vancouver writer E.G. Perrault threw everything he had at this one. A number of great ideas for disaster scenarios are stacked up high, with the result that the sheer improbability of it all leads to a certain sort of morbid humour through sheer overexposure to multiple horrible things happening.

Here’s the premise.

A Canadian tugboat captain, experiencing marital woes, decides to avoid fighting with his wife by taking on a contract to haul an American oil drilling rig working just inside the Canadian twelve mile limit into safer waters to avoid an impending hurricane. Little do we know that Mother Nature (and Mother Russia) are preparing some nasty surprises for Captain Westholme and his crew.

From the back dust jacket of my first edition copy:

Christy Westholme only took the assignment to get away from his wife to think things over. It was an absolutely routine job. Take Haida Noble out of Vancouver a few miles to the big off-shore drilling rig and tow it back into port. Nothing to it, compared with some of the other towing jobs he and Haida Noble had done all over the Pacific .

Then the hurricane struck, then the tidal wave. Somehow Haida Noble survived; battered but still afloat, butting its way through mountainous seas toward the oil rig. But the rig had disappeared – in its place was a liferaft containing three Americans, one of them dead. And nearby was a strange crippled ship in imminent danger of being swept onto the rocky shore,

In the nick of time Westholme got a line aboard the strange ship and began to tow it into the nearest port. A routine salvage tow. But then he discovered that this was a Russian ship whose captain had orders not to be captured at any cost – even if the cost involved defying the Canadian Navy and Air Force, and a U.S. battleship, and taking the world to the brink of war.

Did you catch all that? It understates things.

Let me sum up our disasters:

- #1 – industrial sabotage of a British-American drill rig by the Russians (fifty workers dead!)

- #2 – hurricane

- #3 – massive tidal wave wiping out communities from California to Alaska (hundreds, maybe thousands of civilians dead!)

- #4 – hostile takeover of our hero’s tugboat by Russian spy ship (more dead people!)

- #5 – eventual destruction of spy ship including self-immolation of quite likeable Russian captain and his dedicated ship’s doctor, the luscious Dr. Larissa Lebedovitch

- #6 – international crisis triggered by Russian presence in Canadian waters bringing World War III ever closer

I think those are the “high” points.

What a depressing story. Death and destruction galore. Luckily the characters are so flat that we really can’t believe in them in any meaningful way, so when they fall by the wayside it’s really not that emotionally involving.

At least Captain Westholme and his wife get back together at the end, swearing to be nicer to each other in future. With so many people dead all around them and dozens of coastal communities in ruins, isn’t it nice that our hero and his newly adoring wife are bound for domestic bliss? Ha.

Rating this wanna-be Hammond Innes-style action-disaster novel is tough. I did read it through to the end, albeit with frequent strong urges to chuck it across the room in its stupider moments. Oh, and it was sexist, too. Though I let that pass because of the era-expectedness of the he-man commentary regarding the few, mostly offstage female characters – those whiny wives back home and the buxom female Russian sailors.

My husband tried to read this book and bailed out partway through, saying that even the unintended humour of unlikely disaster after unlikely disaster wasn’t worth the energy needed to slog through the novel’s head-hurting blend of stodgy writing and dramatic hyperbole.

Obviously my family is not the target audience for this novel, though it appears that it appealed to enough readers to cause it to go into multiple editions and several international translations.

I’ll have to give The Twelfth Mile a point for its local flavour, as it were. British Columbia coastal landmarks were well referenced throughout, adding a certain degree of interest, though post-fictional-tsunami a bunch of them were basically wiped off the map. A couple of points also for the sheer bravado of E.G. Perrault for putting forward such an over-the-top collection of overlapping dramatic episodes.

My rating: 3/10

A bit more on the author, because I feel bad about slamming this ambitious work so hard, when the writer was so obviously well-meaning.

A bit more on the author, because I feel bad about slamming this ambitious work so hard, when the writer was so obviously well-meaning.

He sounds like he was a really nice guy, and it’s probably unfair to judge him so harshly on the strength of this one novel, which means I’ll likely be keeping an eye out for his other titles as I go about my travels.

E.G. (Ernest George) Perrault was born in Penticton, B.C. and attended the University of British Columbia, graduating in 1948. According to an old UBC Alumni magazine, Perrault was one of the first students to attend one of Earle Birney’s creative writing classes.

Perrault had some success as a newspaper reporter, short story and screenplay writer. He also wrote several non-fiction books about B.C. industry and personalities. Three action/disaster novels show up bearing his name: The Kingdom Carver (1968, lumber barons in turn of the century BC : “He set out to conquer a fierce frontier… She, to tame a strong man’s angry heart”), The Twelfth Mile (1972), and Spoil! (1976, what looks like an oil derrick disaster).

Perrault had some success as a newspaper reporter, short story and screenplay writer. He also wrote several non-fiction books about B.C. industry and personalities. Three action/disaster novels show up bearing his name: The Kingdom Carver (1968, lumber barons in turn of the century BC : “He set out to conquer a fierce frontier… She, to tame a strong man’s angry heart”), The Twelfth Mile (1972), and Spoil! (1976, what looks like an oil derrick disaster).

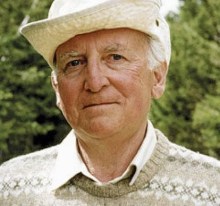

Here is E.G. Perrault’s rather poignant obituary, lovingly written by his daughter Michelle at her father’s death in 2010.

I was interested to note that Perrault did indeed have firsthand knowledge of life at sea, serving on a submarine during World War II. And yes, the strongest sections of The Twelfth Mile were those involving the mechanics of operating a tugboat, and the storm sequences.

His story began Feb. 9, 1922, the oldest of four children. His father, Ernest Perrault, succumbed to tuberculosis in 1935, leaving his wife Flossie with nothing but a small pension and a strong determination to make her children the best they could be.

His story began Feb. 9, 1922, the oldest of four children. His father, Ernest Perrault, succumbed to tuberculosis in 1935, leaving his wife Flossie with nothing but a small pension and a strong determination to make her children the best they could be.

Ernie always advised and abided by the saying “follow your bliss.” For him, this meant writing. His first short story was published in the Vancouver Sun before he was 12, when he won a children’s writing contest.

This achievement sparked a career that spanned more than 70 years, leaving his family and fans a legacy of books, plays, documentaries, short stories, radio plays, musicals and poetry that will be treasured forever. His most recent book, Tong: The Story of Tong Louie, Vancouver’s Quiet Titan, was published in 2002 and won the BC Book Prizes Roderick Haig-Brown Regional Prize. Ernie continued to write, and recently had been working on a collection of short stories.

At 18, Ernie joined the Air Force and was stationed in Yarmouth, N.S., where, as a member of 160 Squadron, he was a navigator assigned to submarine patrol off the Atlantic coast.

Ernie used his veteran’s grant to go to the University of British Columbia, where he became president of the Radio Society and wrote for the campus newsletter. He earned a double degree in English and sociology, graduating in 1948. Together with his brother Ray, Ernie received the Great Trekker Award in 1987, bestowed upon UBC alumni who have distinguished themselves in their field.

Ernie found a way to connect with everyone he met. He could carry on equally fascinating conversations with academics, business leaders, toddlers or teenagers. While he was a man of the written word, above all, Ernie was a good listener. He drew people out, helping them to appreciate and share their own unique stories.

As a city boy, Ernie had little exposure to the outdoors until a local charity gave him the opportunity to go to camp when he was 13. This experience changed his life and instilled in him a deep appreciation for nature and the wonders of the outdoors. He camped, fished, hiked and hunted. He loved sharing these experiences, especially with his four children – Lisa, Larry, Michelle and Steve – and six grandchildren, who, along with countless others, attribute catching their first fish to Ernie’s patient guidance.

Like one of his awesome campfire stories, Ernie has left us wanting more.

Michelle Perrault is Ernie’s daughter.

The Bridge of San Luis Rey by Thornton Wilder ~ 1927. This edition: Grosset & Dunlap, 1928 (later printing). Hardcover. 235 pages.

The Bridge of San Luis Rey by Thornton Wilder ~ 1927. This edition: Grosset & Dunlap, 1928 (later printing). Hardcover. 235 pages.