The Flower-Patch Among the Hills by Flora Klickmann ~ 1916. This edition: The Religious Tract Society, London, 1926. Hardcover. 316 pages.

The Flower-Patch Among the Hills by Flora Klickmann ~ 1916. This edition: The Religious Tract Society, London, 1926. Hardcover. 316 pages.

So, fellow gardener-readers, who is familiar with Flora Klickmann?

I certainly wasn’t, before I inadvertently acquired one of her many cheerful books (Weeding the Flower-Patch, I believe it was) on a visit to The Bookman in Chilliwack, B.C., and read it and was intrigued and then went on to purposefully hunt down several more.

Flora Klickmann, 1867-1958, had a background in music, but health issues in her early twenties forced her to step away from the piano. Once recovered, she started writing well-received articles on musical subjects, and in 1904 became editor of a missionary magazine, followed some years later by an appointment to the editorship of the Religious Tract Society’s exceedingly popular Girl’s Own Paper, which she successfully oversaw from 1908 until 1931.

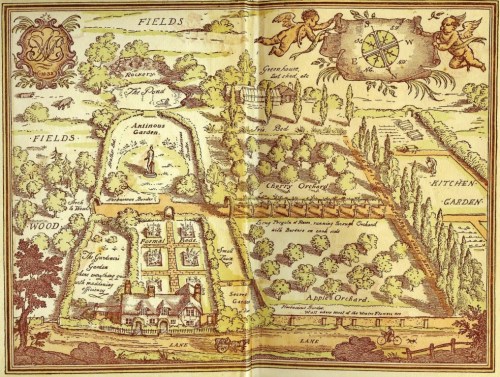

A nervous breakdown in 1912 due to overwork saw Flora convalescing in a country cottage. She found this change of venue to be so refreshing that, upon her marriage in 1913, she and her husband purchased the first of what would be a succession of rural retreats. Rosemary Cottage, home of the first “flower-patch” was “perched on the hills overlooking the Wye Valley, with views of the Welsh hills, Tintern Abbey, the river, and a distant glimpse of the Bristol Channel.”

Flora Klickmann’s branching out into full-on authorship was somewhat inadvertent, and she details it here, in the first pages of The Flower-Patch Among the Hills:

I

Just to Explain

I. Who Everybody is

Virginia and her sister Ursula are my most intimate friends. Virginia—really quite a harmless girl—imagines she has a scientific bias. Ursula—domesticated to the backbone—led a strenuous life in the pursuit of experimental psychology, till she switched off to wash hospital saucepans.

It will be so obvious that I scarcely need add: What little common sense the trio possesses is centred in ME.

Abigail is my housemaid; her title to fame is the fact that she is the only servant I have ever been able to induce to remain more than a fortnight at one stretch in the country. The others, including those who are orphans, always have a parent who suddenly breaks its leg—after they have been about ten days away—and wires for them to come home at once.

The cook has discovered a number of cousins in the Naval Division at the Crystal Palace (detachments of which pass my London house hourly, while many units partake of my cake and lemonade), and, of course, you can’t neglect your relatives in war time.

“You never know whether that’ll be the last time you’ll see them,” she says, waving a tearful tea-towel at all and sundry who march past. Naturally, she doesn’t care to be away from town for many days at a time.

The parlourmaid was interested in a member of the L.C.C. Fire Brigade, when he enlisted, and incidentally married someone else—unfortunately the very week she was away with me. This has given her a marked distaste for the simple pleasures of rural life.

Abigail is unengaged. “What I ask is: What better off are you if you are?” she inquires of space. “Take my sister, now, with eight children, and——” But as I am not taking anyone with eight children just now, the sister’s biography is neither here nor there.

Abigail is a willing, kindhearted girl. Also she has a mania for trying to arrange every single household ornament in pairs. She would be invaluable to anyone outfitting a Noah’s Ark.

As for the other people who walk through these pages, they do not appertain exclusively to one district. I have had two cottages, one beyond Godalming, in Surrey, the other high up among the hills that border the river Wye. Some of the country folk live in the one village, some in the other; but the scenery, the little wild things, and the garden are all related to the cottage that overlooks Tintern Abbey.

II. Why the Cottage is

I took a cottage in the country on a day when I had got to the fag-end of the very last straw, and felt I could not endure for another minute the screech of the trains, the honking of motors, the clanging of bells, the clatter of milk-carts, the grind-and-screel of electric cars, the ever-ringing telephone, the rattle and roar of the general traffic, the all-pervading odour of petrol, and the many other horrors that make both day and night hideous in our great city, and reduce the workers to nervous wreckage.

The cottage has been so arranged that not one solitary thing within its walls shall bear any relation to the city left far behind; and nothing is allowed to remind the occupants of the business rush, the social scramble, and the electric-light-type of existence that have become integral parts of modern life in towns.

Here, to keep my idle hands from mischief, I made me a Flower-patch.

III. Why this Book is

I was viciously prodding up bindweed out of the cottage garden, with the steel kitchen poker, when the telegraph boy opened the gate.

Unhinging my back, and inducing it into the upright with painful care, I read a message from my office to the effect that there was some hitch in regard to the American copyright of a certain article I had passed for press before leaving; this would necessitate it being thrown out of the magazine that month. Would I wire back what should go in its place, as the machines were at a standstill?

Under ordinary circumstances I should merely have waved a hand, and instantly a suitable substitute would have been on the machines with scarcely a perceptible pause—that is, if I had been in London. But such is the witchery of the Flower-patch, that no sooner do I get inside the gate than I forget every mortal thing connected with my office. And try how I would, I couldn’t recall what possible articles I had already in hand that would make exactly six pages and a quarter—the length of the one held over.

And because I could think of nothing else on the spur of the moment, I threw down the poker (it was red-rust, alas, when I chanced upon it a week later) and went indoors and wrote about the cottage and the hills.

When it was published in the magazine, readers very kindly wrote by the bagful begging for a continuation. It has been continuing—with perennial requests for more—for some time now. This only shows how generously tolerant of editors are the readers of periodical literature.

Virginia merely sniffs, “What won’t people buy!”

I don’t think she need have put it so baldly as that.

If by some miraculous chance there should be any profits from the sale of this book, I intend to devote them to the purchase of a cow (or hen, if it doesn’t run to a cow), to aid the national larder. I shall call it “the Memorial Cow,” in memory of those who have been good enough to assist in its purchase.

Should any reader wish to have the cow (or hen) named specially after him—or her—self this could doubtless be arranged. Particulars on application to the publisher.

Here’s a snippet from the body proper of this book, regarding our author’s observations on country bouquets as seen at the typical small village railway station:

There are women with empty baskets returning from market, and women seeing off friends, each carrying a huge “bookey” of flowers, built up in the approved style, from the back: first a big background rhubarb leaf, or something equally green and spacious, then some striped variegated grass – gardeners’ garters, we call it; also some southernwood – better known as Old Man’s Beard; tall flowers like foxgloves, phlox, Japanese anemones, early dahlias and sunflowers follow; the shorter stems of pinks, calceolarias, sweet williams and roses are the next in succession; finishing off with some gorgeous pansies and a very fat cabbage rose with a short stem (that persists in tumbling out), a piece of sweetbriar, and a few silver and gold everlasting flowers down low in the front. If you have a geranium in your window, etiquette demands that you add the best spray – as a special offering – to the bunch, telling your friend all about the way you got that geranium cutting , and the trouble you had to rear it.

The Flower-Patch Among the Hills is very much a wartime book, and as such is of interest on a number of different levels, in that it matter-of-factly details English country life in this unprecedented time of turmoil and change, as the Great War sets the gears grinding for what will be a major shift in the long traditions of rural England. A number of the incidents detailed concern the efforts of stay-at-homes to help with the war effort, and there is a quite delightful sequence involving the purchase of vast quantities of onion seed for sowing in amongst the garden’s flowers.

The correct term to describe this book is “charming”, and I say that with sincere appreciation. There is enough gently acerbic bite in Flora’s style to keep things from being too sugary, and as period pieces these collections of anecdote and observation are quite fascinating.

You definitely don’t have to be a gardener to appreciate them, as there are perhaps even more human interest passages than those going on about wildflowers and cottage borders and such, but if you are a plant person you will find some gleaming gold nuggets of plant observation here.

And don’t let the Religious Tract Society connection put you off, for the books aren’t anything as “preachy” as that might lead one to believe. Secularites will find little to rub them wrong, though there are occasional (okay, rather frequent) references to church-going and to the author’s personal faith. The intent throughout is merely to interest and amuse, not to convert.

My rating: 7.5/10.

Almost a “curiousity” book. Though very close to being a “hidden gem”, I hesitate to designate it as such for fear fellow readers might sight-unseen invest in one of the sometimes rather pricey copies available through antiquarian book dealers, and then not find it to their liking. Before running out on my recommendation to purchase a hard copy, perhaps it might be best to dip into the online version at Project Gutenberg. I believe there are a number of Flora Klickmann’s other titles available to read for free on that invaluable site.

A short biography of Flora Klickmann can be found here.

And a Wikipedia biography and bibliography here.

Read Full Post »

Beauty by Robin McKinley ~ 1978. This edition: Harper Collins, 1978. Hardcover. ISBN: 978-0-06-024149-0. 247 pages.

Beauty by Robin McKinley ~ 1978. This edition: Harper Collins, 1978. Hardcover. ISBN: 978-0-06-024149-0. 247 pages.