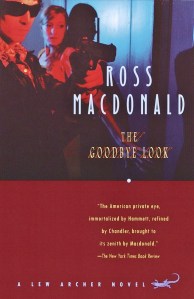

The Goodbye Look by Ross Macdonald ~ 1969. This edition: Vintage Crime/Black Lizard, 2000. Softcover. 243 pages.

The sins of the mothers and fathers are frequently visited upon their children in Ross Macdonald’s masterfully written, shades-of-gray novels concerning the cases of Southern Californian private investigator, Lew Archer. The Goodbye Look is no exception.

The sins of the mothers and fathers are frequently visited upon their children in Ross Macdonald’s masterfully written, shades-of-gray novels concerning the cases of Southern Californian private investigator, Lew Archer. The Goodbye Look is no exception.

In this case, a burglarized safe and a missing golden box containing a son’s wartime letters to his mother leads Archer on a death-plagued pursuit from “California Spanish” mansions to barbed wire fences at the Tijuana border, and back again.

Set in the Los Angeles hills, featuring vivid details and descriptions of the landscape and architecture of a particular place and time, The Goodbye Look feels appropriate reading during this past week of wildfire, destruction and displacement in Macdonald’s beloved corner of the Golden State.

That’s all I’m going to give you of the plot, because what I really want to say about Ross Macdonald is how much of a writer-of-place he is, and how much sheer good writing he packs into these novels. Genre fiction for sure, of the species mystery-noir, but of a decidedly superior sort.

The Goodbye Look is fifteenth in a series of eighteen Lew Archer novels which were published from 1949 to 1976. If you’re not already familiar with Ross Macdonald, pseudonym of American-Canadian Kenneth Millar, I suggest exploring his work. Many of his books are still in print, or are widely available second hand. E-book versions are out there, if that is your chosen format.

My rating: 10/10. Caveat: I re-read Macdonald’s books every few years, so come to them with a certain set of expectations, which are always satisfactorily met. Thinking back to my first introduction to his work, in the late 1970s, as a bookish teenager discovering a well-read paperback copy of The Doomsters on the bookshelf of a family friend while visiting in Los Gatos, California, my recollection is of a doorway opening up into the world of yet another author to explore. Oh, to be ever on the threshold of such discoveries! Such an enduring source of pleasure.

I was enormously pleased to discover, from Brian Busby’s December 2015 post on Kenneth Millar/Ross Macdonald on The Dusty Bookcase, that Kenneth Millar was born in Los Gatos. A full circle moment, as I have a nostalgically good remembrance of that community, and of all of the areas of California I was lucky enough to experience during my childhood and teen years, traveling frequently from our home near Williams Lake, British Columbia (by car, three days each way) to visit my mother’s family and an eclectic array of family friends.

I suspect that one of the personal appeals of Ross Macdonald’s body of work is the evocative experience of recalling those golden days through his writing. Though even if I’d never set foot in California in my life, I’d still rate him as high. Good stuff.

I will leave you with this excerpt from Jon Carrol’s June 1,1972 interview with Kenneth Millar in Esquire magazine. (WordPress is being fussy with linking this morning, but if you Google “Esquire June 1 1972” the whole magazine should pop up in page-by-page format. Be forewarned – you may find yourself reading much more than the Millar article. And possibly mourning the state that physical magazines have come to in these everything-online days.)

“The novel of sensibility is one of the roots of the detective story, in which an intelligent, sensitive figure travels through life—travels through Europe, for instance, as in Sterne’s A Sentimental Journey—and comments on what he sees. And I think Baudelaire had a lot to do with creating the kind of disenchanted but intensely aware person that the detective at his best represents. I think Baudelaire’s vision of Paris as Inferno has followed through in the detective story. You have London as Inferno in Sherlock Holmes, for instance. As T.S. Eliot pointed out, The Waste Land drew in part on Conan Doyle’s London.”

Macdonald’s Inferno is Southern California, the restless background of his books, a movable graveyard where everybody is from someplace else. “Southern California,” said Millar reflectively, lifting his heels a foot from the ground, knees locked, and staring down his legs at the brown half-moons of his shoe tips, “is a recently born world center. It has become a world center, in the sense that London and Paris are world centers, just in the last twenty-five years, since the war, on the basis of new technology. It’s become the center of an originative style. It differs from the other centers in that the others have been there for a long time and have more or less established a life-style and a civility which keep things pretty much under control. And they have established a relationship with the natural world, centuries old, which hasn’t changed much.

“Here in California, what you’ve got is an instant megalopolis superimposed on a background which could almost be described as raw nature. What we’ve got is the twentieth century right up against the primitive. We’re in Santa Barbara, which I consider to be one of the most cultivated cities in the world, but if you go inland ten miles you’re right in the middle of wilderness. You can see condors flying overhead.”

“If Southern California is your Inferno, then Archer is certainly your Dante, or Virgil.”

Millar fixed on a point above the reporter’s head and fell to musing.

“The essential problem,” he said finally, “is how you are going to maintain values, and express values in your actions, when the values aren’t there in the society around you, as they are in traditional societies. In a sense, you have to make yourself up as you go along.

“Archer, I think, is not a hero in the traditional sense, he doesn’t rush in there and save the values. But what he does is a lot better than if the detective, in the name of virtue, goes around knocking people off. That, by many people, is taken as an indication of powerful virtue on the part of the character. The idea of knocking people off is just about the most popular idea in modern American life. But I’m agin it.”

“Well,” said the reporter, “there isn’t anybody in your books who deserves to be knocked off. There aren’t any hiss-and-boo villains.”

“The hiss-and-boo villain died in the nineteenth century,” Millar said. “You know who killed him?” Pause. “Ibsen blamed everybody.”