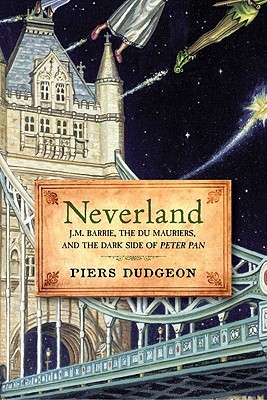

Neverland: J.M. Barrie, the Du Mauriers, and the Dark Side of Peter Pan by Piers Dudgeon ~ 2009. Originally published as Captivated: J.M. Barrie, the du Mauriers and the dark side of Neverland in Great Britain, Chatto and Windus, 2008. This edition: Pegasus Books, 2009. Hardcover. ISBN: 333 pages.

Neverland: J.M. Barrie, the Du Mauriers, and the Dark Side of Peter Pan by Piers Dudgeon ~ 2009. Originally published as Captivated: J.M. Barrie, the du Mauriers and the dark side of Neverland in Great Britain, Chatto and Windus, 2008. This edition: Pegasus Books, 2009. Hardcover. ISBN: 333 pages.

My rating: This is tough. I think 4.5/10. It certainly held my interest, but I have some issues with how the author presented some of his more far-fetched speculations as fact, without any of the language needed to make it clear that some conclusions were very much fabricated by the biographer. Not “good science”, if you get my meaning. Extra points for the vast amount of research that obviously went into this project. Points off for the blatant speculation, sometimes admitted to by the author, that makes “truth” out of shreds of fact.

*****

This was a recent library loan, picked up on a whim because of the du Maurier reference. I hadn’t realized there was any sort of connection, so was quite intrigued by the subtitle. And oh my gosh – what a can of worms this turned out to be.

It’s on the library stack for return today, so this will be a very brief summary.

In short, the author, Piers Dudgeon, has detailed the secret (or maybe not so secret?) obsession by the esteemed and exceedingly successful J.M. Barrie for the family of Arthur Llewelyn Davies and his wife, the former Sylvia du Maurier, and especially their five sons: George, John, Peter, Michael, and Nicholas. Whether the attraction was merely that of fascination for a vibrant and beautiful family, or whether the eventual focus on the five young boys was more sinister in nature, there was a decidedly – how shall I put it? – “focussed” situation going on there. After Arthur’s death of cancer in 1907, Sylvia leaned heavily on the family friend Barrie; her own tragic death three years later left the five children, then aged approximately from seven to seventeen, under the guardianship of Barrie, who, as “Uncle Jimmy”, became even closer in the pre-existing relationship to something of a foster-father.

All of this is clearly documented and not particularly newsworthy, but Dudgeon goes deeply into speculation and conjecture here about Barrie’s infatuation with the Llewelyn Davies family and the du Mauriers. Aside from the predictable insinuations about pedophiliac tendencies in Barrie, something that I was aware of, having read numerous references over the years to his infatuation with the real-life model(s) of his never-aging creation Peter Pan, Dudgeon goes even further into the murky psychological waters, claiming a sort of extra-sensory perception and an ability for “ill-wishing” that spelled doom to anyone upon whom Barrie became fixated. Dudgeon openly implies that Barrie had a hand in the deaths of Arthur and Sylvia L-D, as well as in the suicide of one of the boys as a young man, the death in action of another in World War I, and the suicide of a third as a middle-aged man.

Dudgeon goes out even further on his shaky limb and seems to claim that Daphne du Maurier in particular was deeply influenced by Barrie’s role in her life, and that her books reflect his deep (claimed by Dudgeon) importance in her world. Barrie did indeed come into (occasional) quite close contact with Daphne in her younger years, but I feel that Dudgeon has strongly overstated his influence, seeking to justify his own obsession with the “demonization” of Barrie.

I can easily believe Barrie was a man of morbid and unhealthy obsessions, though the muted accusation of pedophilia has been emphatically denied by the very people who should know, the Llewelyn Davies sons themselves.

All in all, a rather disturbing read, in more ways than one. I’m not sure how reliable Piers Dudgeon’s conclusions are, though much of his research is quite fascinating when viewed with a disinterested eye. I certainly can’t recommend this book as the definitive account of Barrie and the Llewelyn Davies family, and definitely not as a Daphne du Maurier reference – I felt this was the most contrived part of the whole production. All I can say is that if you’re interested (and it is interesting to speculate and delve into Barrie’s dark world, behind the glitter of the stage productions) you should perhaps look into some more reviews – lots to choose from out in the cyberworld – to get a clear idea of Dudgeon’s own infatuation with his theory, and then read away with an open mind.

A good place to start is here, the New York Times book review by Janet Maslin from October 25, 2009.