Jeannie and the Gentle Giants by Luanne Armstrong ~ 2002. This edition: Ronsdale Press, 2002. Softcover. ISBN: 0-921870-91-4. 150 pages.

Jeannie and the Gentle Giants by Luanne Armstrong ~ 2002. This edition: Ronsdale Press, 2002. Softcover. ISBN: 0-921870-91-4. 150 pages.

My rating: 4/10. A completely typical “problem novel” (single parenthood, mental illness, foster children) packed with contrived situations. An eleven-year-old heroine is placed in foster care after her mother has a mental breakdown.

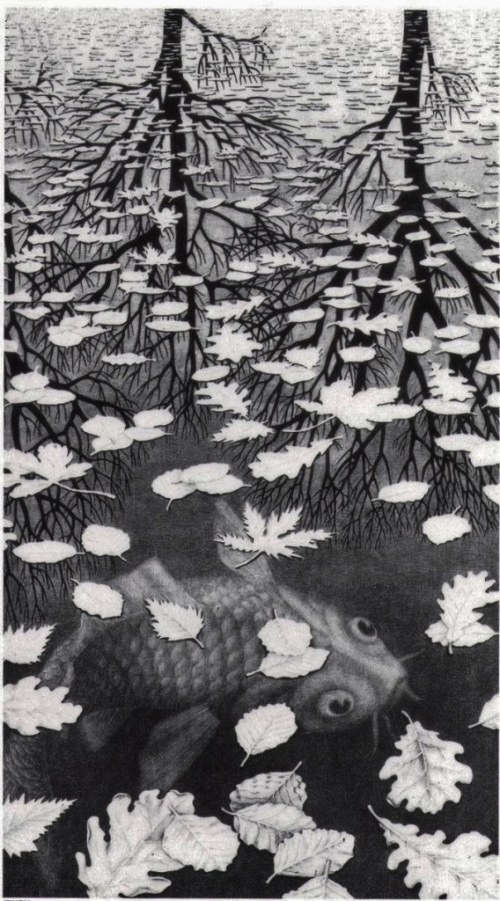

Sadly this one didn’t quite fly. The horse bits were good – the best part of this novel, in my opinion – but they couldn’t salvage the rest of the completely predictable, cookie cutter story. Despite the favorable back cover blurb by my up-the-hill neighbour, poet, writer, and horse-logger Lorne Dufour (aha! now here’s an interesting Canadian Reading Challenge author) it just didn’t click with anyone here. Too bad. Jeannie is set in Kelowna, B.C., and as a home-province, B.C. Interior-set youth novel I really wanted to love it. (Plus the cover image is fantastic.)

From the publisher’s website:

Jeannie and the Gentle Giants, a novel for readers eight to fourteen, deals with the problems experienced by children when they are taken from their parents and have to make a new life with foster parents in a new community. In Jeannie’s case, the problems begin when her mother falls ill and can no longer care for her. Taken from her home, placed with foster parents and unable to discover the whereabouts of her ill mother, young Jeannie withdraws into herself and can think only of running away.

Gradually her defences are breached by two immensely large and wonderful workhorses and their perceptive and humorous owner. Through the horses and her work on the farm, Jeannie develops new interests, learns to ride and becomes involved in the daily life of the farm, even helping with horse-logging. In turn, Jeannie learns about friendship, love and trust, and ultimately gains the maturity and self-confidence to accept the challenge of becoming herself a care-giver. In this sensitive and moving story, Luanne Armstrong draws us into a world of pain, growth and fulfilment.

Lorne Dufour’s back cover blurb:

In this story, the Gentle Giants slowly walk right through our hearts. We will forever remember their presence in Jeannie’s life and that the great Gentle Giants never forget.

~ Lorne Dufour, horse-logger & award-winning author

The author attempted an ambitious level of complexity here, by involving her young protagonist in a rather tangled combination of situations. We have: mentally ill mother, single-parent family with no father in sight, poverty, social stigma as child of mentally ill mother (handled quite well by author in providing heroine with staunch friends who immediately speak up in her favour to school bullies), foster parents who can’t have children, neighbour couple who find they are expecting a baby mid-way through book, heroine’s questioning as to what a family actually is and her conflicting desires to both be with her mother back in the city and to stay in her new, more fulfilling and interesting country life, doctors refusing to allow child to see ill mother – (this didn’t ring true – felt like a plot element to increase tension – mother was experiencing a psychotic episode, some mention of bipolar disorder/manic depression, but once the mother was capable of sending the first letters, why the heck WOULDN”T she be able to have visits from her daughter – wouldn’t that by emotionally beneficial to BOTH of them) – okay, moving on – learning to handle work horses, learning to ride, dealing with an injured horse all by herself, finding a lost child, guilt guilt guilt because heroine feels she has been the cause of the child being lost, feral stray dog tamed and made into pet … My goodness, what a busy, busy girl.

As I said earlier, I really wanted to like this book, but it just didn’t ever feel “real”. Too much was chucked into the mix, Jeannie’s reactions were not very well portrayed – we were continually given the same set of outward clues that she was all bummed out – she had a “shy look”, “looked down”, “blinked to hold back tears”. The language throughout is overly simplistic, as if keeping it accessible to “poor readers” was a major goal.

Does this seem too critical? I feel like a big old meanie for picking this one apart, but, in all honesty, these were my thoughts as I read.

For the record, I really don’t care for “problem books”, for readers of any age, but in particular for young readers. “This is a book about DIVORCE! MENTAL ILLNESS! CEREBRAL PALSY! DOWN’S SYNDROME! BULLYING! ANOREXIA! ETHNICITY! PREJUDICE! BEING GAY! blah blah blah… If you, dear person/dear young child with a similar issue in your life, will only read this book you will feel so much better because you will see how this marvelous hero/heroine dealt with it in their fictional world and you won’t feel so alone.”

Dear youth authors: Write a STORY first. If there are side issues, so be it, for if naturally included those always interest, verisimilitude and richness to the mix. But don’t pick an “issue” and write a prescriptive “here’s how to deal with it, dear” contrived moral tale. Kids aren’t stupid. They don’t need to be told what to think in such a poorly written way. Yes, definitely acknowledge and include the issues, but don’t build a weak story around them, for the sake of marketing the book to the school library network! This whole “issue story” genre encourages sub-par story-telling.

In my opinion.

Jeannie and the Gentle Giants pushed a lot of my buttons, and not in a good way.

Rant over. (For today!)

Oh, hang on – not quite. “Foster” parents – I always thought that foster parents were those filling a long-term role in a child’s life. Jeannie is in what I would classify as “temporary care”, so the immediate (within days) placement of Jeannie with a new, albeit temporary, “mom” and “dad” didn’t ring true. It is continuously stated that Jeannie will be reunited with her mother once the doctors get her (mother’s) meds figured out. I mean, the actual family placement is okay, but the whole “this is your new family” thing felt rushed and phony. No wonder the poor kid is a basket case – “Here, Jeannie, meet your new mom!”

And another quibble, this with the publisher’s website and back cover plot outline. It sounds as though Jeannie doesn’t know where her mother is through all of this. She’s in the flipping hospital in Kelowna, people. Did you not read the book?! Jeannie knows this, her social worker knows this, her “foster parents” know this – they make continual phone calls and Jeannie’s mom writes her letters, for crying out loud! So why is this presented in the promotional material as “child torn away from parent and searching for her”? The kid tries running away to go see her mother, but she knows where her mother is. She’s turned away as she tries to buy a bus ticket to Kelowna, to go to the hospital, to see her mother, because Jeannie knows she’s there.

Okay, now I’ll quit. I’d hesitated to review this book, because it let me down so sadly, but I did say I’d review and post every Canadian book I read, so here goes. There are a few more disappointing titles lined up for review, so a heads-up for those wondering why I’m so crabby today. I’ve just been pushing them back in the queue, but have decided to tick them off my deal-with list before 2013 hits.