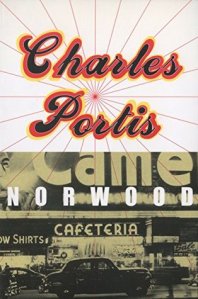

Norwood by Charles Portis ~ 1966. This edition: The Overlook Press, 1999. Softcover. 168 pages.

Trigger warning. I think I need to put this out there in a prominent place – this book has era-expected language, meaning in this case that you will come right up against the n-word, multiple times. It’s generally used in a derogatory way by a key character – not our eponymous protagonist, which was a great relief to me – but one of the unsavories he comes in close contact with.

Reading with 2022 eyes, I have to say I stopped dead when I hit the first occurrence, and thought exceedingly hard about where we’ve come with our current hyper-sensitivity to problematic language.

Which I think is one of the main reasons why we shouldn’t ban or censor books from a time before – we should feel repugnance and we should take time to consider how and why our personal and societal attitudes have changed.

And this is all I will say about that, because I am well aware that opinions on tolerance of and censorship of currently unacceptable language in writings from a prior era will differ. Every reader of vintage fiction is going to have this conversation with themself as things pop up.

If you’re still wanting to stay with me on this one, let’s take a look at this book, this weird and rather fantastic (in every sense of the word) road trip tale. It’s kind of like a stream-of-consciousness fever dream, and it’s brilliant.

If you’re still wanting to stay with me on this one, let’s take a look at this book, this weird and rather fantastic (in every sense of the word) road trip tale. It’s kind of like a stream-of-consciousness fever dream, and it’s brilliant.

Norwood Pratt, just back from Korea, is now an ex-Marine. He’s also now an orphan – his mother is dead, his father has just died – and the feeling back home in Norwood’s current home town (the family’s moved around a lot) of Ralph, Texas is that Norwood needs to come on back home and look after his sister Vernell. She’s taking things hard, and she never really was that viable a specimen even before the latest bereavement, so there’s nothing for it but that Norwood take a hardship discharge and get back into civilian life.

Norwood is on the bus heading back to Texas from Camp Pendleton in California when he realizes that he’s forgotten to collect a debt owed him by one of his Marine buddies. It’s $70, not exactly a fortune, but it’s the principle of the thing, thinks Norwell, and he decides to settle down for a prolonged sulk as the bus rolls eastward.

The sulk doesn’t last long, as Norwood almost immediately befriends a young couple with a baby, transient vegetable pickers heading back to Texas with their California asparagus-season money. He invites them to come and stay for a few days, and our story is on.

Sometime during the night the Remleys decamped, taking with them a television set and a 16-gauge Ithaca Featherweight and two towels. No one could say how they got out of town with all that gear, least of all the night marshal. The day marshal came by and looked at the place where the television set had been. He made notes.

If Norwood has a weakness, it might be that he’s sometimes too trusting. But as subsequent occurrences go to show, he’s far from naive.

Back to his old job at the Nipper Independent Oil Co. Servicenter, Norwood settles down to looking after his still-depressed sister and doing all the cooking and housekeeping.

Sometimes he sat on the back steps wearing a black hat with a Fort Worth crease and played his guitar – just three or four chords really – and sang “Always Late – With Your Kisses,” with his voice breaking like Lefty Frizzell, and “China Doll” like Slim Whitman, whose upper range is hard to match. The guitar wasn’t much. It was a cheap West German model with nylon strings he had bought at the PX. He also put in a lot of time on his car. He had bought a 1947 Fleetline Chevrolet with dirt dobber nests in the heater and radio for fifty dollars. He put in some rings and ground the valves and got it in fair running shape. He loosened the tappets and put up with the noise so as to keep Vernell – who would race a motor – from burning the valves. She burned a connecting rod instead.

Norwood is good hearted and patient, and a darned good brother, but life feels flat to him.

One night he came home from work and said, “I’m tard of working at that station, Vernell.”

“What’s wrong, bubba?”

“Every time you grease a truck stuff falls in your eyes and your hair and down your back. You got it pretty easy yourself yourself. You know that?”

“Why don’t you get a hat?”

“I got plenty of hats, Vernell. I don’t need any more hats. If all I needed was another hat I would be well off.”

“What do you want to do?”

“I want to get on the Louisiana Hayride.”

Yes, Norwood has a secret longing to be a country and western singer, and the prospects are darned poor for that, and he’s starting to get depressed and even a little bit angry. Brooding away about the injustices piling up in his life, he decides to hunt down the debt owed to him by his old army buddy.

So Norwood leaves Ralph, driving an Olds 98 and hitch-pulling a Pontiac Catalina, both gleaming with fresh new paint. He has a commission from one Grady Fring (“the Kredit King”) to deliver the cars (and an unexpected passenger) to New York and return with another car, his payoff a chance to see the country and $50 in driving fees. Works out good, thinks Norwood, for he has a line on his army buddy who him the $70 – the guy was last heard from in New York. Win-win.

Well, things immediately go sideways, and inside out, and upside down. You have to read this yourself to find out all the many details, but I will tell you that during his travels, Norwood hops a freight train, meets a lot of interesting people, including Mr. Peanut, and the world’s smallest perfect fat man. and a beatnik girl who reads him passages from Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet but doesn’t commit herself so far as to go to bed with Norwood, which leaves him mildly disappointed but he gets over it. Along the way he loses his precious cowboy boots – thirty-eight dollars, coal-black 14-inchers with steel shanks and low walking heels, red butterflies inset on the insteps – and he never gets on the Hayride, but he gains a few things, too. Including a college-educated chicken and a lady-love. Could be worse.

I will leave you with one of my favourite snippets from this goofy little book. Here’s Norwood in New York, contemplating tattoos.

There was a tattoo parlor and Norwood looked at the dusty samples in the window. He had a $32.50 black panther rampant on his left shoulder, teeth bared and making little red claw marks on his arm. He had never been happy with it. Something about the eyes, they were not fully open, and the big jungle cat seemed to be yawning instead of snarling. Norwood complained at the time and the tattoo man in San Diego said it wouldn’t look that way after it had scabbed over and healed. Once in Korea he sat down with some matches and a pin and tried to fix the eyes but only made them worse. Many times he wished that he had gotten a small globe and anchor with a serpentine banner under it saying U.S. Marines – First to Fight. To have more than one tattoo was foolishness.

Norwood knows what he thinks.

This was Charles Portis’s first published novel, and it was very well received. Very much a product of its free-wheeling time – and one has to wonder if Mr. Portis was indulging in something illicitly mood-enhancing when he rattled this one off, but it comes together just right, in a we’re just along for the ride sort of way.

I feel like Norwood is very much a dress rehearsal for 1976’s much longer, more complex, but pleasingly similar The Dog of the South, one of my personal secret treasure books.

Now, your own mileage may vary on Charles Portis. My husband, who shares many but not all of my reading tastes, isn’t a huge fan of either Norwood or The Dog of the South, though he laughs along with me at some of the absolutely deadpan humour. Portis can sure nail inner thoughts and dialogue.

No, he (my husband) is something of a traditionalist – he much prefers Portis’s most well-known and likely most popular book, True Grit. (Yes, this is that Charles Portis.)

Me – I like ’em all. Too bad there are so few. Five novels. Not nearly enough.

My rating: 9/10. It would be a 10, but it’s just too short. So many questions left unanswered!

For the record, this novel was made into a 1970 movie starring Glen Campbell as Norwood. Major liberties were apparently taken to Hollywood-ize it – very likely so Campbell could showcase his musical chops. (He also played and sang on the soundtrack.) Full disclosure: I just watched the first ten minutes of this on YouTube. It was…regrettable. Please read the book first. Or better yet, instead of. (Sorry, Glenn.)

Read Full Post »