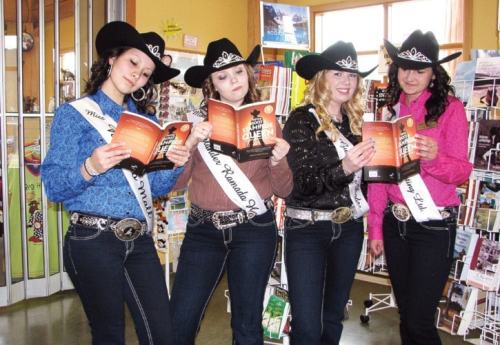

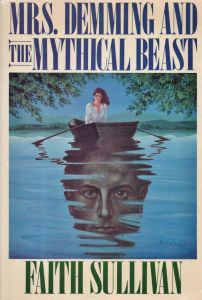

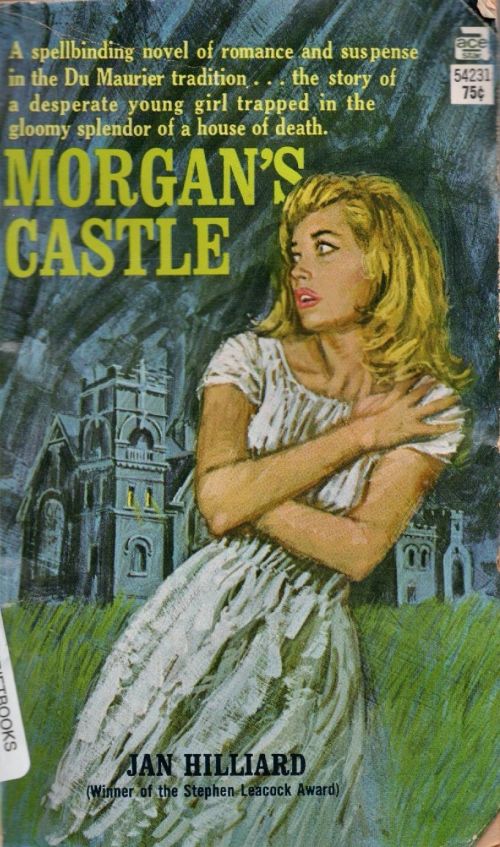

Mrs. Demming and the Mythical Beast by Faith Sullivan ~ 1985. This edition: Macmillan, 1985. Hardcover. 341 pages. ISBN: 0-02-615450-1

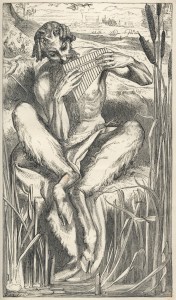

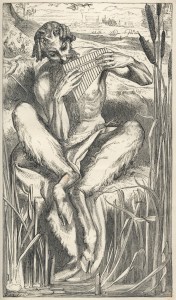

What was he doing, the great god Pan,

What was he doing, the great god Pan,

Down in the reeds by the river?

Spreading ruin and scattering ban,

Splashing and paddling with hoofs of a goat,

And breaking the golden lilies afloat

With the dragon-fly on the river…

From ‘A Musical Instrument’ by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

It’s my second time round tackling this somewhat wacky concoction by Minnesota writer Faith Sullivan. The first time round I abandoned it early on, before page 22 for sure, because I certainly would have remembered the erotic dream sequence between Larissa and her (so far) platonic (and also married) arms-length lover Harry, if I’d gotten that far along.

This book was recommended to me by a fellow book blogger whose name utterly escapes me – apologies to whoever that was – and I have to thank them for that lead, because this is how we discover hidden gems.

For some readers, this would be that. For me, not so much, though it was a great opportunity for mulling over where the various hits and misses were, always a very individualized response.

Here’s the blurb from Publisher’s Weekly, November 4, 1985:

Larissa [the titular Mrs. Demming] is approaching 50, her children are grown and marrying, her preoccupied husband, Bart, is engrossed in writing a book that threatens to take over his life. For her part, Larissa paints, reads, muses, rows across the river near their Minnesota cottage and picnics on the shore, murder mystery in hand. Until, one day, she looks into the woods and sees a pair of eyes staring back at her. They are the eyes of Pan, an ageless Greek satyr who has been living there since a lovesick Victorian lady brought him to America. Larissa and her Beast discover many affinities, including the satisfaction of sexual passion. Meanwhile, however, Larissa’s domestic life becomes chaotic: a daughter turns hostile; Larissa’s elusive father shows up; a grandchild is born; a love affair with an old friend seems inevitable; a developer threatens the family’s bucolic serenity. Escaping to Greece with her satyr, Larissa confronts the beast within and returns to take up life’s real dramas. Related in a witty, distinctive style and marked by subtle insights, the novel is a pleasure, although occasionally the plot seems contrived. Sullivan also wrote Watchdog and Repent, Larry Merkel.

The thing I liked most about this book was the conceit of a transplanted Olympian god – Pan himself! – who finds himself in exile in the New World, dallying with a series of Minnesota mortals, the latest of whom is our protagonist. How did Pan get to America, why is he stalking Mrs. Demming, and, most intriguing to my mind, though never addressed by Faith Sullivan, what the heck is happening back in the Old Country without his Pan-ic supervision of the Grecian woods?

The thing I liked most about this book was the conceit of a transplanted Olympian god – Pan himself! – who finds himself in exile in the New World, dallying with a series of Minnesota mortals, the latest of whom is our protagonist. How did Pan get to America, why is he stalking Mrs. Demming, and, most intriguing to my mind, though never addressed by Faith Sullivan, what the heck is happening back in the Old Country without his Pan-ic supervision of the Grecian woods?

Sullivan tiptoes around most of these queries – though she eventually gives more detail – and keeps re-routing things back to an oddly undeveloped plot based on the threat of a condominium development four miles upstream of bucolic Belleville, a fictional Minnesota town located on the banks of Belle Riviere River, as the locals insist on redundantly calling it, much to the secret annoyance of Larissa, who has some strong opinions, mostly kept well hidden and unvoiced.

Larissa is in a state of internal ferment these days, mostly to do with her daughter Minerva’s upcoming marriage. Minerva, in her twenties and a successful and rising investment banker in the Demming family’s hometown of Minneapolis, just an hour or so away from the Belle Riviere summer cottage where the main action of the novel occurs, is set to wed an absolutely suitable and upright attorney.

Larissa thinks this is a huge mistake, and has made the critical error of voicing this to Miranda. Not that she objects to the young man regarding his husbandly suitability. It’s just that Miranda is living such a safe and organized life, while her mother, projecting wildly, thinks that her beloved daughter should engage in a year or two of bohemian living (meaning sexual flings, preferably abroad in some more exotic location than staid old Minneapolis) before she settles down.

Miranda disagrees. Strongly. And I found myself rather on her side, though I’m not quite sure if the author had that in mind.

This is a very busy book, and Sullivan throws a lot of things into the mix. It often feels like she loses track of some of her plot strands; they lay about all over the place, tripping up the reader as trot along madly in Larissa’s increasingly frenetic wake, murmuring, ‘Who?! What?! Where?! When?! WHY?!”

Beautifully written in places, not so much in others. Plot twists which fell very flat for me included a well telegraphed “surprise” denouement regarding Larissa’s relationship with her widowed Irish-American father Jamie. (Let’s just say they were very, very close during Larissa’s teen years, after her mother tragically died.) And there was the sacrifice of one of the novel’s most sympathetic characters to what I felt was an unfair demise. And a convenient solving of Larissa’s own too-staid-and-safe marriage issue, which I felt rather too contrived even for this very obvious fiction. And did I mention the cringe-inducing sex scenes? Including a loving description of Pan’s manly bits highlighted by the silky white curls of his goat legs. Ack! Too much, too much!

So, that goat-footed god thing. He’s quite obviously symbolically introduced into the mix to give Larissa the impetus to get her inner life sorted out, but he’s also presented as a very real entity, with the problems that come along with that, such as his transportation both to and from America, a century or so apart, using normal forms of public transit. Spoiler: Baggy pants and a wheelchair factor into this. Luckily no one is moved to pat down the handsome Greek guy at the airport on his repatriation journey…

My rating: 6/10. It did keep me engaged, once I committed to the story and made a conscious decision to disregard plot flaws, and to fast forward through the sexy bits, which I found embarrassing, on the writer’s behalf as much as the reader’s. Consider yourself forewarned.

Internet reviews are very sparse for Mrs. Demming and the Mythical Beast, though “cult classic” and “horror” pop up several times. I’m not sure about that first label, but the second is incorrect. No horror here. If this were published today, cleaned up a bit to rid it of its very occasional, era-expected political incorrectness, it would probably win accolades in certain circles, and get passed around with the bottle of red wine at evening book clubs patronized by those who don’t take these things too seriously.

Mrs. Demming appears to be out-of-print, though it went through several print editions, in hardcover and paperback, and is readily available second hand, and on Kindle.

Faith Sullivan went on to write a number of other novels, all set in Minnesota, and all reportedly well received. I have not read any of them, but would be happy to do so if they came into my orbit.

FAITH SULLIVAN – Biography and Bibliography from Encycopedia.com

Read Full Post »

The thing I liked most about this book was the conceit of a transplanted Olympian god – Pan himself! – who finds himself in exile in the New World, dallying with a series of Minnesota mortals, the latest of whom is our protagonist. How did Pan get to America, why is he stalking Mrs. Demming, and, most intriguing to my mind, though never addressed by Faith Sullivan, what the heck is happening back in the Old Country without his Pan-ic supervision of the Grecian woods?

The thing I liked most about this book was the conceit of a transplanted Olympian god – Pan himself! – who finds himself in exile in the New World, dallying with a series of Minnesota mortals, the latest of whom is our protagonist. How did Pan get to America, why is he stalking Mrs. Demming, and, most intriguing to my mind, though never addressed by Faith Sullivan, what the heck is happening back in the Old Country without his Pan-ic supervision of the Grecian woods? I grew up rural, in the central Cariboo-Chilcotin region of British Columbia, and Williams Lake was “town”, location of schools, shops, restaurants, public library and movie theatre, not to mention an impressive array of both churches and drinking establishments.

I grew up rural, in the central Cariboo-Chilcotin region of British Columbia, and Williams Lake was “town”, location of schools, shops, restaurants, public library and movie theatre, not to mention an impressive array of both churches and drinking establishments.